The University as Feudal State: The Abysmal Failure of Interdisciplinarity in Higher Education

by Doug Mann

1. Overture

Knowledge

and research within the modern university has a curiously feudal character,

given its division into a series of faculties and departments each with their

own pedagogical self-definitions. By its very structure, which is specialized

and hierarchical, the modern university is hostile to inter-disciplinary

teaching and research. Interdisciplinarity flies

directly in the face of the corporatist nature of the modern university, which

divides knowledge and money into a discrete number of internal corporate

bodies. We can no more expect our universities to be interdisciplinary than we

can expect monkeys to speak French or cats to sing Wagnerian operas: it’s

simply not in their nature.

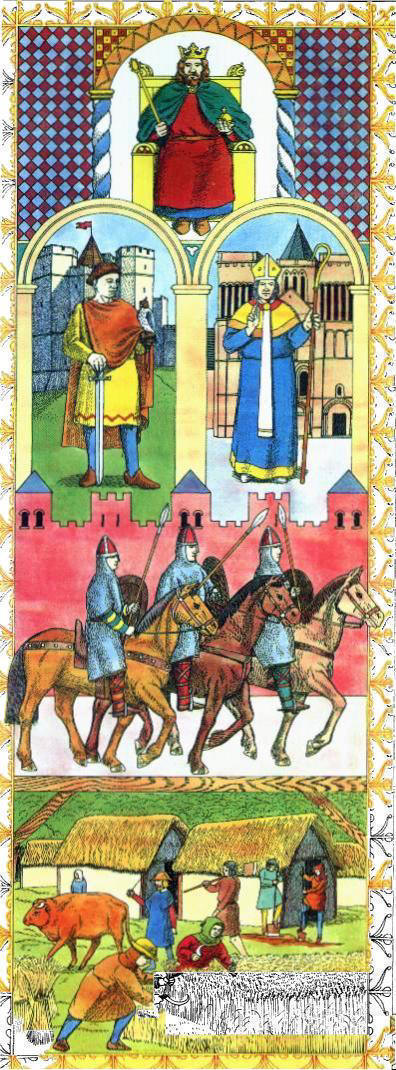

2. The University as

Feudal Hierarchy

Both

the feudal state and the modern university share the basic characteristics of

being hierarchies held together by power structures, flows of resources and the

fealty of the lower orders to those above them. Just as the feudal kingdom was

divided into a myriad of fiefdoms of various sizes, the university is divided

into “grand faculties” such as the Arts, Social Sciences and Sciences, within

which we find individual departments such as Philosophy, Sociology and

Chemistry. Although some laws and regulations apply throughout the entire

feudal kingdom (or modern university), many such laws are local in character,

varying from fiefdom to fiefdom (or department to department). The local

fiefdom is the real site of important decision making.

At

the top of the feudal state was the King, who had little influence on “local”

affairs, and relied on the great lords of the land to collect his taxes and

defend his realm. The obvious parallel in universities is the President, the

public face of the school, who is never seen in individual classrooms, and is a

stranger to almost all the “lower orders” (more on them in a while). Checking

the King’s power were the Pope and his bishops, paralleled in modern

universities by the upper echelons of administrators. Beneath them a vast army

of priests ministered to the spiritual needs of their flocks, just as a vast

army of administrators and support staff minister to the technical and

bureaucratic needs of the modern university.

Over

each of the larger feudal fiefdoms, e.g.

In

the town lived artisans, their equivalent at the university being graduate

students who spin their intellectual wheels marking papers and writing theses

just as the medieval potter spun clay on his wheel. At the bottom of the feudal

hierarchy were the peasants, who toiled on the land and provided taxes to the

lords. We have our own peasants, the undergraduate students, who fund the

system with their tuition and their parents’ taxes. The parallel is uncannily

precise.

3. Specialization in

Graduate Education and Hiring

Interdisciplinary

teaching and research is impossible without interdisciplinary scholars, yet the

feudal nature of the modern university actively discourages the hiring and

promotion of such scholars.

For

example, in the discipline whose hiring practices I know best, Philosophy, most

jobs require (a) a doctorate specifically in Philosophy, with those from

“major” American universities such as Harvard, Yale and UCLA having favoured status, and (b) a specialization in a subfield of

Philosophy such as Ethics, Philosophy of Mind, or Logic with some graduate work

and perhaps teaching experience to back this claim on specialisation

up. This pattern of “Major Discipline/Secondary Specialization” applies to the

vast majority of academic hirings in modern

university departments.

I

conclude from my own tales of Chaucerian woe in pursuing a tenure-track job in

several distinct disciplines that at least four “iron laws” apply to academic

hiring, all of which favour feudal specialization and

strongly oppose the hiring of interdisciplinary scholars:

! 1.

Discipline: Almost all permanent positions require a Ph.D. in the specific

discipline associated with the department doing the hiring: e.g. people with

Sociology Ph.D.s don’t get jobs in Political Science departments, even if they

know a lot about political science.

! 2.

Specialization: Second, most tenure-track jobs require some sort of specific

specialization within that

discipline, sometimes defined so narrowly as to exclude the great majority of

those with Ph.D.s in that discipline. This specialization trumps both general

teaching experience and non-specialized publication lists.

! 3.

Publications: A published book and 20 articles within a given discipline outside of the specialization a job ad

calls for are worth less than a couple of forthcoming articles and graduate

work within that specialization. Two

or more books and a long list of articles and substantial teaching experience

in discipline A are worth preciously nothing in discipline B, even if these two disciplines are

intellectually related, e.g. Sociology and Political Science. Work simply

doesn’t count unless it’s work within the “feudal

fiefdom” associated with the job description. Formal university credentials are

like noble titles: each entitle one to unique

privileges within a given fiefdom, yet to little more than deference outside

one’s fiefdom.

! 4. Logic of

Hiring: Because of the discipline-and-specialization system of hiring and the

feudal structure of the university, even a well published interdisciplinary

scholar with substantial teaching experience and a genuine interest in a

variety of subjects won’t get hired into a permanent position. Such a scholar

is almost always automatically rejected by hiring committees. I know from

personal experience that some disciplines even look down on interdisciplinary

publication and teaching as a sign of weakness, an inability to “make up one’s

mind,” to being a dilettante. This logic of hiring tied in well with our larger

techno-bureaucratic society, which favours widget

adjusters over deep thinkers.

These

iron laws are very effective at weeding out interdisciplinary scholars from

achieving success in the modern university. Specialisation

is the name of the game.

4. Specialists and

Generalists: A Fallacy Corrected

Underlying

the logic of feudal specialism in university hiring and structure is a basic

fallacy about how we learn new things, and how we apply this knowledge to

research and teaching. Scholars learn by reading books and articles, by doing

surveys and experiments, or in some disciplines by listening to music or

watching video. Certainly graduate students do these things. But post-graduate

teachers also do these things,

especially if they’re contract or adjunct professors shuffling from one new

course to another. Anyone with very basic research skills, time and willpower

can educate themselves about a specialization within a field if they already

have some vague familiarity with it.

Teaching

a new course in an area one is only loosely familiar with is like taking a

graduate seminar or two in the area, with one major addition: the teacher is

expected to do twenty or more hours of presentations to his or her students,

the graduate student (generally speaking) only one or two. I remember a couple

of years ago preparing to teach my Comic Book Culture course for the first

time: over the course of a year or so I went from being having a strong amateur

interest in comics to being as much of an expert in the field as all but a

handful of people in Canadian universities.

My

point isn’t to establish pedagogical bragging rights over the X-Men or Frank

Miller’s Dark Knight, but to make clear the obvious fact that teaching a course

in a new field compels one to do some serious research in that field. Further,

writing a series of articles or a book in a new field has the same effect.[1]

There’s nothing magical about graduate work that qualifies one for a job in a

given specialization: learning should be a life-long process for all

professors, and most certainly is for interdisciplinary scholars. The brain

isn’t a static organ cryogenically frozen on the day of one’s graduation, and

education isn’t limited to a few years of structured study, ending a year after

one collects one’s doctoral diploma: to think otherwise is to wallow in a naive

credentialism.

What

is a specialist? Someone who knows a lot about a single field

of knowledge, but not very much about anything else. What is a

generalist? Someone who has a significant degree of knowledge in several allied

fields, and bits of knowledge about many other things. The problem with

specialists is that they don’t have the knowledge base to apply

extra-disciplinary ideas to their writing and teaching. Yet in most cases the

specialist is asked to teach undergraduate courses outside their specialization

strictly defined, a task for which they’re ill suited. And besides, one doesn’t

have to be a specialist to teach effectively most undergraduate courses in a

given discipline: one just has to know where

to get the knowledge needed to fill in the gaps between the things one

already knows and the willingness to do so.

A

humanistic view of education tells us that a knowledge

of the classics, languages, history, politics, philosophy, film, art and music

can inform and enliven a discussion of pretty well any field of study outside

of highly technical or scientific disciplines. Students’ education is enriched

by teachers who can bring in events from history, philosophical ideas,

cinematic metaphors, or literary allusions, amongst other things. Yet

universities don’t care about such general knowledge when it comes to hiring:

they chose the narrow specialist over the more well-rounded

generalist in almost all cases.

Knowledge

isn’t naturally divided into specializations: this requires an act of will on

the part of educational bureaucracies, as all good Foucauldians

know. The way that the current menu of disciplines have developed into islands

of knowledge in the modern university, each with is own canon of great works,

is the story of accidents, missed opportunities, and arbitrary decisions. If we

look at my own university, the

This

division of labour makes no sense intellectually:

it’s the result of bureaucratic struggles, not logical thinking. This makes

even less sense when we remember that films are made specifically for TV, while TV networks broadcast

films to entertain the masses. Like Hegel’s cats, in the night all disciplinary

boundaries are grey.

Harold

Innis, Marshall McLuhan and George Grant, important

Canadian philosophers of media and culture, are

discussed in only a handful of Canadian Philosophy departments, yet are widely

taught in Communications departments.

This doesn’t make sense either. The fact that Media Studies and

Communications programs even exist in the first place speaks to fear and

loathing felt by philosophers, sociologists, and literary scholars of a

generation ago toward the study of mass media and popular culture. They didn’t want to get their hands dirty

with the study of popular media, so they left this to the newly established

communications departments.

I’ve

taught Marxism in Philosophy, Sociology, Political Science and Media Studies

programs, supposedly distinct disciplines, yet haven’t observed any changes in

the basic tenets of Messieurs Marx and Engels as I move from one discipline to

another. The way that knowledge is divided up between university disciplines is

akin to the way that land was divided between feudal fiefdoms: in some cases

the borders might sensibly follow rivers or mountain ranges, in others they run

arbitrarily through a farmer’s field or across a deserted wasteland. Don’t look

for some deep logical rationale in these divisions.[2]

5. Follow the Money

Universities have a corporatist structure that channels money and other resources through a hierarchical structure to specific faculties and departments. These departments compete against each other for students in order to get more access to these resources. The more students they get, the more money they get (though certain key areas of research, mostly in the natural sciences, are partly immune to this tendency). The division of knowledge into disciplines or specializations each with its own administrative structure, followed by the competition of these structures for students and money, militates against the crossing of disciplinary boundaries. If we follow the money, we’ll find academic corporations competing for resources, justifying that competition by emphasizing the importance of their own intellectual specialty. Such a system cannot foster interdisciplinarity. It’s little wonder that when we scan the lists of permanent faculty in most departments we don’t find any.