Hunting Elk in the Ruins: Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club as Neo-Situationist Satire of Consumer Capitalism

Hunting Elk in the Ruins: Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club as Neo-Situationist Satire of Consumer Capitalism

Hunting Elk in the Ruins: Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club as Neo-Situationist Satire of Consumer Capitalism

Hunting Elk in the Ruins: Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club as Neo-Situationist Satire of Consumer Capitalism

By Doug Mann, FIMS, UWO

1. Talking about Fight Club

Chuck Palahniuk’s 1996 novel Fight Club is at its core a neo-Situationist critical

satire of both consumer capitalism and of the excesses of gender politics. This satire

operates on an allegorical level that most academic critics have missed, being obsessed

with literal readings influenced by politically correct identity politics. In their focus on

the sheer number of male bodies and on the violence seen in both the book and the

film, they miss its more subtle critical message and the black humour that Palahnuik

obviously intended.

![]()

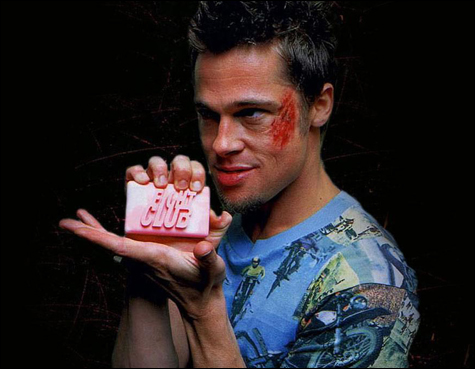

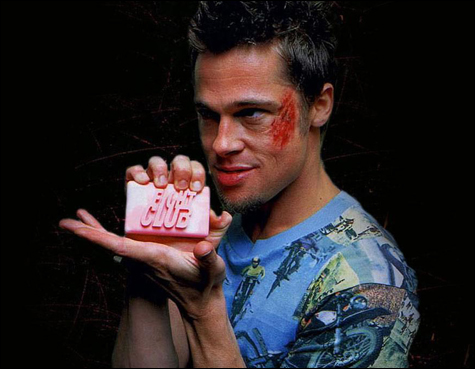

David Fincher’s 1999 film version of the book is very true to this central message, though the immediacy of the image, with its depiction of copious quantities of semi-nude male bodies (notably Brad Pitt’s), has lead critics such as Lynn Ta and Henry Giroux to read its “real message” to be an attempt by white men to reclaim their masculinity within an emasculating, feminized consumer society and thus reinforce “patriarchy.” In other words, the film is a “regressive” moment within the late capitalist gender wars.

This reading is a flawed, one-sided view that reads the film through the heavily tinted sunglasses of postmodern identity politics. When applied to the book alone, it’s at best a severe distortion of the narrative. At worst, it’s just plain false. If one reads the book after watching the film, it becomes clear that although sexual politics play a role in each, Giroux’s “crisis of masculinity” is by no means the dominant theme explored in Palahniuk’s Fight Club. Instead it’s best seen as a neo-Situationist satire about the pitfalls of consumerism and about how our economic system pacifies and alienates its citizens.

Our hero in the book is an unnamed narrator who I shall call Jack, following the critical tradition surrounding the film. Jack is, as Giroux rightly observes, “an emasculated, repressed corporate drone whose life is simply an extension of a reified and commodified culture” (263). Jack works for a recall investigator for an insurance company, travelling around the US to apply the infamous formula that balances the costs of retrofitting a defective product on the one hand against the legal costs a company would have to pay out to victims of the defective product on the other.

He lives in a condo full of Ikea furniture, fashionable knick knacks and a wide collection of condiments in his fridge. His home is a “filing cabinet” for the professional class where he can act out his slavery to his nesting instinct. He meets single-serving friends on his flights around America over single-servings of airline food. He relates to others (insofar as he relates at all) through the things he owns.

Jack’s alienation from his work and his body and his life is symbolized by his need to visit self-help groups for people with deadly diseases such as cancer and brain parasites. After visiting these groups Jack says that he’s never felt more alive, presumably because the spectre of the decaying bodies in these groups contrasts so sharply with his own healthy body, however alienated from it he might feel. The sad-sack Chloe, who is dying from brain parasites and is distraught because no one will have sex with her, tells Jack that during the French Revolution that the duchesses and baronesses in the Bastille “would screw any man who’d climb on top” (20). In other words, when faced with death we all - men and women alike - return to the very bodies from which the society of the spectacle tries to divorce us.

Tyler Durden is Jack’s alter ego in the both the book and the film, a manifestation of Jack’s freer self. As Jack himself admits, Tyler is brave, smart, funny, charming, forceful and independent. He’s capable and free, unlike “Ikea boy” Jack (Palahniuk 174). As part of his attempt to detach Jack from his precious collections of name-brand commodities, Tyler blows Jack’s condo up, which leads to their “meeting” and the formation of fight club. We get hints throughout the book that Jack, who thinks he has extreme insomnia, in fact has Dissociative Identity Disorder, and that Tyler is in fact his alternate “nighttime” self. Whenever someone else enters a room, Tyler disappears; when members of fight club see him, they obviously recognize him as Tyler; Jack himself talks about being Tyler’s mouth and his hands. By mid-novel Jack’s dual identity is a mystery only to him.

Tyler is the man that Jack wish he could be, though he seems to change his mind at the end when Tyler cooks up Project Mayhem and the mass destruction begins. Tyler isn’t afraid of taking control of his life and of attacking the corporate system. He’s a guerilla terrorist. He doesn’t care about accumulating consumer goods; he enjoys fighting for fighting’s sake; and has sex with the gothic street urchin Marla in an animalistic way, as we know from the loud noises that Jack hears from upstairs as he sits and drinks his coffee in the kitchen.

Tyler’s character is less a throwback to the fascism of the 1930s and 1940s as he

is to the anarchism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which was

every bit as violent as the fight clubs in the book. He’s also a throwback to the violent

anti-civilizational rhetoric heard in F. T. Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto, which was penned

in the same intellectual atmosphere as fin de siècle anarchism, Dada and the wider

modernist movement of the new century. We have to take him at his word that the

purpose of Project Mayhem (a subsidiary of fight club) is to break up civilization to allow

the planet’s ecology to heal, to hunt elk in the ruins of New York’s skyscrapers

(Palahniuk 124-125).

![]() It’s no surprise that these early-century movements were the

inspirations for two key anti-consumerist movements closer to our own day,

Situationism and culture jamming. These are key to understanding the satirical politics

of the novel and to a lesser degree the film.

It’s no surprise that these early-century movements were the

inspirations for two key anti-consumerist movements closer to our own day,

Situationism and culture jamming. These are key to understanding the satirical politics

of the novel and to a lesser degree the film.

2. Situationism

The obvious theoretical influence on Fight Club is the situationism of Guy Debord and the Situationist International, a group of radical theorists and artists who published the journal International Situationniste and engaged in various radical artistic and political activities in France between the late 1950s and the early 1970s. Their heyday was 1965-1968, when they had a strong influence on the student movement in France, leading up to the anti-Gaullist revolt in 1968. The Situationists heavily influenced both the British punk rock of the 1970s and the culture jamming movement that arose in North America in the 1990s.

The Situationists believed that consumer society has created a society of the spectacle where everything has become a commodity, a fetish (as Marx said all things become under capitalism). We become spectators of our own lives insofar as we immerse ourselves in consumerism, with its TV, film, radio and advertising spectacles. They felt that modern society was one that emphasized not only conformity to corporate and media control, but boredom and banalisation too. Our leisure hours are filled with preprogrammed shows. People are trained to become alienated from and bored with past acts of consumption, pushing them to consume more. More deeply, we’re trained to equate fun with consumption, and feel bored when not being fed some consumer spectacle.

The result is wasted human potential. Their solution was to take back the show, to make your own show. One of their early manifestos said that cities could be places where “everyone will live in their own cathedral” instead of the prefab architecture and lives we now inhabit. The Situationists outlined several techniques with whcih to build these cathedrals:

The Situation: This is their key concept. They wanted to breakthrough the boredom and alienation of modern life by emphasizing the situation, the event that breaks through consumerist conformity and our addiction to spectacles. In order to overcome boredom and alienation, the Situationists thought that they had to construct “situations”, to change everyday life, which is potentially made up endless moments of love, hate, delight, humiliation and surrender.

Détournement: This means to divert or turn aside. The Situationists used it in the sense of turning aside a cultural object or idea into a path other than that which it was intended to follow, to turn the system against itself. This was the sort of thing Duchamp did when he painted a moustached on the Mona Lisa and when the punks cut and pasted text and pictures into zines. The Situationists used détournement in films, posters, graphics and comics, e.g. Debord bound his book Mémoires in sandpaper to destroy other library books.

The Dérive and Psychogeography: The former term means to drift. The Situationists wanted a “unitary urbanism”, where cities could be treated as places where people could drift about in play, imbibing the psychological atmospheres of the different quarters of a city as “psychogeographers,” seeking to fulfill their desires. This was tied to the Situationists’ disdain for work. One of the slogans they painted on the walls of Paris during the May 1968 rebellion was “ne travaillez jamais,” never work.

In his book The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord says that all of life has

become a spectacle (1).

![]() We get a continuous stream of images from our culture that

prevent us from living our lives as free and autonomous beings (2). The society of the

spectacle isn’t just a society where images are everywhere, but where our social

relations are dominated by images (4). When we talk and act, we think in terms of

spectacular images, not creative or authentic pictures we make ourselves.

We get a continuous stream of images from our culture that

prevent us from living our lives as free and autonomous beings (2). The society of the

spectacle isn’t just a society where images are everywhere, but where our social

relations are dominated by images (4). When we talk and act, we think in terms of

spectacular images, not creative or authentic pictures we make ourselves.

The spectacle is the affirmation of a life lived in mere appearances, so in this sense it’s a negation of life (10). He says dramatically that the spectacle is the sun that never sets on the modern empire of passivity (13). If you think he’s exaggerating, imagine your current life, and subtract all TV, all video, all films, all mass-produced music, the Internet, shopping malls, and so on: what would be left?

Our society discourages direct personal communication (26). Technology isolates us - TV and cars help to perfect our separation, turning us into (to use David Reisman’s term) “lonely crowds” (26). The key to the process is alienation - Debord sees the consumer losing him or herself in images of need projected by the mass media, in the process losing an authentic sense of their own self (30). As new products appear, consumers are filled with religious fervour to own them. Waves of enthusiasm for new products are spread with lightning speed by the media. He even thinks that our fetishistic feelings for commodities reaches the levels of exaltation found in the ecstasies surrounding religious miracles (67).

Debord feels that the pseudo-needs propagated by consumerism have squashed our genuine needs and desires (68). Social needs are now artificially defined. This building up of the power of artificiality falsifies our social life. In other words, most of social life is phoney, created by the spectacle, not individual human beings.

3. Culture Jamming

In the 1990s a movement arose in North America which is the spiritual descendent of Situationism. This is culture jamming. Its bibles are Kalle Lasn’s magazine Adbusters and his book Culture Jam. Culture jammers are media activists who want to change the world by changing the way we interact with media and the marketplace. In his Introduction Lasn lays down six theses that help structure the arguments in his book which are also clearly relevant to Tyler Durden’s crusade in Fight Club (12-14):

(1) America is no longer a country, but a multi-trillion dollar brand. This is true both of the obvious brands such as McDonald’s, Marlboro, GM and Nike, but also of political concepts such as “democracy” and “freedom,” not to mention youthful rebellion. Political leaders bow to corporate power, yet say that America is the most democratic and freest country in the world. This is an illusion.

(2) American culture is no longer created by the people. As the Situationists said, we buy our entertainments and regard them like spectacles, whether it’s brand-name clothes, celebrities, TV, film, or the Internet. We listen, watch, then buy - but make almost nothing ourselves.

(3) A free, authentic life is no longer possible in America. Our emotions and values have been manipulated by the media. We have been branded, leading designer lives - sleeping, eating, driving, working, shopping, watching TV, sleeping again. Our free, spontaneous minutes have been swallowed up by the inauthentic images of cool and happy people dispensed by the media. Yet underneath all those happy faces lies a horror show of alienation and isolation.

(4) Our mass media dispense a kind of Huxleyan “soma”. The media hand out the narcotic of belonging, of being cool. This soma is highly addictive - you just can’t get enough of it. As many cultural critics have noted, cool is the grand seduction of modern consumerism.

(5) American cool is a global pandemic. Local communities, cultures, traditions and histories are being wiped out by a barren American monoculture - Japanese kids buy Calvin Klein, eat at McDonald’s, dream about becoming baseball players.

(6) The Earth can no longer support the lifestyle of the cool-hunting American-style consumer. This orgy of consumption has lead to a depletion of the planet’s resources, pollution, global warming, and species extinctions. The possibility of ecocide, or the death of the planet, is becoming a possibility.

Lasn suggests that culture jamming is a solution to the above problems. First, he suggests subtervising: making ads which look like real ones but which make fun of advertising (we see this in the film of Fight Club when some space monkeys change a billboard). He also suggests TV jamming (with anti-commercials), cyberjamming (using phoney web sites, overwhelming corporate sites with emails, etc.) and events like Buy Nothing Day. Lasn wants to “uncool” specific segments of the consumer market - the fast food industry (e.g. McDonald’s), the fashion industry (Calvin Klein), and the automobile industry. He thinks that activists should demarket these industries to live happier lives and help keep the environment healthy.

Overall, the culture jammer tries to jam up consumer culture with anti-ads, the Internet, public events, acts of vandalism against corporate images, and by buying nothing. Lasn makes clear that culture jamming’s theoretical parent is Situationism, with its critique of the commodity fetishism and alienation of consumer society and how these make everyday life boring and banal.

4. Masculinity Feminized

4. Masculinity Feminized

A secondary theme in Fight Club, one which is much clearer in Fincher’s film than

in the book, is how modern men have been feminized by popular culture, the self-help

movement and, most importantly, consumerism. Though this is clearly an element in

Palahniuk’s book, politically correct critics obsessed with identity politics have elevated

this into the sole motif of the story worthy of commentary.

![]() As Kevin Alexander Boon

hints, these critics are caught up in a turn-of-the-century anti-aggression rhetoric that

traps American men in a Catch 22: they’re expected to defend home, family and nation

aggressively, yet shamed into eschewing aggression in the public realm by a guilty

association of all historical violence with the Y chromosome. Hence Jack’s split identity:

one-half repressed New Age consumer, the other half primal warrior.

As Kevin Alexander Boon

hints, these critics are caught up in a turn-of-the-century anti-aggression rhetoric that

traps American men in a Catch 22: they’re expected to defend home, family and nation

aggressively, yet shamed into eschewing aggression in the public realm by a guilty

association of all historical violence with the Y chromosome. Hence Jack’s split identity:

one-half repressed New Age consumer, the other half primal warrior.

Fincher and Pahlaniuk seem to be saying that modern consumer culture is one of Nietzsche’s slave moralities which seeks to celebrate domesticity and weakness by offering modern men the comfortable lifestyle of Jack’s (Ed Norton in the film) condo filled with Ikea furniture, fancy dishes and other yuppie knick knacks. Yet this only serves to chain them to their corporate jobs and the massive doses of external control and repression that comes with them.

There are many hints in both the book and the film about how society has become feminized by consumerism and political correctness. The most obvious metaphor for this is seen in the testicular cancer support group, where Jack first meets Bob. Due to his cancer he’s had his balls removed, and the excess of estrogen in his system has given him huge “bitch tits”. The former body builder has become a surrogate woman.

Soon after Jack and Tyler create fight club, Jack muses that he belongs to a generation raised by women, and that he’s a 30-year-old boy who’s wondering if another woman is what he really needs (50-51). Earlier, in the bar, Tyler consoles Jack over his condo being blown up by telling him it could be worse: a woman could cut off his penis and throw it out the window, echoing the fate of John Wayne Bobbitt.

Tyler also makes explicit the story’s critique of self-help groups that Jack and Marla get caught up in. He says that “maybe self-improvement isn’t the answer... Maybe self-destruction is the answer” (49). It’s not accidental that the self-help groups which Jack attends are full of emotional basket cases on their path to death. They symbolize the worst case scenarios of our consumer culture as a whole. The whole idea of self-improvement is tied to consumerism in general in that both seek to attach emotional parasites to the body of their human hosts, the former draining self-confidence, the latter contentment.

Fight Club, if taken literally, is a pseudo-solution to feminization and the temptations of self-improvement. It’s aggressive and violent for its own sake, yet pales in comparison to the level of violence seen in many action films, TV and video games. It’s an attempt to re-masculinize men, to return them to a fragment of their hunter/ warrior heritages, at least on the allegorical level. But on a deeper level, the point of Tyler’s over-the-top culture jamming is to “teach each man in the project that he had the power to control history” (122). Whether or not Palahniuk uses “man” in the masculine or generic sense here is unclear, though there’s enough ambiguity to suggest that his message is at least in part a universal one.

5. Fight Club as a Critique of Consumer Capitalism

Fight Club is at its core a satirical critique of consumer capitalism.

Tyler is a situationist and culture jammer. He believes in creating situations in everyday life to live that life more freely, to challenge the society of the spectacle at its core. He doesn’t buy consumer products (in fact, he makes some himself - niche market soap), lives in a run down mansion, doesn’t have a regular job, and organizes a bunch of other culture jammers to perpetrate acts of mischief and mayhem against consumer capitalism. He himself jams consumer culture in a number of ways: he splices single frames of porn into family movies, pisses in the soup served to rich people in the Hotel Pressman’s restaurant, and makes expensive soap out of fat sucked out of rich women at a liposuction clinic.

Later his

protégés, the more violent Project Mayhem, sets fires in a corporate

building and paints a demon face on its side, threaten to cut off the balls of officials

who try to shut fight club down, and play deadly games of chicken on the freeway. Yet

this more open violence is in keeping with Palahniuk’s desire to satirize not only

consumerism, but also its more extreme opponents. When Tyler assassinates a hostile

local official we have to ask ourselves why we would take this as “real” violence while

seeing the violence in a Rambo or Die Hard film as mere fantasy.

![]()

Of course, the key anti-consumerist allegory in the book is the creation of fight club itself. It goes without saying that in the real world the activities of a “fight club” would be both very bad for its participants’ collective health and not a very good model for solving social problems. Yet part of Palahniuk’s rationale for the creation of the fight club, as he says in his Afterword, is to compete with the espresso machine and ESPN in the café where he first read his work (216). On a deeper level, he’s trying to compete with the orgy of violence seen in American popular culture, which is usually expressed in the mass slaughter allowed by the modern technology of war (witness the Terminator films or Black Hawk Down).

Fist fighting is positively archaic compared to the carnage one can create with a modern Gatling gun fired from a helicopter hovering over a Vietnamese or Iraqi village. The fact that we see it as more shocking than the push-button killing typical of the Gulf Wars of 1991 and 2003 speaks to Palahniuk’s attempt to use the upfront violence of the fight club to make an allegorical point about how the infantile ethos of modern consumerism alienates us from our bodies as the primal sites for Eros and Thanatos.

Tyler is very explicit in his Situationist, anti-consumer philosophy. In a speech to

the fight club itself, Tyler situates his philosophy in historical terms:

Tyler is very explicit in his Situationist, anti-consumer philosophy. In a speech to

the fight club itself, Tyler situates his philosophy in historical terms:

“I see the strongest and smartest men who have ever lived... and these men are pumping gas and waiting tables. You have a class of strong men and women, and they want to give their lives to something. Advertising has these people chasing cars and clothes they don’t need. Generations have been working in jobs they hate, just so they can buy what they don’t really need. We don’t have a great war in our generation, or a great depression, but we have a great war of the spirit. We have a great revolution against the culture. The great depression is our lives. We have a spiritual depression.” (149)

Tyler’s speech is not that far from the Frankfurt’s School’s critique of consumerism,

especially Herbert Marcuse’s notion that capitalism today feasts on the false needs

created by mass media.

![]() The above speech is repeated with some changes in the film,

though Fincher and screenwriter Jim Uhls have edited out some of the explicit Marxist

rhetoric found in Palahniuk’s book, e.g. when Tyler concludes the above rant with the

following comments that are worthy of a Rosa Luxemburg or the radical Winnipegers of

1919:

The above speech is repeated with some changes in the film,

though Fincher and screenwriter Jim Uhls have edited out some of the explicit Marxist

rhetoric found in Palahniuk’s book, e.g. when Tyler concludes the above rant with the

following comments that are worthy of a Rosa Luxemburg or the radical Winnipegers of

1919:

“Imagine, when we call a strike and everyone refuses to work until we redistribute the wealth of the world.”

Earlier Tyler tells Jack that working at the Pressman Hotel as a waiter will “stoke your class hatred” (65). When the hotel manager discovers his shenanigans with the hotel’s food, Tyler (somewhat tongue in cheek) tells him that he’s part of a protest against the exploitation of workers in the service industry (115). Jack refers to Tyler in several instances as a “minimum-wage despoiler,” as a service-industry terrorist, or as a guerilla waiter. Although some of this Marxist language is no doubt intended to be satirical, there’s just enough of it in the book to believe that Tyler takes the class struggle seriously.

His anger and revolt against consumerism is the ground of Tyler’s culture

jamming attitude. The idea that we over-identify with the products we consume goes

back to Marx’s idea of commodity fetishism, which also arises in the work of the

Frankfurt School and in Guy Debord’s critique of the society of the spectacle. After

blowing up Jack’s condo in the film, he tells Jack that the “things you own end up

owning you.” Tyler echoes the Situationist view of the dangers of commodity fetishism

in a second key speech, when he tells his fight club colleagues that “you’re not how

much money you’ve got in the bank. You’re not your job. You’re not your family, and

you’re not who you tell yourself.”

![]() (Palahniuk 143).

(Palahniuk 143).

This points to the existentialist side of Situationism, the idea that we are what we have done, not the sum total of things we have accumulated nor the economic roles we’re stuck in. In a key scene, Jack accosts Raymond Hessell, a sales clerk at a variety store. Tyler holds a gun to his head and asks him what he really wanted to be. He tells him he wanted to be a veterinarian, so Jack tells him he’ll kill him if he doesn’t go back to school. In other words, don’t live in bad faith like the coward Garcin in Sartre’s No Exit, but take responsibility for your choices and be what you want to be.

The empty promise of consumerism that everyone can be healthy, happy and successful if only they try hard enough, a thin disguise for the continuation of old class structures, is brought to light by Tyler with Debordian intensity when he warns the local police commissioner that people he’s trying to repress are everyone he depends on to do his laundry, to cook and serve his dinner, to drive ambulances and taxis, to process his insurance claims and credit cards. In other words, the class of service industry workers control every part of his life. He warns the commissioner:

“We are the middle children of history, raised by television to believe that someday we’ll be millionaires and movie stars and rock stars, but we won’t. And we’re just learning this fact,” Tyler said. “So don’t fuck with us.” (166)

In other words, these “middle children” were raised in a culture of the image that bombarded them with pictures of fame and wealth most would never achieve. When they realize this gap between promise and fulfilment, they became angry, hence the fight clubs.

There is even a postmodern side of Jack and Tyler’s picture of the society of the spectacle. Jack describes how insomnia washes everything out, making things seem like a copy of a copy of a copy. His insomnia distances Jack from this daytime activities, notably his job. Fincher illustrates this in the film in a scene where an exhausted Jack is using the photocopier: he gives us a brief closeup of a Starbucks logo on a coffee cup, the corporate brand being the perfect example of a simulation of nothing, “a copy of a copy of a copy.” Further, Tyler himself isn’t real, but a simulation of Jack’s hidden desire for freedom from his old life. Tyler and Jack’s world is one not only of consumer spectacles, but also of postmodern simulations of the real.

In keeping with culture jamming precepts, Tyler also mixes in a bit of Buddhist non-attachment with his critique of consumerism. He tells Jack (or Jack tells himself, depending on how you look at it) that “only after you’ve lost everything” are you “free to do anything” (70). Later he tells Jack that he’s breaking his attachment to “physical power and possessions” and that the “liberator who destroys my property... is fighting to save my spirit. The teacher who clears all possessions from my path will set me free” (110). In an ultimate evocation of non-attachment, at the end of the book Tyler tells Jack that all his loved ones will reject him or die, and that everything he creates will one day be thrown away as trash (201). In these and other pronouncements Tyler combines the Eastern philosophical disjunction between things and enlightenment with the Marxist critique of commodity fetishism.

The dark side of the story comes when Tyler begins to recruit “space monkeys” for Project Mayhem, his loyal followers, who dress in black and blindly follow Tyler’s orders. This is the mildly fascist side of the story, though to be fair Jack seems to be shocked at their activities and to reject the violence that leads to Bob’s death. When they chant “his name is Robert Paulsen” over and over, things are becoming too cult-like. However, these events once again have a satirical edge, especially given the absurdity of some of Project Mayhem’s activities.

The differences between the endings of the book and the film are interesting. In the former, Jack seems to unconsciously project into Tyler a botched recipe for explosives - nitro and paraffin - which fails to explode at the right moment, saving the Parker-Morris Building (and thus Jack himself) from destruction. Yet in the film we see Project Mayhem actually blow up a series of credit-card buildings to destroy the credit system underlying consumer capitalism in a scene which could be described as an orgy of destruction. Keep in mind the film appeared two years before 9/11, and would probably have been impossible after it.

In both the book and the film, Jack shoots himself, thereby shocking Tyler out of his system, in effect “killing” him, and mends fences with Marla, in the film holding her hand as they watch the collapse of the consumer credit system. Yet there’s no reason to assume that Jack will give up on Tyler’s project of breaking up civilization to make something better out of the world (208). His anarchist dream is still alive in both the film and the book:

"You’ll hunt elk through the deep canyon forests around the ruins of the Rockefeller Center, and dig clams next to the skeleton of the Space Needle leaning at a forty-five-degree angle. We’ll pain the skyscrapers with huge totem faces and goblin tikis, and every evening what’s left of mankind will retreat to empty zoos and lock itself in cages as protection against bears and big cats and wolves that pace and watch us from outside the cage bars at night." (124)

Hunting elk in the ruins is neither a fascist nor a specifically masculine project, but an allegory for the feeling that modern industrial civilization, and the consumerism it gave birth to, may not have been worth it in terms of the economics of happiness. It’s the same feeling that Freud had in Civilization and its Discontents, will no doubt be felt by future Tyler Durdens who contemplate the increasingly complex edifices of their own modernities. We trade away some of our primal instincts for civilized life, yet the ghosts of those instincts never entirely leave the human machine. Hence Fight Club.

Bibliography

Bainbridge, Caroline and Candida Yates. “Cinematic Symptoms of Masculinity in

Transition: Memory, History and Mythology in Contemporary Film.” Psychoanalysis,

Culture and Society 10 (2005): 299-318.

Boon, Keith Alexander. “Men and Nostalgia for Violence: Culture and Culpability in Chuck Palahniuk’s Figth Club.” Journal of Men’s Studies 11.3 (2003).

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. Black & Red. 1967. Translation from 1977.

http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/pub_contents/4

Giroux, Henry A. “Brutalized Bodies and Emasculated Politics: Fight Club, Consumerism and

Masculine Violence.” Breaking in to the Movies: Film and the Culture of Politics, Oxford: Blackwell,

2002, pp. 258-288.

Lasn, Kalle. Culture Jam: The Uncooling of America. New York: Eagle Brook, 1999.

Mann, Douglas. Understanding Society: A Survey of Modern Social Theory. Toronto: Oxford

University Press, 2008.

Marcuse, Herbert. One-Dimensional Man. Boston: Beacon Press, 1964.

Palahnuik, Chuck. Fight Club. New York: Norton, 2005 (first published in 1996).

Ta, Lynn M. “Hurt So Good: Fight Club, Masculine Violence, and the Crisis of Capitalism.” The Journal of American Culture 29 (2006): 265-277.

Fight Club. Directed by David Fincher. Written by Jim Uhls. 1999.