Morpheus: The Matrix is everywhere, it is all around us, even now in this very room. You can see it when you look out your window, or you turn on your television. You can feel it when you go to work, when you go to church, when you pay your taxes. It is the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth.

Neo: What truth?

Morpheus: That you are a slave, Neo. Like everyone else, you were born into bondage... born into a prison that you cannot smell or taste or touch. A prison for your mind.

The Matrix

![]()

Introduction

The question "what is the Matrix?" is the mantra repeated both within and without the film, in its text, sub-text, and super-text (i.e. the ads that promote it). There are least three answers to this question that dialectically interface with each other and which live and breathe in a network of simulated theoretical consciousness that thinks intensely about the modern metaphysics of culture. This movie explores the relationship between reality and simulacra, the images that dominate and permeate every aspect of our being. It is also a deeply philosophical and spiritual film that addresses what it means to be real, to have free will, to be a messiah, and to perform miracles. In this paper we shall consider the answers to the mantra and interpret the film's postmodern critique of culture by examining three philosophical and spiritual themes explored within it, in an ascending order of the extent to which each cuts closest to the hermeneutical core of the film.(1)

Answer 1: The Matrix is a twisted version of the story of a savior come to redeem lost souls from the programmed semi-reality

of the modern military-industrial -entertainment complex, but which calls into question the value of redemption and

deconstructs the categories of salvation and terrorism. In this section we argue that the question we should be asking ourselves

is not so much "What is the Matrix?," but "What is the cipher?" that acts as the key to the Matrix.

Answer 2: The Matrix is a re-telling of Descartes' dream of the evil demon come to trick him into believing that everything he senses and thinks is false.

Answer 3: The Matrix is a story about simulacra, simulations of the real, which Jean Baudrillard describes as "that which never hides the truth, but hides the fact that there is none" (1994a, 1).(2)

Part I. Redemption or Terrorism? Two Descriptions of the Hyperreal

Now it is high time to awake out of sleep: for now is our salvation nearer than when we believed (Romans 13:11).

The most obvious reading of this film is to chalk it up as being yet another Christian redemption story. Read Mercer Schuchardt writes:It is not without coincidence that The Matrix was released on the last Easter weekend of the dying 20th Century. It is a parable of the original Judeo-Christian world-view of entrapment in a world gone wrong, with no hope of survival or salvation short of something miraculous. The Matrix is a new testament for a new millennium, a religious parable of mankind's messiah in an age that needs salvation as desperately as any ever has. ("Parable, Experience, Question, Answer")

There is much evidence in the film to support such a reading. But one can advance a radically different interpretation, that The Matrix actively deconstructs the categories of redemption and terrorism, indicating that the simulated reality of the Matrix is just or even more authentic than the post-eco-holocaust "desert of the real" to which Morpheus and his followers would subject the inhabitants of the Matrix in their redemptive crusade. This film is multifaceted and cannot be reduced to a simple dramatization of the struggle between good and evil; rather, it blurs this distinction, calling into question the foundations of our Western binary moral codes.

We do not learn until well into the film that the Matrix is simply digital data that creates a dreamworld for its prisoners. Nothing in the world of the film is "real" - everything is simulation, created by artificial intelligence machines (AIs). Morpheus (played by Laurence Fishburne) explains this to Neo (Keanu Reeves) after he is reborn into "reality." Significantly, "Morpheus" was the god of dreams in Greek mythology. His name connotes the ability to change, which is fitting, because our Morpheus has considerable control over the dreamworld of the Matrix, being able to break many of its supposed physical laws. He explains to Neo that sometime in the late twentieth-first century there was a conflict between human beings and the artificial intelligence machines they had engineered. The humans thought they could destroy the AIs by cutting off their energy source, sunlight. A war ensued, the sun was blackened, and the earth became a wasteland. The computers survived the catastrophe by enslaving humans and using them as living batteries. In the age of the Matrix, human beings are not born; they are grown and tended by machines in huge fields of biopods. Babies are plugged into the Matrix, where they live out their lives in a simulated reality of late twentieth-century earth, the so-called "height of human civilization." Humans are a renewable resource for the AIs: even when they die, they are fed intravenously into the living. The Matrix is a simulation, but the minds that inhabit it are "real."

The Matrix is policed by "agents," AIs living a simulated reality as FBI-type lawmen. They have superhuman strength and speed, and are able to bend and break some of the rules of the Matrix's code. Although most human beings really "live" in the fields (and mentally in the Matrix), there is a colony of humans in Zion, the last human city, near the earth's core, where it is still warm. The name Zion is, of course, saturated with biblical significance; it is the ancient name of Jerusalem and the heavenly city where the righteous will be saved after the destruction of the world. The children of Zion represent a threat to the AIs and the Matrix. The agents' goal is therefore to attain the codes that allow entry into Zion's mainframe computer to destroy it. Morpheus tells Neo that early in the history of AI domination, there was a man who could change the Matrix, liberating many people from it. It has been foretold by the Oracle that another such ONE will come again to save the world (note that Neo's name is an anagram of the word "one"). Morpheus, the leader of a group resisting the Matrix's VR world, believes that Neo is this one, although we learn that he has been wrong before.

The agents have identified Neo, AKA Thomas Anderson, as "his next target." They speak of Morpheus as a terrorist, who periodically "targets" inhabitants of the Matrix to join their resistance movement. When Agent Smith (played with admirable sang froid by Hugo Weaving) interrogates Neo after he has been apprehended, he says:

Agent Smith: We know that you have been contacted by a certain individual, a man who calls himself Morpheus. Now whatever you think you know about this man is irrelevant. He is considered by many authorities to be the most dangerous man alive. My colleagues believe that I am wasting my time with you, but I believe that you wish to do the right thing. We're willing to wipe the slate clean, to give you a fresh start, and all we're asking in return is your cooperation in bringing a known terrorist to justice. (From the film)

Morpheus' role is both redemptive and terroristic since his project is to end life as billions now know it, to "save" them from

their delusions and redeem them into the desert of the real, a wasteland worthy of Old Testament prophets' wanderings.

Terrorism is the only effective way to resist the hegemony of a technologically created hyperreality. The only way to break the

spell is to kill the witch, but those under her spell will suffer greatly after it is broken. Like all terrorist groups, Morpheus and

his cohorts are religious fanatics, quite ready to die in suicide missions. Morpheus functions as both God and the father to the

group, which anyone familiar with Freud's psychology of religion will not find too surprising. They are guided by an Oracle,

and they have faith that "the One" will come again to redeem humanity from the illusory world created by the Matrix so that

all will see the Way, the Truth, and the Light.

Morpheus' role is both redemptive and terroristic since his project is to end life as billions now know it, to "save" them from

their delusions and redeem them into the desert of the real, a wasteland worthy of Old Testament prophets' wanderings.

Terrorism is the only effective way to resist the hegemony of a technologically created hyperreality. The only way to break the

spell is to kill the witch, but those under her spell will suffer greatly after it is broken. Like all terrorist groups, Morpheus and

his cohorts are religious fanatics, quite ready to die in suicide missions. Morpheus functions as both God and the father to the

group, which anyone familiar with Freud's psychology of religion will not find too surprising. They are guided by an Oracle,

and they have faith that "the One" will come again to redeem humanity from the illusory world created by the Matrix so that

all will see the Way, the Truth, and the Light.

Neo is clearly a messianic figure. When his friend comes to his door early in the film to buy some illegal clips, he says: "You're my savior, man!" thus foreshadowing Neo's role in this film. Like "Morpheus," the name Neo is significant. It means "young," "new" or "recent," but can also signify "new world." As already noted, it is an anagram for the word "one." Neo is the hope of the Nebuchadnezzar's motley crew for the new world, free of artificial intelligence. He is a high-tech redeemer and the new Christ.

The agents have identified Neo as a trouble-maker and a potential "target" of Morpheus. Moreover, like Morpheus, he is a terrorist (at least in the virtual sense), a hacker who is guilty of every computer crime in the book. Thus they "bug" him, presumably to monitor his contact with Morpheus. In horror film fashion reminiscent of the parasites in Cronenberg's Shivers (1975), a hybrid electronic-organic "bug" is released onto his belly and burrows its way into his body through his navel. In the next scene, Neo starts up from his bed, remembering the harrowing experience as "just a dream."

Yet he later gets a phone call from Morpheus asking to meet him. Neo is picked up by Trinity (Carrie-Ann Moss), Apoc and Switch, and is horrified to discover that the bug he thought he only dreamed of was "real" when Trinity sucks it out of his stomach with a bizarre mechanical pump. Neo had already met Trinity a few scenes earlier when he got a message over his computer to "follow the white rabbit" (one of the several Lewis Carroll references in the film). Seeing a tatoo of a white rabbit on Choi's girlfriend Dujour's arm when they visit Neo's apartment, he accompanies them to a dance club, where he meets Trinity for the first time. The significance of Trinity's name is so obvious that it hardly merits comment. She is part of a holy trinity composed of Morpheus the father, Neo the son, and Trinity the holy spirit. We discover later that the essential characteristics of Trinity, the holy spirit, are faith and love.

Trinity brings Neo to see Morpheus in a dank and depressing Escher-style building. He offers Neo two pills, a red pill which would allow him to see the world as it "really is," and a blue pill that would let him wake up in his bed and remember everything as a dream. Neo chooses the red pill, which turns out to be a tracer so that he can reconnect with his "real" body in the growing fields and rejoin Morpheus, Trinity and the others on their ship, the Nebuchadnezzar, a sort of submarine/hovercraft pirate ship that sails beneath the surface of the devastated real world, hacking periodically into the virtual reality of the Matrix. Significantly, Nebuchadnezzar was a biblical Babylonian king who searched for meaning in his dreams. Morpheus and his crew are searching for meaning in the dreamworld of the Matrix, in the hope of destroying it and awakening its captives. Awakening the dreamers to witness the reality of Jehovah is a quintessentially Christian project: Awake thou that sleepest, and arise from the dead, and Christ shall give thee light (Ephesians 5:14).

Once Neo is reconnected to his body, he is literally reborn, emerging from his biopod covered in blood and goo. This rebirth is clearly symbolic of a baptism. Since Morpheus provides the opportunity for Neo to be "born again," he may also be seen as a John the Baptist, he who recognizes the ONE, and baptizes Him. Once aboard the Nebuchadnezzar, Neo's body must be hooked up to electrodes and pierced with acupuncture needles because his real muscles have never been used and are thus severely atrophied. He asks Morpheus "why do my eyes hurt?" Morpheus replies: "You have never used them before." This sentence is obviously metaphoric for the Christian message: Verily verily I say unto thee, except a man be born again he cannot see the kingdom of God (John 3:3).

For the first time in his life, Neo's body is connected physically to his mind. He awakens from his dream and sees the world as it really is. Unfortunately, the kingdom of God is not a particularly pleasant place. It is a world in which the sun is blackened, the earth's surface ravaged, where people can only live near the earth's core. Life in the real world is bleak. At this point, his training begins. Neo is hooked up to a mini-Matrix operated from the ship's bridge: Tank loads combat programs onto the ship's computer, which Neo absorbs through his mind. His body is never involved in the training. He becomes proficient in Kung Fu and other martial arts. Finally he "fights" Morpheus in a simulated Zen-like gymnasium where they are both "plugged into" a computer simulation program. Neo is so impressed by the simulacrum, he cannot believe it is not real. Morpheus asks: "How would you know the difference between the dream world and the real world?" This question is crux of the entire film, hinting at Descartes' meditations, as we shall soon see.

Hyperreality, like reality, is based on rules. The purpose of Neo's training in the martial arts is to learn how to bend and break these rules in order to manipulate the Matrix and defeat the agents. Essentially he is learning to "walk on water" - i.e. to perform miracles. As with any terrorist group, soldiers must be trained to defeat the enemy, which is always "the system," taken in some sense of this word. Needless to say, miracles are pretty effective terrorist tactics not only to physically overpower the enemy, but also to win converts to the cause. Our heroes must hope that the drowning Egyptians don't learn how to walk on water too before the waves consume them.

Sometime later, Neo and Cypher (Joe Pantaliano) look at the code that flashes across the screen. Neo is incredulous that Cypher can de-cipher it. The latter explains that he can't even see the code anymore: he reads it as a blond, a brunette, or a red-head, i.e. the simulacra that the code represents. Like all other monikers in the film, "Cypher" is a meaningful name. The word "cipher" can mean "the number zero" or "a person who has little or no value." More importantly, it can mean "a system of secret writing based on a set of symbols" or "a message in such a system." Not surprisingly, Cypher's job on the ship is to read the computer code or the "secret writing." Later, we see that he is the messenger of an important truth: That the war between humans and AIs is over and that the AIs have won. This in fact can be viewed as the "cipher" of the entire film, the Wachowskis' hidden prophecy that we are inescapably committed to living out our lives in a hyperreal culture.

Cypher also plays the Judas figure in this film, betraying Morpheus (the only person with access to the codes for Zion's computer mainframe) to the agents over a meal of succulent steak (the film's equivalent of Judas' pieces of silver). He says to Agent Smith "I know this steak doesn't exist," yet revels in its taste all the same. He concludes, "Ignorance is bliss." Read Mercer Schuchardt makes some interesting observations regarding the steak scene in his web essay on The Matrix:

It is immensely significant that Cypher's deal-making meal with the agents centers around steak. First, meat is a metaphor that cyberspace inhabitants use to describe the real world: meat space is the term they use to describe the non-virtual world, a metaphor that clearly shows their preference for the virtual realm. Cypher says that even though he knows the steak isn't real, it sure seems like it. The stupidity and superficiality of choosing blissful ignorance is revealed when Cypher says that when he is reinserted into the Matrix, he wants to be rich and "somebody important, like an actor." It's a line you could almost pass over if it wasn't so clearly earmarked as the speech of a fool, justifying his foolishness. But meat is also the metaphor that media theorist Marshall McLuhan uses to describe the tricky distinction between a medium's content and form. As he puts it, "The content of a medium is like a juicy piece of meat that the burglar throws to distract the watchdog of the mind." ...The Matrix itself is designed, like Huxley's brave new world, to oppress you not through totalitarian force, but through totalitarian pleasure. ("Parable, Experience, Question, Answer")

While we certainly agree with Schuchart's allusion to McLuhan, Cypher is no simple fool, no mere pawn in the AIs' game. His betrayal is particularly interesting because his motives are so rational. He is clearly extremely angry with and oppressed by Morpheus, who he portrays as a kind of slave-driver. When Cypher and Neo share a drink together he says: "I know what you're thinking, because right now I'm thinking the same thing... Why, oh why didn't I take the blue pill?" Reality is extremely bleak and uncomfortable on the Nebuchadnezzar. Moreover, Cypher is no more free on the ship than he was in the Matrix. In both situations he is working to benefit others; the difference is that in the Matrix he at least has the illusion of being free and the experience of a pleasant life, while on the ship he feels oppressed. From Cypher's standpoint, there can be no point to "saving" people from the Matrix, because the Matrix is, by any measure, a much more pleasant place to live than "reality." To him Morpheus's entire project of redemption is deluded and misguided.

Moreover, the vast majority of the people in the Matrix (both in the film and, one would imagine, in the film's audience) have

no desire to be "redeemed." Cypher forces the audience to ask a serious question: "If Neo is the ONE, from what is he

redeeming the world? Where is the evil in the Matrix? How is it fundamentally different from the world in which we live

today?" The answer to the last question is that there is no difference. We are living in a world saturated by simulacra

controlled by mega-powers beyond our ken. We think we have choices, but we don't. We think we are free, but we aren't.

Our bodies are batteries that provide the energy for the work of nameless, faceless corporations. Most of us in the Western

world are corporate slaves. Even if we are not entirely happy, we are for the most part unwilling to make meaningful changes

in our lives. Most of us would never forsake our hyperreal world for the desert of the real. If someone like Morpheus were to

come along to "liberate" us, we would see him as an arrogant, self-righteous and fanatical terrorist, come to replace our

comforts and conveniences with his unattractive version of reality, complete with a new set of dictates on how we must now

live our lives (media castigate Ted Kaczynski, AKA the Unabomber, had the same sort of project in mind, which he hoped to

accomplish by postal terrorism). Most of us would prefer to stay asleep and blind, to not be "born again." If Morpheus's desert

of the real is the kingdom of god, he can keep it. This position is not superficial, foolish, or ignorant: it is pragmatic. Any

freedom that might be experienced on the Nebuchadnezzar is as illusory as the freedom one feels in the Matrix. Human beings

are never free. The film makes this point perfectly clear, and as such effectively deconstructs the categories of salvation and

terrorism. From Cypher's perspective, Morpheus and his crew are a group of terrorists, and he is leaving them to rejoin

legitimate society.

Moreover, the vast majority of the people in the Matrix (both in the film and, one would imagine, in the film's audience) have

no desire to be "redeemed." Cypher forces the audience to ask a serious question: "If Neo is the ONE, from what is he

redeeming the world? Where is the evil in the Matrix? How is it fundamentally different from the world in which we live

today?" The answer to the last question is that there is no difference. We are living in a world saturated by simulacra

controlled by mega-powers beyond our ken. We think we have choices, but we don't. We think we are free, but we aren't.

Our bodies are batteries that provide the energy for the work of nameless, faceless corporations. Most of us in the Western

world are corporate slaves. Even if we are not entirely happy, we are for the most part unwilling to make meaningful changes

in our lives. Most of us would never forsake our hyperreal world for the desert of the real. If someone like Morpheus were to

come along to "liberate" us, we would see him as an arrogant, self-righteous and fanatical terrorist, come to replace our

comforts and conveniences with his unattractive version of reality, complete with a new set of dictates on how we must now

live our lives (media castigate Ted Kaczynski, AKA the Unabomber, had the same sort of project in mind, which he hoped to

accomplish by postal terrorism). Most of us would prefer to stay asleep and blind, to not be "born again." If Morpheus's desert

of the real is the kingdom of god, he can keep it. This position is not superficial, foolish, or ignorant: it is pragmatic. Any

freedom that might be experienced on the Nebuchadnezzar is as illusory as the freedom one feels in the Matrix. Human beings

are never free. The film makes this point perfectly clear, and as such effectively deconstructs the categories of salvation and

terrorism. From Cypher's perspective, Morpheus and his crew are a group of terrorists, and he is leaving them to rejoin

legitimate society.

After Neo's training, Morpheus decides that the time is right to take him to see the Oracle, an old woman who has functioned as a prophetess since the beginning of the resistance. Everyone on the ship except Tank enters the Matrix. When Neo finally meets this middle-aged, charming black woman, she tells him not to mind the vase, at which point Neo trips and knocks it over. In this scene, the Oracle plays with the concepts of free will and fate. The act of prediction influences the course of events, just as the behavior of electrons changes when they are observed using light photons. The Oracle asks Neo: "So, what do you think? You think you're the One?" Neo answers "I don't know." To this the Oracle replies "Know thyself," the inscription over the ancient Temple of Delphi wherein a more venerable oracle gave her prophecies to all and sundry (the Latin version adorns a wooden plaque hanging above her kitchen door). She goes on to say that being the ONE is like being in love. There's no question about it, one just knows. Since Neo does not know it (yet), he is not the One, at least according to her. "I'm not the One?" Neo asks, to which the Oracle responds, "Sorry, kid. You got the gift, but it looks like you're waiting for something." Later that day, Neo dies and is resurrected by the faith and love of the holy spirit (Trinity) and becomes the ONE, the miracle worker who can stop bullets, having become fully aware that the Matrix is not really "there." Ultimately the Oracle does foretell the future. He becomes the one, but in another life. As such, Neo is at once fated and free, both the One and not the One.

At this point, Cypher has betrayed the group to the agents, who are now hot on their trail. They are specifically interested in Morpheus because he has the codes to Zion's mainframe computer. Cypher asks for an exit and rejoins his body on the ship, where he subsequently shoots Tank and begins the process of unplugging the others' bodies on the ship (thus murdering them). During this process he calls Trinity, with whom he has been in love for many years, to explain his motives:(3)

Cypher: You see the truth, the real truth is that the war is over. It's been over for a long time. And guess what? We lost! Did you hear that? We lost the war!

Trinity: What about Zion?

Cypher: Zion? Zion is a part of this delusion. More of this madness. That's why this has to be done. It has to end, now and forever. (She suddenly sees the entire dark plan.)

Trinity: Oh my God, this is about Zion. You gave them Morpheus for the access codes to Zion.

Cypher: You see Trinity, we humans here have a place in the future. But it's not here, it's in the Matrix.

Trinity: The Matrix isn't real.

Cypher: Oh, I disagree Trinity. I think the Matrix is more real than this world. I mean, all I do is pull a plug here. But there you watch a man die. (He grabs hold of the cable in Apoc's neck, twists it and yanks it out.) You tell me which is more real. (Apoc seems to go blind for an instant, a scream caught in his throat, his hands reaching for nothing, and then falls dead. Switch screams.) Welcome to the real world, right?

Trinity: Somehow, some way, you're going to pay for this.

Cypher: Pay for it? I'm not even going to remember it. It'll be like it never happened. The tree falling in the forest. It doesn't make a sound.

Trinity: Goddamn you Cypher!

Cypher: Don't hate me Trinity, I'm just the messenger. And right now I'm going to prove that the message is true. (Screenplay 1996)

A cipher is a "secret message," and in this passage Cypher represents himself as a messenger. We shall see in the third part of this paper that Cypher's perspective on hyperreality is quite Baudrillardesque, and is probably the final position held by Larry and Andy Wachowski. The film then is not (just) a story about good defeating evil, as Schuchardt argues; instead, it is a multi-faceted description of our own hyppereal culture; an assessment that the war has already been won by the controllers of technology; and that our concept of the real is a utopia that no longer exists.

Cypher then asks Trinity if she believes that Neo is the ONE. Trinity says that she does. Cypher laughs at this, bragging that "I mean if Neo's the one, then there'd have to be some kind of a miracle to stop me." As it turns out, a miracle does occur, and a "resurrected" Tank kills Cypher before he is able to unplug Trinity and Neo.

When the agents finally have Morpheus in their grasp, they begin the process of "hacking into his mind" to obtain the codes. Morpheus proves surprisingly resistant to their efforts, so the agents begin playing mind games to wear him down. During an important exchange, Agent Smith explains that this Matrix is not the original one. The first Matrix attempted to simulate a garden of Eden, a perfect world, free of pain and suffering. The human minds could not accept such a world because they define their existence by suffering. As a result, a second Matrix had to be constructed. This story echos the Genesis story of original sin and the fall from grace. In this case, however, the AIs are God.

Back on the ship, Trinity and Neo realize that Morpheus is vulnerable to the agents' interrogation, and, as a result, that Zion is in danger. Tank and Trinity decide that the only thing to do is pull the plug on Morpheus to save Zion. Neo stops them, having resolved to dive back into the data pool of the Matrix to rescue Morpheus. If he is truly the One, he will be able to defeat the agents, even though all the previous prophets have failed (and thus proven themselves false). Trinity, as Neo's commanding officer, insists on coming along. They enter the Matrix and liberate Morpheus (after blasting their way through walls of security guards and swat teams). Morpheus and Trinity exit successfully in a subway phone booth, leaving Neo behind. Just as he is about to exit, he is confronted by Agent Smith, his old nemesis. Several minutes of acrobatic hand to hand combat ensue; Neo temporarily gets the upper hand, but is eventually killed. Thus Neo dies to redeem Morpheus as well as the children of Zion.

Back on the ship, Trinity has become very faithful. She now realizes that Neo is the One, because she has fallen head over heals in love with him, as the Oracle foretold. Although she knows that Neo is dead, her faith in him and her love, incarnated with a princess charming kiss on his real lips, are just what the doctor ordered to resurrect our hero. Once resurrected, he is invincible and able to really "see" the Matrix for what it is - streams of code. Now he can stop bullets and perform other sundry miracles. He has become a divine being, a Herculean demi-god. The obvious spiritual message is that faith is love and that love is stronger than death. Faith and Love are the ultimate strength, more powerful even than Neo's new abilities to halt bullets in mid-flight.

At the end of the movie Neo makes a phone call to the audience. He says:

Neo: You're afraid of change. I don't know the future. I didn't come here to tell you how this is going to end. I came here to tell you how it's going to begin . . I'm going to show them a world without you [the AIs, presumably], a world without rules and controls, without borders or boundaries, a world where anything is possible. Where we go from there is a choice I leave to you.

Ironically, as we shall see in the third part of this essay, the message of the film can be understood to say just the opposite of Neo's closing words. The cipher is the message spoken by Cypher. "You see, the truth, the real truth is that the war is over. It's been over for a long time. And guess what? We lost! Did you hear that - we lost the war."

Part II. Ghosts in the Machine: The Matrix as the Cartesian Evil Demon

Part II. Ghosts in the Machine: The Matrix as the Cartesian Evil Demon

Another way to interpret the world of The Matrix is to see it as a high-tech simulation of René Descartes' experiment with extreme doubt in his Meditations. For the philosophically uninitiated, at the start of this groundbreaking short work, Descartes proposes to doubt all of his previous opinions in order to get at a body of knowledge he knows to be absolutely true. Part of the reason for this campaign of doubt is the fact that his senses have in the past so often played him false:

Everything I have accepted up to now as being absolutely true and assured, I have learned from or through the senses. But I have sometimes found that these senses played me false, and it is prudent never to trust entirely those who have once deceived us. (Descartes 1968, 96)

Indeed, he asks whether his entire life is no more than a dream, wondering whether, in fact, he is dreaming as he writes his first Meditation. But reality intrudes: even the sirens and satyrs of his dreamworld must be constructed from elements of real things. Also, the truths of arithmetic and geometry are true in all possible worlds. In The Matrix we see a parallel process unfolding. When Morpheus is preparing Neo for his first exit from the Matrix, he asks him:

Morpheus: Have you ever had a dream, Neo, that you were so sure was real? What if you were unable to wake from that dream? How would you know the difference between the dream world and the real world? (From the film)

Of course, as Descartes observed, you cannot tell the difference (assuming there is nothing with which to compare the

dreamworld in terms of internal coherence, clarity, brilliance, consistency, etc., as is the case for the dreamers in the Matrix).

Like Descartes, Neo doubts the reliability of his senses, a doubt reinforced by Morpheus's cryptic questions. In the same

exchange, Morpheus compares Neo's waking dream to the adventures of Lewis Carroll's light-hearted heroine, Alice.

...which he soon does, by taking the red pill. But Neo discovers that truth is stranger than fiction as he tumbles down the rabbit hole, finding that it extends much deeper than he ever could have imagined.Morpheus: I imagine that right now you're feeling a bit like Alice, tumbling down the rabbit hole? Hmm?

Neo: You could say that.Morpheus: I can see it in your eyes. You have the look of a man who accepts what he sees because he is expecting to wake up. (From the film)

The Matrix is made up of a series of code to which some fairly rigid rules apply. Its inhabitants are, for the most part, required to follow the basic laws of physics. The point of Neo's simulated training is to learn to bend and break these laws while in it, to defeat the AIs and ultimately to liberate the captive dreamers. Indeed, the illusion of the Matrix would be broken if the AI machines were able to change it whenever they fancied. Even when small changes are made (in one case, to surround a virtual building where our heroes are hiding out with brick walls), we see the intervention heralded by a "glitch" in the VR program, like the skipping of a record needle: Neo witnesses two identical black cats walk by a doorway. Needless to say, the cats announce upcoming bad luck for our protagonists and show us the "black magic" of the AIs, who can change the structure of the Matrix at will. The agents in the Matrix, however, usually follow the rough and ready rules of physics: Trinity is able to shoot one point-blank in the head and at least temporarily dispose of him. Of course, since they are pure computer code, they have the power to re-simulate themselves in other virtual bodies. They are effectively immortal until Neo gains the ability to decode and reshape the Matrix to conform to his own will. In short, even the agents cannot (usually) defy the rules of their own code, although they can always rewrite a virtual report of the results of any battle by infesting the consciousness of yet another hapless denizen of the Matrix.

Descartes, like the crew on the Nebuchadnezzar, has faith that a divine being is the author of the universe. But he asks:

To guide (or misguide) him on his way to certain knowledge, Descartes invents an evil demon, a sort of anti-God, whose diabolical goal is to deceive him about everything he has ever believed:...who can give me the assurance that this God has not arranged that there should be no earth, no heaven, no extended body, no figure, no magnitude, or place, and that nevertheless I should have the perception of all these things, and the persuasion that they do exist other than as I see them? (98)

I shall suppose, therefore, that there is, not a true God, who is the sovereign source of truth, but some evil demon, no less cunning and deceiving than powerful, who has used all his artifice to deceive me. I will suppose that the heavens, the air, the earth, colors, shapes, sounds and all external things that we see, are only illusions and deceptions which he uses to take me in. (100)

We find out that this demon plagues him with doubt not only about the reports of the senses, but about the established conclusions of philosophy, mathematics, and even common sense. Descartes has voluntarily put himself, via a thought experiment, into a 17th century version of virtual reality, where nothing his senses tell him is true. Mind you, he, like the crew of the Nebuchadnezzar, never questions whether or not reality has an essence to which his descriptions can correspond; he takes this on absolute faith. He only worries that his descriptions do not correspond to the essence of reality. He has, in short, inserted himself into a Matrix of illusion. Descartes' fantasy, like the Matrix, supposes that reality has an essence and that his descriptions of it are completely wrong because of the deception of an evil demon. If the film shows us the Cartesian dreamworld of hyperbolic doubt, then the puppet-masters who created this world, the AI machines that constructed the Matrix to make its dwellers happy with their role as human batteries, are the evil demons who haunt Descartes' imagination.

But there is one thing of which Descartes feels he can be sure: there is something or someone being deceived. The evil demon has a plaything, although it's not immediately clear what that plaything is. After stripping away the reality of his body, external bodies, and even of certain elements of the thinking process itself, he goes on in his second Meditation to conclude that there can be no doubt that he is thinking, whether or not his thoughts accurately reflect the nature of external reality. The proposition that "I exist as a thinking thing" must be true even if the objects of my thought are fundamental misrepresentations of the way things really are. He thus provides pop philosophy one of its most popular clichés, "I think, therefore I am."

The same can be said of Neo: he obviously thinks, and therefore is. But it's not entirely clear just what "he" is, or whether the world around him is really there (however clearly and distinctly he seems to sense it). Like Descartes' oar in the water, which appears crooked although he reasons that it must be straight, Neo's world streams into his consciousness full of splinters and unauthentic fragments of data that stick in his craw. And as in Descartes' doubt experiment, there is an evil demon in Neo's world, the AI machines that established and maintain the Matrix.

When Neo takes the red pill that awakens him from his dreamworld into the less seductive reality of the post-eco-holocaust Earth, we see Descartes' doubt experiment at work writ large. But unlike Descartes, Neo has to return to the dreamworld of the evil demons, first to visit the Oracle, a Delphic-like priestess whose pronouncements are no clearer than the original conundrums of the Pythian Prophetess; later to save his mentor Morpheus, who has been caught by the Matrix's virtual Gestapo; and lastly, after his second rebirth, as a sort of Bodhisattva to the unenlightened.

In another Cartesian metaphor, the inhabitants of the Matrix walk about like the automata Descartes imagines lurking outside his window. They are literally "cloaked" in streams of data and inserted into each others' dreams.(4) We get a startling sense of this when Neo and Morpheus, after Neo's training is apparently complete, enter what appears to be the Matrix itself. Neo's gaze is distracted by the passing of a pretty woman in red (a creation of Mouse, the ship's programmer), and an agent sneaks up behind him and pulls a pistol. Morpheus pauses the program and everyone in the crowded street freezes except the two of them. In this case, other people are indeed automata, very realistic conglomerations of electrical signals sent to Neo's cortex, providing him with the illusion of other living beings.

The quest for perfection represents another Cartesian element in The Matrix. In his third Meditation, Descartes brings to the fore the classic medieval proof of god's existence, the ontological argument. He contends that nothingness cannot be the cause of anything; that the more perfect has greater "reality" than the less perfect, and further, that perfection cannot be the product of imperfection. There must be greater perfection and reality in the cause of the universe than its effects (for example, us). Therefore God exists, in so far as we can imagine perfection, and this perfection cannot be the product of our feeble minds. In The Matrix, we find a reference to the creation of such perfection when Agent Smith interrogates a bound and helpless Morpheus. He tells Morpheus that the initial Matrix created by the AIs gave its human prisoners a perfect life, free of pain and suffering, and how this construct was a disaster, as its prisoners rejected the illusions it created en masse. "No one would accept the program. Entire crops were lost." Smith speculates that there is something about the human mind that cannot live with such perfection. We are imperfect creatures as compared to the AIs, who are, quite literally, godlike. Paradoxically, here we see the ontological argument in reverse: how could imperfect human minds have created such sublime beings? Smith apparently never considers this question, treating evolution as a haphazard process, full of fits and starts, whereby an imperfect species too much in love with corporeal reality (i.e. us) accidentally brings into being its own successors, who become masters of the planet.

In a private soliloquy to Morpheus - Smith takes out his earpiece, which we can take as symbolic of his disconnection from the Borg-like commonality of the world of the AIs - he divulges that he feels himself becoming corrupted by the simulated sensory overload of the Matrix, notably, the stench (he sniffs Morpheus's sweat to make his point):

Agent Smith: I hate this place. This zoo. This prison. This reality, whatever you want to call it. I can't stand it any longer. It's the smell, if there is such a thing. I feel saturated by it. I can taste your stink. And every time I do I feel I have somehow been infected by it. It's repulsive, isn't it? . . . I must get out of here, I must get free. And in this mind is the key, my key. (From the film)

His crystalline consciousness seems to be drawn down into the corporeal realm (despite the fact he has no real body): his perfection is in danger of fragmenting. Yet he explains how the replacement of human dominance on the planet by the rule of the AIs is a necessary evolutionary step, a freeing of mind from the corruptions of the body. In Agent Smith's account of evolution, the thinking things must sever their links with this corporeal realm to move forward toward a purer transcendence.

The classical philosophical problem of freewill and fate as represented in the film also echoes Cartesian themes. When Neo

goes to visit the Oracle, she tells him not to worry about breaking a vase, which Neo proceeds to do when he whirls around in

confusion. Then she puts forward the riddle to Neo: "What's really going to bake your noodle later on is, would you still have

broken it if I hadn't said anything." She also asks him if he believes in fate (as had Morpheus earlier in the film). He says no,

for he doesn't like the idea of not being in control of his life.(5) Descartes, like Neo, also makes the case for freewill, saying that

he is conscious of "possessing a will so ample and extended as not to be enclosed in any limits." He can will anything; but the

limitations of his body and of the external world prevent him from carrying out these projects. Similarly, in the Matrix, the

characters can will anything they like; but they are bound by its rules, just as we are bound by the laws of physics. But, as

Trinity tells Neo while driving to the Oracle: "The Matrix cannot tell you who you are." The Cartesian rational ego may be

totally deluded, but it can still construct itself as a free, unique entity. The liberation that the coming of Neo as "the One"

promises, is based on this premise of metaphysical free will. Neo is at least potentially free to break the chains of the Matrix

that held him prisoner for most of his life.

The classical philosophical problem of freewill and fate as represented in the film also echoes Cartesian themes. When Neo

goes to visit the Oracle, she tells him not to worry about breaking a vase, which Neo proceeds to do when he whirls around in

confusion. Then she puts forward the riddle to Neo: "What's really going to bake your noodle later on is, would you still have

broken it if I hadn't said anything." She also asks him if he believes in fate (as had Morpheus earlier in the film). He says no,

for he doesn't like the idea of not being in control of his life.(5) Descartes, like Neo, also makes the case for freewill, saying that

he is conscious of "possessing a will so ample and extended as not to be enclosed in any limits." He can will anything; but the

limitations of his body and of the external world prevent him from carrying out these projects. Similarly, in the Matrix, the

characters can will anything they like; but they are bound by its rules, just as we are bound by the laws of physics. But, as

Trinity tells Neo while driving to the Oracle: "The Matrix cannot tell you who you are." The Cartesian rational ego may be

totally deluded, but it can still construct itself as a free, unique entity. The liberation that the coming of Neo as "the One"

promises, is based on this premise of metaphysical free will. Neo is at least potentially free to break the chains of the Matrix

that held him prisoner for most of his life.

The last major Cartesian theme in The Matrix is that of mind/body dualism. Descartes took the position that although mind and body are composed of different substances, and that on one level we can see the mind as a sort of pilot in the ship of the body, they are closely related and form a single whole. We can see the intermingling in the mind/body relationship in phenomena like the phantom pain in non-existent legs experienced by amputees. Of course, on one level we can see the theme of mind/body dualism as the meta-theme of The Matrix. The whole concept of virtual reality is premised on Cartesian dualism: the body is shut down, while the mind is plugged into an alternative reality controlled by computer programs. More specifically, there is a sense of mind/body intermingling in a dialogue between Morpheus and Neo just prior to Neo's reinsertion into the Matrix. Neo asks, "If you are killed in the Matrix, do you die here," to which Morpheus replies: "The body cannot live without the mind," thereby reversing Descartes' concerns about the mind being too dependent on the body (with its unreliable sensory reports, physical drives, and troublesome emotions). We see visible evidence of this dependence on the bodies of those plugged into the Matrix when suffering virtual pain or bodily abuse: shaking, bloody noses, sweat, etc. In both the Cartesian and Wachowskian universes, mind and body are separate yet closely related.

Thus The Matrix can be understood in terms of a modern version of the Cartesian dreamworld created by an evil demon, but which, paradoxically, leads to the certain knowledge that: "I think therefore I am." It pushes the mind/body problem to its theoretical limits while exploring free will and determinism in the artificial world created by the Wachowski brothers' thought experiment cum film. By any account, such weighty philosophical matters are more than what most Hollywood films ever hope to address. Nevertheless, the Wachowski brothers did not end their philosophical explorations in the seventeenth century. They plunge headlong into a cutting-edge postmodern critique of culture, consciously exploiting the ideas of cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard to illustrate an important point about the Matrix of our culture in which we find ourselves at present.

Part III. The Matrix as a Simulacrum of the Desert of the Real

Part III. The Matrix as a Simulacrum of the Desert of the Real

For those who still believe in authorial intention, and that interpreting art and literature should involve assessing evidence and forming hypotheses about what the author meant to say, it can hardly be doubted that the theoretical source par excellence for The Matrix is Jean Baudrillard's theory that modern culture is a desert of the real in which hyperreal simulacra saturate and dominate human consciousness. There is much evidence in the film and screenplay to support the priority of such an interpretation. In the Construct, for instance, before Neo begins his training, Morpheus invites him to watch a 60s-era color console TV, suggesting a nostalgia for an earlier era of technology. On it we see representations of street life in our own day; then, a jarring switch to dark and devastated cities, the post-holocaust Earth. Morpheus, with great ceremony, announces this shift to Neo with the following pronouncement:

Welcome to the desert of the real.

The "desert of the real" is a classic Baudrillardesque metaphor. In this film, the Wackowskis argue along with Baudrillard that there is no longer a reality to which we can return because the map of the landscape (the simulacra) has replaced most of the original territory. All that remains of it is a barren and forsaken desert.

Baudrillard uses this metaphor to suggest that what was once the real territory that the map simulated, is now a barren, lifeless desert, unclaimed by the Empire. Its domain is now the simulacra, the map, because reality either no longer exists or has become so dry and apostatized that it is of interest to almost no one. How this idea is paralleled in The Matrix is easy enough to sort out. The "Empire" is the Matrix, created by the AIs. The "real" world is of no interest to them, and they do not seek to dominate it. The hyperreal world of the Matrix is the only "territory" worth defending, which they do at all costs against the realist terrorists aboard the Nebuchadnezzar, who aim to destroy it.Today abstraction is no longer that of the map, the double, the mirror, or the concept. Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal. The territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it. It is nevertheless the map that precedes the territory - the precession of simulacra - that engenders the territory... It is the real, not the map, whose vestiges persist here and there in the deserts that are no longer those of the Empire, but ours. The desert of the real itself. (Baudrillard 1994a, 1)

Baudrillard and his work are referenced both in the film and in the original screenplay. His book of essays Simulacra & Simulation, and specifically its last essay, "On Nihilism," are featured in the film when Neo retrieves what appears to be a copy of the book, but which in fact is a hollowed-out hiding place for illegal computer disks (and thus a book-simulacrum) that he gives to some shady-looking characters who have come to his door. Also, in the original 1996 screenplay Morpheus tells Neo in the Construct: "You have been living inside Baudrillard's vision, inside the map, not the territory. This is Chicago as it exists today." As we have seen, the idea of a map as a simulacrum of a territory that no longer exists, is taken from the first page of Baudrillard's essay, "The Precession of Simulacra," a primary source for many of the ideas in this film. Here Baudrillard argues that the relationship between the real and their simulacra have changed over time. Once there was a reality that could be represented by copies or simulacra. Original manuscripts, paintings or sculptures had to be reproduced by hand, for example. The original object was real, and the simulacrum phony or counterfeit. Reality preceded its mapping or representation. In the second order of simulacra, that of mass production, real objects (such as toys, cars, or books) are mass produced. There is no original to which the copies can or cannot be fully "true." The original no longer precedes the copy; one copy is not more authentic than the other. We are currently living in the third order of simulacra, that of models and codes. Here the simulacra precede what they represent, becoming not only real, but more than real, or "hyperreal," because there is no reality left to map or counterfeit. Simulacra are formed from code, and bear no resemblance to any reality whatsoever. Hyperreal simulacra include images and products like Madonna, Coca Cola, and Nike that are reproduced by the millions and which are imprinted onto our consciousness via TV, film, and other forms of media. For Baudrillard, postmodernity has rejected the very notion of a "true copy," which represents something more real or authentic than itself. We are at a point in history where simulacra are more real (and have a greater impact) than the original code from which they were created.

The three orders of simulacra map on to the last three phases of what Baudrillard calls the "phases" of the image:

Such would be the successive phases of the image:

it is the reflection of a profound reality;

it masks and denatures a profound reality;

it masks the absence of a profound reality;

it has no relationship to any reality whatsoever: it is its own pure simulacrum.

In the first case, the image is a good appearance - representation is of the sacramental order. In the second, it is an evil appearance - it is of the order of maleficence. In the third it plays at being an appearance - it is of the order of sorcery. In the fourth it is no longer in the order of appearances, but of simulation. (Baudrillard 1994a, 6)

The last phase represent the third order of simulacra, which masks the fact that there is no reality left to simulate and whose simulations bear no resemblance to any reality whatsoever. Morpheus and the crew of the Nebuchadnezzar believe that the Matrix (a metaphor for our own technological and hyperreal world) masks and denatures a profound reality, from which "the dreamers" must be redeemed. Now it is high time to awake out of sleep: for now is our salvation nearer than when we believed (Romans 13:11). Cypher disagrees, arguing, along with Baudrillard, that there is no reality left to simulate, that the simulacra (of the Matrix) are more real than "the desert of the real,"and that there is no longer a God to distinguish between the true and the false. Baudrillard writes:

The transition from signs which dissimulate something to signs that dissimulate that there is nothing marks a decisive turning point. The first reflects a theology of truth and secrecy (to which the notion of ideology still belongs). The second inaugurates the era of simulacra and of simulation, in which there is no longer a God to recognize his own, no longer a Last Judgment to separate the false from the true, the real from its artificial resurrection, as everything is already dead and resurrected in advance. (Baudrillard 1994a, 6)

The Matrix simulates and resurrects a reality that once existed, but all of which remains on post-eco-holocaust earth are "vestiges that persist here and there in the deserts that no longer are those of the Empire.... The desert of the real itself." According to Cyper, this desert must be abandoned in favor of the oasis of the hyperreal. Ironically, Morpheus, like Cypher, struggles with the distinction between reality and hyperreality, describing reality as a set of electrical signals interpreted by the brain. In the Construct he asks Neo:

Morpeus: What is real? How do you define real? If you're talking about what you feel, what you can smell, what you taste and see, then real is simply electrical signals interpreted by the brain. (From the film)

Here we catch Morpheus in a contradiction. According to him, if the mind believes it, it is real, yet he argues that the Matrix is not real, but a dream. Nevertheless, it is quite possible to die in the Matrix, or in any computer simulation program, because the body and mind are inextricably co-dependent. The unstated conclusion seems to be that life in the Matrix is not unreal but hyperreal - i.e. more real than reality. The difference between reality and hyperreality is not that one is more "authentic" than the other, rather, hyperreality is controlled by the AIs, and therefore the minds that inhabit it are not free. This is Baudrillard's chief criticism of our hyperreal culture: we are controlled by a system of binary regulation, by a code, by a Matrix. Reality, on the other hand, allows the mind to think for itself (in theory at least). One of the interesting elements of this film is that this premise is called into question. It is very unclear that there is more freedom in "the desert of the real" than there is in the Matrix. Nevertheless, the control exercised over it by the AIs, and not its illusory nature, is what Morpheus objects to:

Morpheus: The Matrix is everywhere, it is all around us, even now in this very room. You can see it when you look out your window, or you turn on your television. You can feel it when you go to work, when you go to church, when you pay your taxes. It is the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth.

Neo: What truth?

Morpheus: That you are a slave, Neo. Like everyone else, you were born into bondage... born into a prison that you cannot smell or taste or touch. A prison for your mind. (From the film)

In the film the "desert of the real" is meant in at least two ways: in the context of Neo and Morpheus's visit to the devastated surface of the planet, the real is quite literally a "desert," dark and devoid of life. In a second sense, the fact that most human beings are plugged into the dreamworld of the Matrix suggests that they, too, live in a desert of the real, which is to say an oasis of the hyperreal. There is also a third sense in which the film is about the desert of the real. We can map the distinction between the Matrix and the "real" world of those who have escaped from it onto a similar differentiation in our own world and in our own day. On the one hand, most people live in cities, depending on corporations for their livelihood and a sense of meaning and purpose in their lives. They are the power supply of the industrial-military-entertainment complex. Their world is dominated by mass media and advertising from every imaginable source, especially television, computers, and other forms of technology, which permeate their lives and determine the scope of their choices. Mass media invades their most intimate moments, accompanying them into the most secret recesses of their homes. On the other hand, there is a small faction of people who, like the Unabomber Ted Kaczysnki, have "escaped" from this culture. They live off the land in isolation, having spurned technology. Such people remain "uninfected" by hyperreal culture, and claim to see reality as it "really" is. Their project is to awaken the slumbering masses by offering up terrorist resistance to hyperreality. Like Baudrillard, these Luddites argue that in the era of models and codes, which multiply themselves and control the world by a system of binary regulation. It seems as if there are differences and choices: Pepsi or Coke, Democrat or Republican, Nike or Addidas etc, but they are constructed by those in control of the master codes and means of production of our civilization. In this way the system reduces differences and opposition to itself, especially political opposition. It should be noted, however, that in pre-industrial societies, free of the hegemonic control exercised by modern forms of media, there are no such choices, raising the question: "Is one more free in a society undominated by media?" Cypher doesn't think so, which is why he chooses the world of succulent steak over that of thin gruel. In the Matrix, the "illusion" (if it can be called that) of freedom is so convincing that the AIs have encountered almost no resistance to it. The only way to dispute the rule exercised by a system that appears to offer unlimited freedom is by nihilistic terrorism. Neo and Trinity's rampages are in fact not just blood and guts action, the meat designed to distract the "watch dog of the mind," as Schuchardt argues. They are acts of nihilist terrorism, and the only way to combat the merchants of the hyperreal.

Nihilism is a concept inextricably associated with terrorism. It is the denial of any basis for knowledge or truth and a rejection

of customary beliefs. It is also the fanatic conviction that existing institutions must be destroyed to make way for a new and

more meaningful order. Morpheus and his crew, at least from the point of view of the AIs, are nihilist-terrorists, who believe

that there is no basis for knowledge or values accepted by mainstream culture. Like all terrorists, they literally think that the

denizens of mainstream culture (i.e. those living in the Matrix) are living in a dreamworld. It is no coincidence that

Baudrillard's essay "On Nihilism" is featured in the film. Baudrillard, too, would like to be a nihilist, to resist the hegemonic

order, to fight the power:

Nihilism is a concept inextricably associated with terrorism. It is the denial of any basis for knowledge or truth and a rejection

of customary beliefs. It is also the fanatic conviction that existing institutions must be destroyed to make way for a new and

more meaningful order. Morpheus and his crew, at least from the point of view of the AIs, are nihilist-terrorists, who believe

that there is no basis for knowledge or values accepted by mainstream culture. Like all terrorists, they literally think that the

denizens of mainstream culture (i.e. those living in the Matrix) are living in a dreamworld. It is no coincidence that

Baudrillard's essay "On Nihilism" is featured in the film. Baudrillard, too, would like to be a nihilist, to resist the hegemonic

order, to fight the power:

If being a nihilist, is carrying out, to the unbearable limit of hegemonic systems, this radical trait of derision and violence, this challenge that the system is summoned to answer through its own death, then I am a terrorist and nihilist in theory as the others are with their weapons. Theoretical violence, not truth, is the only resource left to us. (Baudrillard 1994c, 163)

However, it is no longer possible to resist the system terroristically, because the system itself is nihilistic, agreeing with those who would oppose it that there is no basis for truth or knowledge. As such, it incorporates terrorist resistance to itself, embracing it while erasing the value of human life. The more insistent the resistance, the more indifferent the system's reaction to it.

But such a sentiment is utopian. Because it would be beautiful to be a nihilist, if there were still a radicality - as it would be nice to be a terrorist, if death, including that of the terrorist still had meaning. But it is at this point where things become insoluble. Because to this active nihilism of radicality, the system opposes its own, the nihilism of neutralization. The system is itself nihilistic, in the sense that it has the power to pour everything, including what denies it, into indifference.

In this system, death itself shines by virtue of its absence...And this is the victory of the other nihilism, of the other terrorism, that of the system. (Baudrillard 1994c, 163)

This is the why Neo's victory over the Matrix, if there is such a victory, could only come about by utterly destroying it as a physical system - by annihilating the technological structure supporting the hyperreality of the Matrix.(6)

Conclusion

Baudrillard, like the Wachowskis, find the terrorist resistance to the system both noble and hopeless - even silly. This is why, in the original screenplay conclusion to the film, we see Neo flying away like Superman as a disbelieving child asks his mother whether people can really fly. Attempts to transcend the hyperreal are puerile, a fantasy for children, worthy of comic book characters. At the same time the possibility of such a transcendence inspires us with awe and a renewed hope for the existence of something solid behind the images. Significantly, Neo can be seen as a simulacrum of Jesus Christ and Superman - nothing about him is original or true. If there were still a reality left to represent, he would have to be described as a fake, a phoney, and a false prophet. From the point of view of Baudrillard's bleak nihilism, the true prophet would be Cypher, who bears the "secret message" of the film: "You see, the truth, the real truth is that the war is over. It's been over for a long time. And guess what? We lost! Did you hear that - we lost the war." Since there is no reality left to simulate, Neo is not a fake - he is as hyperreal as the hyperreality he opposes. Like Don Quixote who believes that he lives in an earlier era of knights and damsels, of honor and courtly love, Neo is both a freedom fighter and a terrorist, good and evil, noble and ridiculous. But he is not outside the system, he is embraced and engulfed by it because the reality he is fighting for no longer exists - it is a utopia, an ancient legend.

The imaginary was the alibi of the real in a world dominated by the reality principle. Today, it is the real that has become the alibi of the model, in a world controlled by the principle of simulation. And paradoxically, it is the real that has become our true utopia- but a utopia that is no longer in the realm of the possible, that can only be dreamt as one would dream of a lost object. (Baudrillard 1994b, 122-123)

In short, to fight the Matrix one has to leave the hyperreal far behind, to rigorously think oneself outside it, and then find a way to physically destroy it. Baudrillard, something of a pessimist, doesn't seem to think that this is remotely possible. Whether we take seriously Neo's closing message that "anything is possible" depends on whether we believe that the map of the hyperreal has entirely eclipsed the territory of contemporary culture. If it has, then we would be well advised to order a big juicy steak, and enjoy the ride. If not, we can, like Neo, choose to fight the power.

Raw, metaphysically bold/Never followed a code

Still droppin' a load/Droppin' a bomb...

Brain game, intellectual Vietnam/Move as a team, never move alone

But/Welcome to the terrordome.

Chuck D., lyrical terrorist/Public Enemy on Fear of a Black Planet

Bibliography

The Matrix (1999). Written and Directed by Larry and Andy Wachowski. Warner Brothers.

Schuchardt, Read Mercer (2002). "Parable, Experience, Question, Answer": http://www.metaphilm.com/philms/matrix1.html. This essay was originally posted in 1999 on http://www.cleave.com.

The Official Site: http://whatisthematrix.warnerbros.com/

Dew's Matrix Fan Page (point-form summaries of a variety of themes in the film, along with a short essay on how the film compares to Plato's Allegory of the Cave): http://www.geocities.com/hollywood/theater/9175/neo/home.html

"The Matrix as Messiah Movie" (1999-2002): http://www.awesomehouse.com/matrix/parallels.html

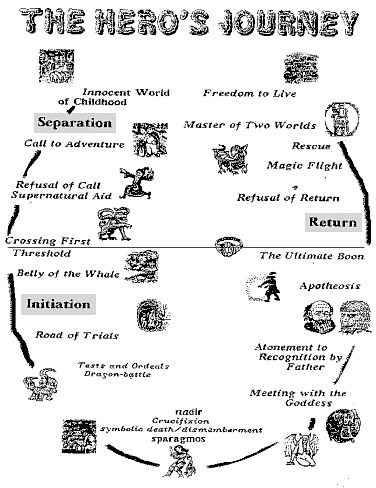

Brennan, Kristen (2001). "Star Wars Origins" (analyses Star Wars and The Matrix as instances of the Hero's Journey): http://www.jitterbug.com/origins/myth.html

Baudrillard, Jean (1994a). "The Precession of the Simulacra." Simulacra and Simulation. Trans. Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Baudrillard, Jean (1994b). "Simulacra and Science Fiction." Simulacra and Simulation. Trans. Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Baudrillard, Jean (1994c). "On Nihilism." Simulacra and Simulation. Trans. Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Descartes, René (1968). The Meditations. In Discourse on Method and The Meditations. Trans. F. E. Sutcliffe. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Appendix: The Matrix as a Hero's Journey

Appendix: The Matrix as a Hero's Journey

As a number of interpreters have pointed out, there is another, meta-philosophical answer to the question "what is the Matrix?": the film tells the story of the quest of our techno-hero Neo in a self-conscious recounting of the "monomyth" found in most ancient hero sagas. Neo can be read as yet another incarnation Joseph Campbell's Hero with a Thousand Faces, a modern Gilgamesh, Odysseus, Arthur or Beowulf. The following stages from the Hero's Journey can be fairly clearly discerned in The Matrix, although the order of Campbell's steps isn't adhered to rigorously in the film:

I. DEPARTURE

II. INITIATION

III. RETURN

Yet what makes The Matrix unique is not the fact that it echoes Campbell's monomyth, which can be seen a number of other films (e.g. the original Star Wars trilogy and Oh Brother, Where Are Thou?), but that it offers the rich interweave of philosophical interpretations discussed in this paper.

Notes

1. Evidence that this tripartite interpretation of the film comes close to the philosophical intent of the Wachowski Brothers can be found

in the scene where we first meet Neo. It takes place in his apartment within the Matrix. After Trinity startles Neo with a message on his

computer about the Matrix, Neo's friend Choi knocks at the door . He is surrounded by a group of people, including his alluring

girlfriend Dujour. Choi buys some illegal computer disks which Neo has were hidden in a copy of Baudrillard's Simulacra and

Simulation. He thanks Neo: "Hallelujah. You're my savior, man! My own personal Jesus Christ!". Seconds later, after Choi remarks

that Neo looks a little whiter than usual, Neo asks him "You ever have that feeling where you're not sure if you're awake or still

dreaming?" In short, a book full of computer simulations, a personal savior, and Descartes' basic metaphysical question about the

reality of the world, all within one minute of screen time.

2. See the Appendix for a fourth interpretation of the film that runs parallel to those given in this paper.

3. We quote from the original 1996 screenplay since it illustrates Cypher's view of the relative values of the Matrix and the real world

more clearly than does the moderately revised version of the scene presented in the film.

4. There is another scene in the original 1996 screenplay that makes this point clear. When Neo's friend Anthony comes to ask him to do

some hacking to release his car from a Denver boot installed by the police (in the final screenplay his friend is name Choi, who comes

over to buy illegal software), Neo is successful, and the cops arrive to do so. They "watch from the window as the cops silently,

robotically, climb into their van," Anthony remarking, "Look at 'em. Automatons. Don't think about what they're doing or why.

Computer tells 'em what to do and they do it."

5. In the fight between Smith and Neo in the subway station toward the end of the film, the theme of fate and free will arises yet again

when Smith, hearing the rapidly approaching train, asks Neo if he knows what that it. Answering his own question, he says "That is the

sound of inevitability... It is the sound of your death." Fortunately for him, Neo is an advocate of free will, so he leaps in the air and

does a back flip off the tracks, thus exchanging his own dire fate with Smith's more palatable one.

6. Again, this is a conclusion similar to that reached by Kaczynski in his manifesto "Industrial Society and its Future."