The

Rump Parliament of Modern Academic Philosophy

By

Doug Mann

1.

The Problem Delineated

The

way that philosophy is defined in the contemporary English-speaking academy

shows the results of a lengthy process of the systematic shaving off of the

discipline into narrower and narrower fields of study, largely under the

tutelage of twentieth-century analytic philosophy.[1]

Bertrand

Russell actually gives an early account of this process from a benign

perspective in his 1912 book The Problems of Philosophy: once a subfield

becomes a science, it leaves philosophy behind, with psychology being the most

famous case in point of how a field of philosophy becomes a science. I will

argue that Russell’s “sciencization” hypothesis is

explicitly ideological, and simply doesn’t cover all meaningful cases of the

shaving off of philosophy. Instead, the proper way of understanding the history

of this fragmentation is by using a political model, by comparing it to the way

that a dominant faction in a revolutionary state systematically purges its

enemies in order to both protect itself and to exert its control over the

nation.

English-language

academic philosophy is now in a post-purge period of its development, ruled

over not by the iron fist of a Cromwell or the national razor of the Jacobins,

but by the velvet glove of a mass of analytic philosophers committed to a view

of philosophy as a mere shadow of what it once was, a shadow that emphasizes

links to physical science and the logical analysis of philosophical language.

This shadow was not created by a series of logical debates aiming at “truth,”

but by a train of ideological and political struggles aiming at power.

2.

Mapping a Discipline

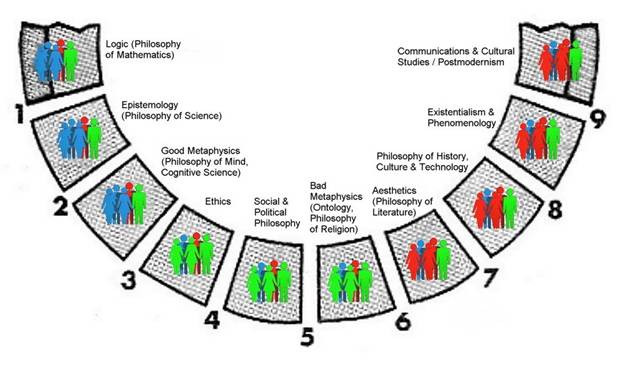

Before moving on to my political model, let’s look at how analytic philosophers themselves map their discipline. An astonishingly clear picture of this map is provided by Ted Honderich in The Oxford Companion to Philosophy (1995), which he edited. In the Appendix to this mini-encyclopaedia Honderich maps the various fields of philosophy as a sort of solar system (see the diagram below).

Diagram One: Honderich’s Map of the Philosophical Solar System

At

the fiery center of this solar system we find exactly what we would expect from

an analytic philosopher: epistemology, logic, and metaphysics. In the first orbit we find fields allied to

the former, namely the philosophies of language, science, and mind, along with

moral philosophy. At the solar system’s outer edge, in the darker regions of

academic space, we find the fields that Honderich

feels are peripheral to the core interests of philosophy: social and political

philosophy, the philosophies of history and law, aesthetics, the philosophies

of education, religion, and mathematics.

Although

admitting that many different maps of philosophy are possible, he justifies his

own map with the odd remark that as we move away from the core area, the other

items tend to be less general, and to be dependent on these core items, while

the core items are not dependent on the peripheries. He concludes that for

these reasons “philosophers have given more attention to the more central

items, so that the diagram also to some extent maps popularity” (p. 928). The

obvious question here is, popularity according to

whom?

Epistemology,

logic and metaphysics are just as dependent on questions of moral, political,

and aesthetic values as the reverse. Firstly, they all take place in

institutions maintained either by the state or by some private interests, and

thus are associated with economic and political values; second, researchers’

choices of which area of research to pursue are also governed by moral and

aesthetic values; third, the sense of the rightness of a solution to a problem

in these areas is as often a reflection of feelings of its goodness or beauty

as its logical or empirical truth. If it weren’t, then there would be a body of

epistemological and metaphysical problems that would have been settled, once

and for all, just as science has given us a series of physical laws that, with

some qualifications, are accepted as true beyond doubt. Yet there are few such

firm conclusions in these fields of philosophy.

And

most fundamentally, we have to ask Honderich and

like-minded thinkers, why is moral philosophy (along with the social and

political philosophies which Honderich sees as its

offshoots) dependent on logic and epistemology, and therefore less fundamental,

than the core areas? This has certainly not been accepted by the majority of

important thinkers in the history of philosophy - many have produced quite coherent

discussions of moral philosophy with little if any reference to these “core

disciplines” (at least directly, in the works where they intend to focus on

morals and politics). Quite the opposite - important thinkers such as Socrates,

Plato, Hobbes, Hume, Mill, Marx, Nietzsche and Sartre, just to mention a few,

seemed to have thought that Honderich’s core fields

are mere propaedeutics to more important moral,

political and aesthetic questions. In short, values zoom in and out of the core

of this solar system like so many errant comets, putting into question the

accuracy of his cosmic map.

A

good test of the arbitrary nature of Hoderich’s map

of the discipline is a visit to the beginnings of the analytic/Continental

split in the eighteenth century. A core thinker here was David Hume. His core

text is, of course, A Treatise of Human Nature, which despite falling

dead born from the presses, presents in its own way a superb map of philosophy

as seen by an early modern empiricist. Hume was no obscure Heidegger or wooly-headed Foucault, but a sound and sober Scot who

believed as earnestly as Ayer in the elimination of philosophical confusions

through the use of good arguments.

For

Hume, the telos of philosophical speculation was

certainly not logic. His one discussion of logic in the Treatise comes

on p. 175 of the Selby-Bigge edition, during a

treatment of causality. In it he ridicules the “scholastic headpieces and

logicians” for showing no superiority over the “vulgar” in their ability to

reason, which gives Hume the determination to avoid “long systems of rules and

precepts”, turning to the “natural principles” of the understanding instead.

Nor

was his central concern epistemology and “hard” metaphysics in isolation,

though these certainly interested him (admittedly, the “soft” metaphysics

surrounding the philosophy of religion occupied his thoughts to a great

degree). Instead it was human nature, whose study he saw as a moral

science. He makes this crystal clear in the Introduction to the Treatise, where

he says that “all sciences have a relation, greater or less, to human nature”

(p. xix), including mathematics and physical science.

The

organization of the book also makes his interest in morals clear. Book I tries

to clear away some epistemological and metaphysical confusions, though even

Hume himself admits not entirely successfully - it ends with a sceptical

concluding section in which he fancies himself a “strange uncouth monster” (p.

264) expelled from all human commerce. He engages in some existential angst

while walking alone the river, then decides that a glass of wine and a game of

backgammon with friends, and not another dose of epistemology, will cure this

angst. Book II is on the psychology of the passions; Book III on moral

philosophy, or what we would call today ethics and political theory, with a few

other things mixed in. This organization is no accident - the Scottish

Enlightenment as a whole saw moral philosophy, and the social life it studied,

as the central preoccupation of philosophy. And to understand social life it

engaged in a diverse series of inquiries that encompassed fields that we would

call today philosophy, history, political science, psychology, sociology,

literary criticism, and economics. In fact, an argument could be made that the

last three fields owe their existence to the explorations of the Scots - Adam

3.

A Historical Analogy: The English and French Revolutions

3.

A Historical Analogy: The English and French Revolutions

In

most major revolutions, from the English Civil War of the 1640s to the Russian

Revolution of 1917 to the decline and fall of the Soviet empire, a central

party (or leader) has systematically eliminated opposition groups that it sees

as threatening its power. I take my basic metaphor from the English Civil War

of the 1640s, specifically, from the purge of December 6, 1648 when Colonel

Pride barred or arrested members of the House of Commons who opposed the trial

of King Charles II. Pride’s Purge took place under the orders of Oliver Cromwell, head of the New Model Army and of the Puritan

faction in

Yet

perhaps the classic case of this process is the series of purges in the

National Convention of the

Other

cases come to mind - the struggle for power in 1917-1920 in the post-revolution

Soviet Union between Lenin’s Bolsheviks and their rivals; Stalin’s purges in

the 1920s and 1930; and even the post-1989 politics in some countries in the

former Soviet Empire (Vladimir Putin’s recent manoeuvrings come to mind). In

all cases a strong leader or party systematically eliminated its opponents to

achieve, at least for a time, its political hegemony.

4.

An Outline of the Rump Parliament

The

core of philosophy at present is epistemology, logic and what I shall call

“good” metaphysics, which includes things like the mind/body question and

cognitive science. Allied to these issues is a strong regard for the philosophy

of physical science. These concerns represent the hard rump of the modern

parliament of philosophy, and are pictured in the diagram below as its right

wing.

At

the border of this rump, in the center of the parliament, we find ethics,

applied ethics, social and political philosophy, and “bad” metaphysics i.e. the

philosophy of religion and speculations about the nature of reality as a whole.

These are usually represented in at least a middling way in Philosophy

departments, but for the most part in a spirit that assimilates them to the

concerns and methods of the analytic rump. For example, an analytic philosopher

will typically divide a 12-week Introduction to Philosophy course up in

something like the following manner: 2 weeks on basic logic, 3 weeks on “hard”

metaphysics, 5 on epistemology, and 2 weeks on ethics (with political

philosophy being assimilated to ethics, and aesthetics, the philosophy of

culture, and Continental thought totally ignored).[2]

On

the left side of the old parliament of philosophy, but largely excluded from

the rump, are aesthetics, the philosophy of history, and existentialism and

phenomenology, which are represented in rumpish

philosophy departments in a token fashion, if at all (despite the popularity of

existentialism with students, if it is presented in a coherent and sympathetic

fashion by instructors).

At

the left end of the old parliament are a series of subsidiary theoretical

interests largely foreign to the rump which are

usually totally excluded from it. These include communications theory and

cultural studies, post-structuralism, postmodernism, and the social theory that

comes out of these fields of study. It might also include psychology proper,

although in this case we can assume that Russell is right that its exclusion is

based on its having achieved some sort of “scientific” status.

Diagram Two: The

Parliament of Philosophy

[right wing] [left wing]

The

domination of this logical-epistemological rump is by no means the result of

some process of natural academic selection or of a universal agreement that the

areas of study excluded from it are entirely unworthy of study. Instead, it is

the result of a series of unique historical and political events in academic

life, allied to a series of basic presuppositions and prejudices on the part of

analytic philosophy. Specifically, it is the result of an implicit decision in

much of the Anglo-American world that what I shall all “engaged” philosophy -

political and social theory, aesthetics, the philosophy of history,

existentialism, cultural studies, communications theory, and postmodernism -

should not be the central concern of philosophical speculation (or in many

cases of any concern at all). This is a grand historical mistake, for in all cases

these fields of study migrated from a hostile philosophical environment to more

friendly environments in Political Science, Sociology, English, Communications,

and other departments. The migration has served only to impoverish philosophy.

A

number of interesting historical facts come to mind here. Social theory is full

of thinkers who were either literally philosophers or who had strong

philosophical backgrounds. All of the Enlightenment and its offspring fits in here - Adam Smith, Adam Ferguson, the Marquis de

Condorcet and Auguste Comte. Marx was a philosopher,

amongst other things. George Herbert Mead, one of the most famous early twentieth-century

American social theorists, was a philosopher by education. The school he helped to found, the

This

is especially surprising in the cases of cultural studies and communications

theory, which until recently had no home turf in academe (though communications

programs are proliferating as we speak). The influence of technology and media

on our values, our perceptions and our lives is a fundamentally philosophical

question, as theorists like Marshall McLuhan made all too clear. These are

basic moral and epistemological issues, not just matters for empirical social

research.

5.

Some Statistics

In

this section I will analyse ten representative Canadian universities to show

how the teaching and research areas of full-time faculty there empirically

prove that a “rump parliament” now dominates academic philosophy departments in

this country. I will distinguish here the “hard rump” - the area of the

philosophical parliament in Diagram 2 extending from metaphysics to logic - from

the larger “soft rump” – which is the hard rump plus ethics.

Methodology: I chose ten representative universities from across the country,

excluding the

In general, I counted the first two specializations

listed for each professor as the dominant ones in the absence of evidence to

the contrary. In some cases two listed specializations are so similar that I

combined them, including whatever else is listed as their “second”

specialization. In cases where the main focus of a given specialization was

unclear, I looked at publication titles, courses taught and the other

specializations listed. In cases where only one specialization is listed, I

simply counted it twice.

I only counted full-time (tenure or tenure-track)

professors, excluding instructors/adjuncts/graduate students, whose long-term

influence and position in the power structure of philosophy departments is

minimal (though they may influence their undergraduate students through their

teaching quite heavily). I also excluded retired professors. The total

specializations in a department (T) = the number of full-time professors with

declared specializations (P) x 2.

The “hard” philosophical rump of specializations

includes logic, epistemology,

philosophy of language, cognitive science/analytic philosophy of

mind, the philosophy of science, and the history of philosophy in cases where

the dominant focus seemed to be logic, epistemology or “hard” metaphysics. The

soft rump includes all of the above plus ethics of all types since in most

cases ethicists take an analytic approach to their work. To balance the few

cases where they don’t, I included a number of vague “history of philosophy”

specializations in a neutral category, including all listings of ancient

philosophy, even though a substantial proportion of these historians of

philosophy do, in fact, take an analytic approach indistinguishable from that

of the “hard” rump. I also considered political and social philosophers as

outside the soft rump despite the fact that many of them take an analytical or

logical approach to their work, and are thus allied to the hard rump parliament

of philosophy.

|

University |

Total of FT

Professors[3] |

Number of

Specializations in Hard Rump |

% of those in

Department |

Number of

Specializations in Soft Rump |

% of those in

Department |

|

UBC |

16 |

25 |

78% |

27 |

84% |

|

|

21 |

22 |

54% |

32 |

76% |

|

|

15 |

15 |

50% |

21 |

70% |

|

|

12 |

12 |

50% |

17 |

71% |

|

Western |

32 |

39 |

61% |

51 |

80% |

|

|

12 |

17 |

71% |

20 |

83% |

|

Queen’s |

19 |

18 |

47% |

28 |

74% |

|

|

22 |

22 |

50% |

27 |

61% |

|

McGill |

22 |

21 |

48% |

27 |

61% |

|

Dalhousie |

13 |

16 |

61% |

25 |

96% |

|

TOTALS |

184 |

207 |

56% |

275 |

75% |

Totals of Declared

Specialisations

The Hard Rump

Parliament of Philosophy

Logic

(includes Critical Thinking, Philosophy of Mathematics, Decision Theory)=36

Epistemology/Philosophy

of Language=34

Cognitive

Science/Philosophy of Mind/Analytic Metaphysics=41

Philosophy

of Science (all types)=67

“Hard”

History of Philosophy (focus on logical, epistemology, analytics)=26

The Soft Rump

Parliament

Ethics

(all types)=43

Applied

Ethics (includes Bioethics, Environmental Ethics, Business Ethics)=26

Largely Neutral

Specializations

“Neutral”

History of Philosophy (e.g. ancient)=20

“Soft”

History of Philosophy (i.e. non-analytic)=6

“Soft”

Metaphysics (including Philosophy of Religion, Idealism)=4

Engaged Philosophy

Social

and Political Philosophy (includes Philosophy of Law)=38

Existentialism

& Phenomenology (19th and 20th century continental

thought)=12

Postmodernism

& Post-structuralism=3

Aesthetics/Philosophy

of Art=5

Philosophy

of History=1

Social

Theory=1

Communications

or Cultural Theory=0

A

Summary of the Canadian Parliament of Philosophy (totals for all ten

schools)

Hard

Rump Parliament (logic, epistemology, mind, science): 207 (56%)

Soft

Rump Parliament (add ethics and applied ethics to hard rump): 275 (75%)

Specializations

Outside the Rump (neutral and “engaged” philosophy): 93

(25%)

Analysis:

We

can categorize these ten universities into three groups. First comes the three

“hardcore” analytic schools: UBC,

Next comes four “softcore”

universities where about half the specializations are in the hard rump, with

the soft rump comprising 70-76% in each case: the Universities of Alberta,

There are two partial anomalies to the general rule

that the rump parliament dominates philosophy in

Finally, a few words about how specific

specializations are distributed. The philosophy of science dominates the ten Canadian

departments studied, with 67 specializations. Although ethics comes second with

43 specializations, the next three subfields are all from the hard rump:

analytic metaphysics (41), logic (36) and epistemology (34). Honderich’s idealized “solar system” as a political model

for hiring and promotion in philosophy departments seems to be confirmed by

these statistics. Further, there are only fifteen specializations total for

continental thought of all brands, with four schools not listing a single

full-time professor with a continental philosophy primary specialization.

Statistically, this equates to 0.75 continentalists

per department. This is very strange, given the tremendous influence thinkers

such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Sartre, Camus, Heidegger, Habermas,

Baudrillard, Derrida and Foucault have had on modern

thought and culture. Lastly, there is only one social theorist and one

philosopher of history, and no philosophers of culture or communication, in

these ten departments.

6.

The Anatomy of Philosophical Revolutions

6.

The Anatomy of Philosophical Revolutions

Why did this revolution happen? I suggest a number of causal explanations:

(1) The dominance of modern science in modern bureaucracies and the culture at large, bringing with it an emphasis on empirical experimentation as the ground of all valid knowledge, hence positivism. This lead to a long-term legitimation crisis for academic philosophy: how could the discipline of Plato, Descartes, Hume and Nietzsche win the favour of natural scientists?

(2) This is paralleled

by the bureaucratization of philosophy in large academic institutions that are

either privately funded, as in the

(3) A third likely

cause is an over-emphasis within philosophy of the power of logical and

linguistic analysis to solve important philosophical problems, which was tied

to a sense of national or institutional pride associated in

The final result of

these paradigmatic revolutions is the political hegemony of the analytic rump

parliament in Canadian (and no doubt American and British) philosophy

departments.

7. The Grand Historical Mistake of Modern Philosophy

The grand historical mistake made by modern academic

philosophy is the abandonment of engaged philosophy (broadly conceived) to

other academic disciplines: of parts of political theory to political science,

of social theory to sociology, the philosophy of history to history, of

cultural studies and communications theory to communications, English, and

other programs, and the marginalization of existentialism and modern

Continental philosophy in limited course and research ghettos, if not its total

exclusion (with literature and media studies programs taking up some of the

slack). Added to this is the placement in the intellectual attic of once

moderately important fields of study such as aesthetics, which hasn’t really

been adopted by another academic discipline (though fine arts may occasionally

offer a course in the field). None of this was inevitable - it was the result

of a series of paradigm-defining political decisions by analytic philosophers

who came to define the content of academic philosophy in the twentieth century.

Ironically,

by the 1970s and 1980s, this resulted in criticism in some quarters that

academic philosophy had lost its social relevance. Normally, this wouldn’t

matter to logicians and epistemologists lost in their abstruse speculations.

Yet when student populations and sources of funds started to drop off in the

1980s and 1990s (after all, it’s a notorious fact that administrations always

cut arts programs first when trimming university budgets under pressure from

government cuts), academic philosophers saw their empires crumbling. So they

took what was at hand - logic and largely rationalist ethics - and tried to

“apply” them to social issues. Hence was born critical thinking, business ethics,

ethics for accountants, bio-ethics, and other

“service” courses that in some cases dominate a Philosophy department’s

relation to the student population around it, at least in terms of sheer

numbers. The question whether these courses are successful in

accomplishing their goals - naturally, I am sceptical about this - I leave to

another day. Yet it seems clear that the circumstances of their birth

had a lot to do with putting some bums in the empty seats vacated by students

who no longer saw philosophy as relevant.

Is

it too late to reclaim engaged philosophy for the discipline? I’m not sure,

though bureaucratic institutions, as any student of Max Weber knows, tend to

fight for their territories tooth and nail, rarely agreeing to give up an

administrative province to a rival without some sort of concrete political and

economic pressure. Added to this is the fact that most current academic

philosophers who run Philosophy departments don’t want these lost provinces

back anyway, being proud of their splendid isolation from engaged philosophy.

Yet there are no inevitabilities in the history of ideas. Surprising things

sometimes do happen - to return to my political metaphor, ancien

regimes collapse, Cold Wars end, kings are

guillotined. If they do, then it will be not the worst of times, but the best

of times, a spring of hope after a winter of despair (with a tip of the hat to

Mr. Dickens).

Bibliography

Honderich, Ted ed. The

Hume,

David. A Treatise of

Human Nature. Ed. L. A.

Selby-Bigge.

Russell,

Betrand. The Problems of Philsophy.

University websites for UBC,