The Post-Ideological

Hero: Comic Books Go to

Extended Director’s Cut by Doug Mann, 2008

1. The

Films starring comic book heroes

have been big box office at least since Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman, which appeared the same year the Berlin Wall fell,

heralding the end of the Soviet Empire and thus the Cold War. Since the turn of

the millennium there has been a steady stream of blockbusters based on comic

books, from X-Men of 2000 to The Dark Knight in 2008, with yet more in

the wings. Most of them star Marvel Comics characters. An obvious question

emerges: even though comic book superheros have been

around since Superman’s first appearance in 1938, and have appeared in

animation and movie serials since the 1940s, why did it take until the 1990s

for them to appear in serious cinematic narratives? And now that

One curious thing about this new

brand of comic book hero, making him ideally suited to our own period of

history, is his post-ideological nature. He no longer fights grand ideological

struggles against

One curious thing about this new

brand of comic book hero, making him ideally suited to our own period of

history, is his post-ideological nature. He no longer fights grand ideological

struggles against

So why the hero at all, whether

ideological or not? Joseph Campbell has convincingly shown us in The Hero with a Thousand Faces how hundreds

of ancient myths and epic tales feature the same monomythic

hero on the same three-stage seventeen-part journey. From Odysseus to Luke

Skywalker, the classical hero gets a message, leaves home, enters the belly of

the whale, fights many battles, then returns home with

a fabulous prize. Jewett and Lawrence later showed us how the heroes of

American popular culture repeat over and over again their own tightly

structured adventure. So heroes are everywhere, from ancient Sumerian myth and classical literature to modern cinema and professional

sports. Why? Heroes are projections of the hopes and fears of the cultures

which create and worship them. They express a desire for power over the self

and others, the hope for a saviour to protect us against dangerous enemies.

Little boys don’t dress up as bureaucrats on Halloween, with mini-briefcases

and rubber stamps in their hands: they become Superman, Batman or Spider-Man.

One needs no ghost of Nietzsche coming from the grave to tell us that heroes

are avatars of personal power and of social salvation. They are Hector and

Achilles, Boudicca and Arthur, Luke and Han, dark knights and supermen. They

save us, or inspire us to save ourselves.

When Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

re-booted Marvel Comics with a new stable of superheros

in the early 1960s, thus inaugurating the Silver Age of comics, they created a

series of characters who by and large avoided the burning political issues of

the day. The Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, Daredevil, and the Hulk rarely

addressed such issues as the civil rights and anti-war movements, the war in

Part of this absence of serious

comics-based films is connected to the limitations of special effects until

well into the 1980s: after all, even George Lucas’s cutting edge Star Wars (1977) relied almost entirely

on hand-crafted models and rear-screen projection for its dramatic space battle

sequences. Yet on a deeper level it can be explained by the political-cultural

landscape of the entire postwar period until 1989: cinematic heroes like Luke

Skywalker and Rambo did have

ideological causes to fight for, and audiences expected to see them fighting

these battles. The fact that Rambo III (1988)

finds Sylvester Stallone’s hero in

These

comic book films are not only post-ideological, but also postmodern in a number

of key ways:

$ (1) They are a case of a hyperreal

media culture where images precede reality, of what Jean Baudrillard

called the Third Order of the Simulacrum;

$ (2) They

symbolize the breakdown of high cinematic art (if this ever existed!) and its

mixture with what was once considered a very low brow medium, comics;

$ (3) They

show us an aesthetic where style can all too often triumph over substance -

after all, the heros and villains of comic books are

fantastic beings wearing colourful uniforms showing us a division between good

and evil that is usually quite Manichean;

$ (4) They

involve the uniquely postmodern impulses of pastiche and recycling, in this

case the recycling of comic-book narratives in cinematic form,

$ (5) And

in keeping with their post-ideological nature, they symbolize Lyotard’s very definition of the postmodern condition, our

incredulity toward meta-narratives.[4]

The coincidence of

post-ideological politics and postmodern culture is by no means accidental:

after all, in an age where capitalist democracies reign supreme, alternate

political meta-narratives can’t be taken seriously. Our incredulity toward them

in the Western world is connected in part to their lack of global power. A

possible threat to capitalist democracy comes from Islamic fundamentalism,

whose terrorist arm has certainly caused much death and destruction throughout

the world of late. Yet the danger of a Islamic

terrorism is hardly existential (i.e. as long as they don’t have nuclear

weapons), while the appeal of the sort of Moslem theocracies that Al Quaeda and the Taliban seek to establish is almost zero in

the West. No propaganda war is needed to defeat the vague political ideology of

Islamic fundamentalism in the West, while such propaganda campaign is almost

pointless in

Liberal Hollywood seems to

recognize the ethnic and cultural nature of Islamic fundamentalism. Due to

politically correct fears about alienating Arabs, Persians and other Moslem

nations, Hollywood has avoided ethnic stereotyping of villains in films about terrorism

to the point where realism is thrown out the door (unlike American action films

from the 1940s to the 1970s, which had no problem stereotyping Germans or

Russians as monomaniacal ideological enemies). A classic case of such a refusal

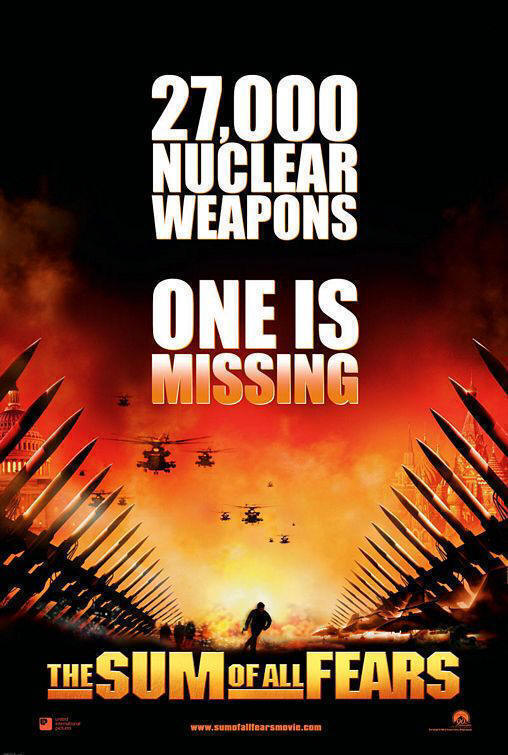

to replace Germans and Russians with Arabs as the villains du jour can be seen in Phil Alden Robinson’s 2002 film The Sum of All Fears, based on Tom

Clancy’s thriller about a group of Al Quaeda

terrorists who find an Israeli nuclear bomb, transport it to the US, then detonate

it. In a bizarre case of bad writing, Clancy’s Moslem terrorists become a

German-Russian secret cabal of powerful business and political leaders seeking

to foment a nuclear war between Russia and America, in the wake of which a

Fourth Reich of fascist regimes will take power in the West. They do manage to

blow up

Liberal Hollywood seems to

recognize the ethnic and cultural nature of Islamic fundamentalism. Due to

politically correct fears about alienating Arabs, Persians and other Moslem

nations, Hollywood has avoided ethnic stereotyping of villains in films about terrorism

to the point where realism is thrown out the door (unlike American action films

from the 1940s to the 1970s, which had no problem stereotyping Germans or

Russians as monomaniacal ideological enemies). A classic case of such a refusal

to replace Germans and Russians with Arabs as the villains du jour can be seen in Phil Alden Robinson’s 2002 film The Sum of All Fears, based on Tom

Clancy’s thriller about a group of Al Quaeda

terrorists who find an Israeli nuclear bomb, transport it to the US, then detonate

it. In a bizarre case of bad writing, Clancy’s Moslem terrorists become a

German-Russian secret cabal of powerful business and political leaders seeking

to foment a nuclear war between Russia and America, in the wake of which a

Fourth Reich of fascist regimes will take power in the West. They do manage to

blow up

If asked “when it all changed” and

the post-ideological world-view replaced the ideological struggle of the Cold

War, we can point to the period 1988-1991. A cinematic metaphor comes

immediately to mind: John McTiernans’ 1988 film Die Hard, wherein Bruce Willis’s

hard-as-nails

This essay will offer an overview

of the history of the use of comic book heroes in film and to a lesser degree

television to chart the emergence of the post-ideological hero, showing how he

came out of the unique political and culture landscape in the West after 1989.

2. Other Theories about Comic Book Films

Although hundreds of reviews of

the second wave of superhero blockbuster films have been published since 2000,

there is precious little scholarly reflection on the general cultural meaning

of these blockbusters. One thing is clear from the most cursory glance at these

reviews: major studios such as Fox,

Three

general types of explanation for the popularity of comic book blockbusters come

out of the literature - though only the first explanation specifically

addresses the post-2000 films as a collective phenomenon. First comes the

“marketing” theory put forward by McAllister, Gordon and Jancovich

(2006). They argue that comic art has been adapted to two very different types

of films: the “popcorn” blockbuster superhero film, with big budgets, big

stars, big distribution and big profits; and “art house” film adaptations of

graphic novels such as V for Vendetta,

American Splendour and

Three

general types of explanation for the popularity of comic book blockbusters come

out of the literature - though only the first explanation specifically

addresses the post-2000 films as a collective phenomenon. First comes the

“marketing” theory put forward by McAllister, Gordon and Jancovich

(2006). They argue that comic art has been adapted to two very different types

of films: the “popcorn” blockbuster superhero film, with big budgets, big

stars, big distribution and big profits; and “art house” film adaptations of

graphic novels such as V for Vendetta,

American Splendour and

Yet

the “marketing” explanation is dubious as best: for one thing, it hardly

explains the move away from historical blockbusters (think of Ben-Hur and Lawrence of Arabia) that dominated

American screens in the 1950s and 1960s, nor why comics-based films have more

recently outpaced science-fiction blockbusters such as Independence Day. Certainly blockbusters have always been popular,

though they sometimes crash and burn as (think of Heaven’s Gate and Godzilla). Yet

why have a combination of comic book movies and fantasy films such as Harry Potter, Pirates of the Carribean and The

Lord of the Rings run up such big box office over the last decade?[5]

Further, are the characters and plots of these blockbusters always simplistic?

Sometimes yes; though the two most successful comic-book blockbusters of 2008, Iron Man and The Dark Knight, feature both strong character development and

complex plots, especially the latter. In the end the “marketing” explanation is

for the most part a “shell” hypothesis, tautologically reminding us of

something we already know: that a lot of people like big-budgeted comic book

films.

Second

comes a number of “spiritual” explanations. Niall

Richardson (2004: 695) sees Spider-Man (2002)

as a Christian parable where Peter Parker must atone for this sinful flesh for

lusting after Mary Jane and accidentally letting his Uncle Ben die by

converting his general sense of shame into an expiable guilt. The Green Goblin

stands in for the devil, quoting scripture, tempting Spidey

with power and trying to force him to make the grim choice between saving a

trolley car of children or an imperilled Mary Jane (he manages to do both).

Admittedly,

A

related “spiritual” explanation is the much more comprehensive position on

American popular culture in general found in Jewett and Lawrence’s The American Monomyth

(1973). Their view is that deeply embedded in American popular culture is a

monomyth at odds with the classical monomyth explored by Joseph Campbell. This American version

tells the following story:

A community in a harmonious paradise is

threatened by evil: normal institutions fail to contend with this threat: a

selfless superhero emerges to renounce temptations and carry out a redemptive

task: aided by fate, his decisive victory restores the community to its paradisical condition; the superhero then recedes into

obscurity. (Jewett and Lawrence xx)

They go on to argue that the supersaviors of the American monomyth

act as substitute Christ figures with divine, redemptive powers in a culture

where belief in the actual Jesus Christ has been eroded by scientific

rationalism. They offer American culture a “mythic massage,” relaxing it

sufficiently to believe that extra-democratic heros

will save the day in times of crisis should they be needed (xx).

Superhero

films do administer a mythic massage, though not especially the pseudo-Christian

one hinted at by Jewett and Lawrence. Some of the superhero stories fit the

American monomyth quite well, notably the one they

focus on, Superman. Yet other key superhero narratives are either ambiguous

cases of the American monomyth at best (e.g. the

X-Men) or simply don’t fit it at all (the Hulk, Iron Man, Batman). The fact

that in the last scene of Iron Man (2008)

Tony Stark starkly proclaims, “I am Iron Man!” gives away the monomythic

game: he’s out of the secret identity closet, and can’t get back in. As I write

this Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008)

has just broken first-weekend box office records across

A

third explanation for the popularity of comic-book films of a sociological

nature comes indirectly from Matthew Wolf-Meyer’s analysis of the hostility to

utopian narratives amongst comics fans. Wolf-Meyer (511) argues that comic book

readers are a conservative lot who ironically cherish their “subcultural position of difference” within consumer

capitalism: they are against its hegemony, yet sure enjoy the comics it

provides them with, even if that system creates social injustice. As a result,

they favour their superheroes fighting an endless array of super-villains

rather than changing society for the better and thus ending their own monthly

usefulness.[6] Comics fans know the

majority don’t understand them, and that’s the way they like it. Stories about

utopia achieved are out of the question:

...if the

discourse were to alter significantly to allow such things as utopian

narratives then fandom, and its position of difference, would collapse,

eradicating difference and solidifying comic book fans as typical citizens

within hegemonic capitalism, deprived of their discourse and their difference,

maintaining only their conservative ideology, trivialized and commodified within the constraints of hegemony... Hence,

comic book fans trade “utopian” narratives for the utopia of a subculture standing

against hegemonic capitalism. (513-514)

Wolf-Meyer’s

theory does seem to explain why comic book fans accept the conservative status

quo in the alternative universes where their superheroes live - though a simple

economic explanation, that comic book publishers want to keep publishing their

most popular superhero titles so they avoid creating utopian “end of history”

scenarios, would suffice. One could try

to apply his theory to comic book films. Yet there’s no indication that the

majority of non-comic book reading audience members at superhero films,

probably 80-90% of the audience - judging by monthly comics sales - are

anti-capitalist rebels, or members of any subculture at all. In addition, most

superhero films take place outside of the decades-long continuities of the main

DC and Marvel characters: they start over from the beginning (e.g. Batman, Spider-Man, The X-Men), and feel

free to kill off secondary characters and villains for dramatic effect (e.g.

the Joker, the Green Goblin, Harvey Dent). So these films are partly free from

the seriality and endless repetitions that many comics fans at least tolerate, if not treasure. Within a

single “reboot” (e.g. the four Batman films between 1989 and 1997 or the

Spider-Man trilogy of 2002-2007) utopia

can be achieved - though admittedly rarely is - without either disrupting

any cinematic “continuity” or alienating mainstream popcorn movie fans.

In

the end, all the meta-theories that seek to explain either directly or

indirectly the post-1989 popularity of superhero blockbusters are either

tautological or partial theories, missing key elements or overlooking key

films. Let’s now return to comic books’ Golden Age and review the history of

the interaction between the print and cinematic versions of the superhero to

see how the post-ideological simulacral hero has

emerged.

3. The DC Superheros: Superman and Batman

3. The DC Superheros: Superman and Batman

The most famous superhero is probably DC Comics’ Superman, who made his first appearance in Action Comics in 1938, getting his own book a year later. The Man of Steel, a refugee of the planet Krypton, is almost invincible: he can only be defeated by the element kryptonite, a fragment of his home world. He can fly, lift huge weights, deflect bullets from his chest, and jump tall buildings with a single bound. He is the all-American hero.

Superman

crossed over from the comic book page to film and television soon after his

first appearance in 1938 in Action

Comics, and has had an almost continuous existence outside these pages.

George Reeves starred as Superman in Adventures

of Superman, a TV series based on the comic-book character broadcast from

1952-1957. Several other series concerning Superman have aired, including Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of

Superman (1993-1997), which made Teri Hatcher a minor celebrity for playing

the role of Lois Lane, and Smallville, on the

air since 2001, about the young Clark Kent. The characters on this show take

themselves rather seriously - it’s part superhero

story, part teen drama. There have also been a number of cartoon versions going

back to the package of seventeen shorts created by Max and Dave Fleischer for

Bryan

Singer’s 2006 film Superman Returns pictures

him as a Christ-like redeemer straight out of the American monomyth,

with the voice of Marlon Brando substituting for the voice of God. In this

enthusiastic adventure the Man of Steel once again battles Lex

Luthor. Singer’s Christian metaphysic is thinly

disguised at best. After being clobbered by Lex

Luther, we see Superman fly into the heavens to renew his Sun-powered energy as

he spreads his arms in a Christlike pose and a choir

of angels sings on the soundtrack. He then plays the role of humanity’s

saviour, lifting Lex’s expanding kryptonite

island into space, then falling back to Earth in another Christ-like

pose. He hovers near death in a Metropolis hospital for days, but is reborn,

presumably healed by the Platonic love of

Superman

is comparatively stiff compared to most of the other superheros,

a do-gooder without emotional depth. He doesn’t have the personal problems of

the Marvel superheros, other than protecting his

secret identity from nosey reporters. In a lot of ways he’s more like the

heroes of 1930s serials than later comic book characters - he’s not a model for

real people and doesn’t care about social problems.[7]

In fact, he’s not even human, but a refugee from the planet Krypton. He harkens

back to an earlier age of science fiction and comic books, when the heroes were

lily white, and the villains dark and nefarious. The films certainly illustrate

the way that

Batman

also goes back to the innocence of the pre-WWII period in American comics,

making his first appearance in Detective Comics in 1939, getting his own book

in 1940. His adventures were turned into a set of serial shorts in 1943

(Superman had to wait until 1948 for a serial adaptation). Batman became part

of kitschy pop culture in the 1960s with the tongue-in-cheek TV version of the

comic book starring Adam West as the main character. Batman dresses in a bat

costume made of tights and boots, rides around in his batmobile,

and uses his brains and all sorts of neat gadgets to defeat enemies like the

Penguin, the Riddler, and Catwoman.

In the TV series he is shown with his partner Robin (Burt Ward) the Boy Wonder

in place right from the start. The fights are corny, adorned with cartoon

bubbles with “zowee” and “kaboom.”

The best written episodes, especially those by Lorenzo Semple

Jr., are full of sly humour and visual puns. This incarnation

of Batman never took itself too seriously - in its own way it was part of the

pop art movement lead by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein.

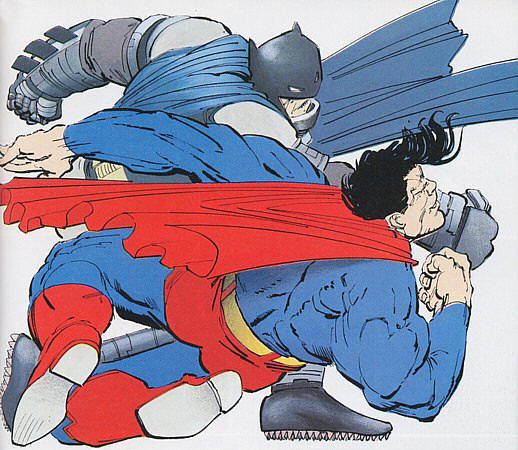

The

polar opposite of the campy 1966-1968 TV series was Tim Burton’s evocation of

the later, much grittier version of Batman based on the 1986 The Dark Knight Returns series of DC

comics written and drawn by Frank Miller (later published as a popular graphic

novel).

The

first sequel was Batman Returns (1992),

with

The

faltering Batman franchise called for a cinematic re-envisioning, which it got with Christopher

Nolan’s more dark, serious and camp-free version of the caped crusader in his

2005 film Batman Begins. In one scene

we actually see Bruce Wayne lying in bed battered and bruised after a battle,

unimaginable in the Val Kilmer and George Clooney Batman films. Also, Nolan

used very few CGI shots in his version, adding to its air of naturalism.

Interestingly, Nolan featured mainly British and Irish actors in key roles:

Christian Bale as Batman, Gary Oldam as Commissioner

Gordon, Michael Cain as Alfred the Butler, Cillian

Murphy as Dr. Jonathan Crane AKA The Scarecrow, Tom Wilkinson as Carmine Falcone and Liam Neeson as Henri Ducard. One presumes that his goal was to add some gravitas to an otherwise lighthearted

filmic heritage for

In

Nolan’s followup The

Dark Night (2008) we see the ultimate in grim noir realism applied to the Batman mythos.

In this long (two and a half hours) and complex film, we witness a triadic

struggle between reformers in the Gotham City administration and police force

led by D.A. Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart) and Lieutenant (later Commissioner) Jim

Gordon (Gary Oldham); Mafia-style gangsters led by Salvatore Marone (Eric Roberts), who have bribed or threatened a

number of cops into betraying the cause of justice; and the demented Joker

(Heath Ledger) and his ever-changing gang, true agents of chaos. Batman is

obviously allied to the good cops and later to Dent, though throughout the

movie has crises of faith about his role as populist hero: we see several

“copycat” Batmans injured or killed as they try to

battle crime. There is no ideology at all in Nolan’s film: Batman’s main goal

is to stop the Joker from killing innocents, which the clown prince of crime

does with glee, supported by an existential nihilist philosophy that sees the

average human being as weak and selfish. There’s no external enemy or

threatening belief system in The Dark

Knight: Batman’s goal is to battle chaos and death itself - in two scenes

he refuses to kill the Joker, though he could easily do so, once by running him

over with his batcycle, the other by dropping him off

a building. This battle is punctuated by the fact that death is all around him:

a raft of minor characters and two major ones actually perish when caught in

the Joker’s maelstrom. Christian Bale’s Bruce Wayne/Batman has his own inner

demons, yet they pale in comparison to the Joker’s psychosis. There’s no

explicit reference to fascism, capitalism, communism or Islamism in this film:

it’s about revenge, madness, and survival. The

Dark Knight perfects Batman’s status as DC’s post-ideological hero par excellence: he’s both insider and

outcast, both criminal and defender of justice.

Batman

is the perfect post-Cold War hero: his primary motivation for fighting crime is

revenge over his parents’ death at the hands of criminals. There’s no grand

meta-narrative to explain Batman’s raison

d’etre: he is an instrument of personal

vengeance. He fights evil, though this evil isn’t ideologically motivated:

instead, it consists of a coterie of colourful

criminally insane enemies such as The Joker, Two Face and Poison Ivy. Arkham Asylum replaces the penitentary

as the usual place of residence for Batman’s enemies for good reason: their motivation for being criminals are their various

psychopathologies.

In addition, the Batman franchise is a

powerful example of TV and film recycling comic book culture. We can also see

it as an example of the breakdown of high art and the penetration of pop

culture into mass consciousness - more people know and take seriously Batman

than characters from the novels of Dickens, Dostoevsky or Jane Austen. He’s as

famous as any poet or composer, his image and story instantly recognizable by

most people under the influence of American mass culture. Yet there is a shadow

of the old good-versus-evil meta-narrative in the Batman stories, even if the

Dark Knight’s motives for fighting crime have more to do with revenge for the

death of his parents than any high-minded concern with truth and justice. This

is certainly ambiguous, with one bat foot in modernism, and the other in the

postmodern. To be continued.

4. The Marvel Superheros: The X-Men, Spider-Man, Daredevil, the Hulk and Iron Man

Though

the Batman films from 1989 on are an interesting prologue to the emergence of a

new type of simulated heroism, it wasn’t until the new millennium that we see a

marvellous (pun intended) explosion of

post-ideological comic book heros on the big screen. X-Men (2000), which stars

the distinguished British actors Patrick Stewart as Dr. Xavier and Ian McKellan as the villain Magneto, is the movie version of

the Marvel comic book series The Uncanny

X-Men, which dates back to 1963. The X-Men are mutants, human beings who

have been given special powers due to genetic mutations. They share some of the

characteristics of all Marvel superheros: they have

ordinary lives when not being superheros, are

misunderstood by the masses, and have the same personal problems as everyone

else, magnified times ten due to the heavy burdens of super-herodom.

The

X-Men include Cyclops, who shoots a powerful ray from his eyes (he is thus

stuck wearing sunglasses when not in his crime-fighting gear), Storm, who can

control the weather, and Jean Grey, who has telekinetic powers. They are lead

by Dr. X, played by Patrick Stewart, who is crippled but has tremendous mental

powers. A late addition to the group is the popular character Wolverine (Hugh Jackman), a Canadian who sprouts claws from his hands and

has a bad attitude toward authority. The interesting thing about the film is

that there are also “bad” mutants who don’t trust ordinary humans. Yet this is

for good reason - American politicians led by Senator Kelly (a postmodern

stand-in for Joseph McCarthy) are seen trying to pass a law registering

mutants, if not imprisoning or banishing them as a dangerous “alien” influence.

In a flashback at the start of the film we see the leader of the “evil” mutants

Magneto as a young boy in a Nazi concentration camp, driving home the supposed

central theme of the movie: the wrongness of discrimination against groups of

people based on biological difference.[9]

However, this theme is old hat in Hollywood, being played out time and time

again from the anti-Nazi films of the 1940s from Warner Brothers and other

American filmmakers to Spielberg’s Schindler’s

List (1993) and Amistad (1997),

that it is in danger of becoming hackneyed. Yet this old-fashioned liberal

homily is played against the backdrop of a virtual world populated by

The

X-Men include Cyclops, who shoots a powerful ray from his eyes (he is thus

stuck wearing sunglasses when not in his crime-fighting gear), Storm, who can

control the weather, and Jean Grey, who has telekinetic powers. They are lead

by Dr. X, played by Patrick Stewart, who is crippled but has tremendous mental

powers. A late addition to the group is the popular character Wolverine (Hugh Jackman), a Canadian who sprouts claws from his hands and

has a bad attitude toward authority. The interesting thing about the film is

that there are also “bad” mutants who don’t trust ordinary humans. Yet this is

for good reason - American politicians led by Senator Kelly (a postmodern

stand-in for Joseph McCarthy) are seen trying to pass a law registering

mutants, if not imprisoning or banishing them as a dangerous “alien” influence.

In a flashback at the start of the film we see the leader of the “evil” mutants

Magneto as a young boy in a Nazi concentration camp, driving home the supposed

central theme of the movie: the wrongness of discrimination against groups of

people based on biological difference.[9]

However, this theme is old hat in Hollywood, being played out time and time

again from the anti-Nazi films of the 1940s from Warner Brothers and other

American filmmakers to Spielberg’s Schindler’s

List (1993) and Amistad (1997),

that it is in danger of becoming hackneyed. Yet this old-fashioned liberal

homily is played against the backdrop of a virtual world populated by

We

see impressive special effects in the film: the evil mutant Mystique (Rebecca Romijn-Stamos) changes her physical appearance several times;

her boss Magneto levitates through the air and lifts police cars, guns, and

other metal objects with the power of his mind; while Storm (

Overall,

the X-Men are vaguely ideological at best, in the sense that in their various

incarnations in comics and film they have fought against prejudice based on

biological difference. The problem is that so do Magneto and his merry band of

“evil” mutants: both sides want to improve the plight of mutants,

it’s just a question of how to accomplish this. Yet at its core the

anti-discrimination theme in the X-Men corpus is rather hollow: after all,

there are no mutants, good or evil,

in the real world, while the mapping of these fictional mutants onto any actual

minority groups is a slippery process at best. The process of seeing the

mutants in the world of the X-Men as symbols of groups of people in the

non-comic book world is fraught with difficulty, in part due to the internal contraditions in the X-corpus. In the end, the X-Men are

simulated post-ideological heros

just as much as Magneto, Toad and Mystique are simulated post-ideological

villains, with some pretense to real world political

significance.

Spider-Man

is one of the most famous of the Marvel superheros.

He is in the Marvel mould of being an ordinary guy thrust into the role of

being a hero by a freak accident - he was bitten by a radioactive spider, and

as a result gained extraordinary strength, the ability to climb walls, and a sixth sense that is aware of danger before it

happens. He develops a device that shoots sticky webs from his hand across

large distances, hence his nickname “the webslinger.”

His motives are suspected by J. Jonah Jameson, the publisher of a tabloid

newspaper that ironically Peter Parker, the real man behind the mask, works for

as a freelance photographer. The spectacularly drawn special editions of The Amazing Spider-Man comic book drawn

by Todd McFarlane in the late 1980s and early 1990s helped to revive the

character. There was also a crudely drawn cartoon TV series dating from

1967-1970 directed in part by Ralph Bakshi that

spawned the theme song for Spiderman: “Spiderman, Spiderman, Does whatever a

spider can...,” of which the Ramones recorded a delightful cover.

Spider-Man

is one of the most famous of the Marvel superheros.

He is in the Marvel mould of being an ordinary guy thrust into the role of

being a hero by a freak accident - he was bitten by a radioactive spider, and

as a result gained extraordinary strength, the ability to climb walls, and a sixth sense that is aware of danger before it

happens. He develops a device that shoots sticky webs from his hand across

large distances, hence his nickname “the webslinger.”

His motives are suspected by J. Jonah Jameson, the publisher of a tabloid

newspaper that ironically Peter Parker, the real man behind the mask, works for

as a freelance photographer. The spectacularly drawn special editions of The Amazing Spider-Man comic book drawn

by Todd McFarlane in the late 1980s and early 1990s helped to revive the

character. There was also a crudely drawn cartoon TV series dating from

1967-1970 directed in part by Ralph Bakshi that

spawned the theme song for Spiderman: “Spiderman, Spiderman, Does whatever a

spider can...,” of which the Ramones recorded a delightful cover.

The

film version from 2002 uses spectacular special effects of an all-virtual CGI

Spiderman swinging from building to building as he does in the comic books,

which would have been technically impossible a couple of decades ago. It’s

directed by Sam Raimi. His foe is the Green Goblin, played

with verve by Willem Dafoe, a millionaire deranged by his own experimental

nerve gas. In it we are given a glance of insight into Peter Parker’s teenage

angst - just enough to make the film true to the spirit of the comics.

Spider-Man was an existential hero right from his origin in Amazing Fantasy #15. Even in his early

days in the mid-60s he rarely fought for abstract ideas or national causes, but

out of a very personal sense of existential responsibility fuelled by the death

of his Uncle Ben at the hands of a theif who Peter

Parker for selfish reasons let escape just before the murder. The film

emphasizes Spider-Man’s existentialist origins by having the spirit of Uncle

Ben repeat Spidey’s famous mantra in a voiceover:

“with great power goes great responsiblity.”

Spider-Man’s loyalties aren’t to his nation or to any given ideology, but to a

very personal (and thus very contingent) sense of existential responsibility.

In

2004 a successful sequel appeared, Spider-Man

2, in which Spidey fights Dr. Octopus. Once again

his enemy is a deranged scientist who is tragically driven insane by his own

invention. Peter Parker is still tormented by problems in his school, love and

personal lives, with Mary Jane set to marry someone else and J. Jonah Jameson’s

Daily Bugle trumpeting the idea that

Spider-Man is the true menace to society.

The uneven Spider-Man 3 appeared

in 2007, featuring Spidey’s battles with three

villains: the Sandman, Venom, and the son of the Green Goblin. Peter faces the

real danger of losing his true self when a black alien

goo enhances his powers, making him arrogant and overbearing. Yet he manages to

triumph over these threats to his existential integrity, at the end of the film

offering these thoughts to the audience in a voice-over meditation on the death

of Harry Osborn:

Whatever

comes our way, whatever battle we have raging inside us, we always have a

choice. My friend Harry taught me that. He chose to be the best of himself.

It’s the choices that make us who we are, and we can always choose to do what’s

right.

In summary, Spider-Man was

envisioned by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko as an

existential hero who had to daily face both his own inner demons (e.g. his

responsibility for the death of his Uncle Ben and his doubts about being a

crime fighter) and problems with personal relationships (e.g. his sick Aunt

May, his chronic money shortage, and his hapless love life). Sam Raimi’s films capture the existential spirit of the classic

Spider-Man stories of the Silver Age of comics quite well. In doing so they

make manifest what was latent in the early Spider-Man comics: his status as a

post-ideological hero.[10]

Daredevil

is a blind lawyer who fights crime mainly with his radiation-enhanced strength

and extrasensory awareness that’s a bit like radar. He’s a sort of poor man’s

Spider-Man. Certainly the vulnerability of a blind man to enemies is a far cry

from Superman’s near invincibility, another indicator of Marvel Comics’ unique

narrative strategy. He’s played in the 2003 movie version by Ben Affleck in a

dark red rubbery suit, armed only with a multi-purpose nightstick. The film was

critically panned by both fans and professional critics, though it does serve

an important role as an example of simulated heroism mixed with identity

politics: Daredevil’s being blind makes him a champion of the handicapped.

Daredevil is thus post-ideological in a politically correct, feel good sense:

he battles the criminal mastermind the Kingpin and his flippant hitman Bullseye as a super-hero

while acting as socially concerned sight-impaired attorney Matt Murdock in his

everyday life, an attorney with so much conscience that he refuses to defend

the guilty. Added to the mix is Murdock’s devout Catholicism, which adds an air

of spiritual gravity to the character as he leaps from one cathedral spire to

another. A fourth Marvel comic book title, The Incredible Hulk, was given the

blockbuster treatment by

With

Iron Man (Jon Favreau,

2008) we get a curious mix of ideological and post-ideological narratives. Tony

Stark (Robert Downey Jr.) starts out as a dedicated member of the American

military-industrial complex who in the wake of new geopolitical realities has

found his arms-manufacturing business turned by Obadiah Stone (the company’s

second in command) into a more mercenary way of doing business, selling weapons

to whomever has the cold cash. When captured by an Islamic militia with its own

mini-imperialist goals, Stark becomes aware of the mass destruction his weapons

have caused, so he manufactures his Iron Man Mark I suit to escape from the

militia and destroy the Stark Industries weapons they’ve managed to buy on the

black market. When he returns home, he decides to turn swords into

ploughshares, moving Stark Industries away from arms production, while using

his much improved red-and-gold Iron Man Mark III suit to wreck some more mass

destruction on Stark Industries weapons in an unnamed Middle Eastern country.

Opposed not so much by the American military as by his own

right-hand man Obadiah Stone, in the finale they battle it out in powered

armour suits. At the end of the film Stark reveals his “Iron Man” identity

against the advice of his friends in the military, thus severing the story from

anything like the American monomyth. Robert Downey

displays all his roguish charm in the lead role. Yet in the end we’re not sure

where Iron Man stands: has he become a pacifist? Or is he merely revolted by

the possibility of his weapons being used to kill Americans? This highly

entertaining film manages to mix post-ideological pacificism

with the legitimacy of the “war on terror,” suspicion of the American military

and large corporations with support for the

In the case of all these comic book heroes from

Batman on, their heroism is post-ideological: they fight simulated (not symbolic)

enemies who are motivated not by ideology or money (at least in most cases),

but by a combination of pathology and power. They also evoke some of the

central elements of postmodern popular culture: recycling characters and

stories from less serious to more serious cultural forms, the emphasis on style

over substance, the breakdown of high art, and the decline of grand narratives

(except insofar as themes like the struggle against racism can add a bit of

spice to the techno-virtual stew of films like the X-Men). Comic book culture was once largely the innocent preserve

of excited young boys handing over their precious dimes and quarters to

convenience store clerks for the latest number of Batman, Spider-Man, or The X-Men. Now it

has washed over adult cultural industries as a veritable pop entertainment

tsunami, its narratives shifting from the good-versus-evil simplicities of pulp

fiction to the deeper, darker characters and stories found in the later Marvel

and Dark Horse Comics series.[11] Yet in the end these heroes don’t fight the ideological

enemies of the West, whatever their personal intricacies. They fight virtual

enemies in a post-ideological environment. History may not be over in the real

world, but in the world of Batman, Spider-Man and the X-Men, it is frantically

gasping for air.

******************

Videography - Films

Superman. Directed

by Richard Donner. Characters created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster. Written by Mario Puzo, David Newman,

Leslie Newman and Robert Benton. 1978.

Superman Returns. Directed by Bryan Singer. Story by Bryan Singer, Michael Dougherty and Dan Harris. Screenplay by Michael Dougherty and Dan Harris. 2006.

Batman. Directed by Tim Burton.

Characters created by Bob Kane. Story by Sam Hamm. Screenplay by Sam Hamm and Warren Skaaren.

1989. [Villain: The Joker]

Batman Returns. Directed by Tim Burton.

Characters created by Bob Kane. Story by Daniel Waters and

Sam Hamm. Screenplay by Daniel Waters. 1992.

[Villains: The Penguin & Catwoman]

Batman Forever. Directed

by Joel Schumacher. Characters created by Bob Kane. Story by Lee Batchler and Janet Scott Batchler.

Screenplay by Lee Batchler, Janet

Scott Batchler and Akiva Goldsman. 1995. [Villains: The Riddler

and Two Face]

Batman and Robin. Directed

by Joel Schumacher. Characters created by Bob Kane. Written by Akiva Goldsman.

1997. [Villains: Mr. Freeze and Poison Ivy]

Batman Begins. Directed by Christopher Nolan. Written by David S. Goyer and Christopher

Nolan. 2005.

The Dark Knight. Directed by Christopher Nolan. Screenplay

by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan. Story by

Christopher Nolan and Jonathan S. Goyer. 2008.

X-Men. Directed by Bryan Singer. Story by Tom DeSanto and Bryan Singer.

Screenplay by David Hayter.

2000.

X2. Directed by Bryan Singer. Story by Bryan Singer, David Hayter and

Zak Penn. Screenplay by Michael Dougherty and Daniel P. Harris. 2003.

X-Men: The Last Stand. Directed

by Brett Ratner. Written

by Simon Kinberg and Zak Penn. 2006.

Spider-Man. Directed by Sam Raimi. Original comic book by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko.

Written by David Koepp.

2002. [Villain: The Green Goblin]

Spider-Man 2. Directed

by Sam Raimi. Written

by Alfred Gough, Miles Millar, Michael Chabon and

Alvin Sargent. 2004. [Villain: Doctor Octopus]

Spider-Man 3. Directed

by Sam Raimi. Written

by Sam Raimi, Ivan Raimi

and Alvin Sargent. 2007. [Villains: Sandman

and Venom]

Daredevil. Written

and Directed by Mark Steven Johnson. 2003.

Elektra. Directed

by Rob Bowman. Original character created by Frank Miller. Written by Zak Penn, Stuart Zicherman and

Raven Metzner. 2005.

Hulk. Directed by Ang

Lee. Original comic book by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby.

Written by John Turman, Michael

France and James Schamus. 2003.

The Incredible Hulk. Directed

by Louis Leterrier. Written by Edward Norton and Zak Penn. 2008.

Fantastic Four. Directed

by Tim Story. Original comic by Stan Lee and Jack

Kirby. Written by Mark Frost and Michael France.

2005.

4: Rise of the Silver Surfer. Directed

by Tim Story. Story by John Turman

and Mark Frost. Screenplay by Don Payne and Mark

Frost. 2007.

300. Directed by Zack Snyder. Based on

graphic novel by Frank Miller and Lynn Varley.

Written by Zack Snyder, Kurt Johnstad

and Michael Gordon. 2006.

Watchmen. Directed by Zack Snyder. Based on the graphic novel by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. Written by David Hayter and Alex Tse. 2009.

Videography - Television Shows

Adventures of Superman. TV series

starring George Reeves as Superman, 1952-1957.

Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman. TV series, 1993-1997.

Smallville. TV series

on the life of young Clark

Spider-Man. Animated TV series. Written by Ralph

Bakshi. Directed by Ralph Bakshi and various others. 1966-1968.

Bibliography

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand

Faces. Princeton:

Jewett,

Robert and John

Gordon,

Ian, Mark Jancovich, and Matthew P. McAllister eds. Film and Comics.

Lang, Jeffrey S. &

Patrick Trimble, “Whatever

Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? An Examination of the American Monomyth and

the Comic Book Superhero,” Journal of

Popular Culture 22.3 (1988): 157-173.

McAllister, Matthew P.,

Ian Gordon and Mark Jancovich. “Blockbuster Meets

Superhero Comic, or Art House Meets Graphic Novel? The Contradictory Relationship between Film and Comic Art.” Journal of Popular Film and Television 34.3

(Fall 2006): 108-114.

Miller, Frank. Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. DC Comics, 1997 (10th anniversary edition).

Neil Rae and Jonathan

Gray.

“When Gen-X Met the X-Men.” In Gordon, Jancovich and McAllister eds., Film and Comics, 2007, 86-100.

Palumbo, Donald. “The Marvel

Comics Group’s Spider-Man is an Existentialist Super-Hero; or ‘Life Has No

Meaning Without My Latest Marvels!’ ”Journal of Popular Culture 17.2 (1883):

67- 87.

Richardson, Niall. “The Gospel According to Spider-Man.” Journal of Popular Culture 37.4 (2004): 694-703.

Strinati, Dominic.

An Introduction to

Theories of Popular Culture.

Wolf-Meyer, Matthew. “The World Oxymandias

Made: Utopias in the Superhero Comic, Subculture, and the Conservation of

Difference.” Journal of Popular Culture 36.3

(2003): 497-517.

Wright, Bradford. Comic

Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in

Comic

Books (most of these series have spin-offs):

Action Comics/Superman (DC Comics,

1938/1939 and on)

Detective Comics/Batman (DC Comics,

1939/1940 and on)

The Amazing Spider-Man (Marvel Comics

Group, 1963 and on)

Daredevil (Marvel Comics Group, 1964 and

on)

The Incredible Hulk (Marvel Comics

Group, 1966 and on)

The Invincible Iron Man (Marvel

Comics Group, 1968 and on)

The X-Men (Marvel Comics Group, 1963 and

on)