2. Comics into Film

2. Comics into FilmPlay Lara Play, Run Lola Run: Reflections on Postmodern Comic Book and Video Game Culture

by Douglas Mann

In the great realms of social and cultural theory, "postmodernism" is surely one of the most powerful buzzwords of the last generation. Postmodern theory has shown itself to have as many heads as the mythical Hydra. Just as one of these heads is cut off by the sober analysis of philosophers of language or the outraged slings and arrows of disgruntled cultural conservatives, it sprouts another.

Yet, as Dominic Strinati points out, just what cultural phenomena count as "postmodern" and which ones don't is not always made too clear in the ongoing debate about the value of postmodernism.(1) That's what I'll attempt to do here with this major movement in popular culture. The use of comic-book and computer-game characters as heroes and heroines of mainstream Hollywood movies, along with the creation of whole movies with computer software, represents a trend toward virtual reality that fits into a number of the elements of postmodern culture. Notably, they reflect the following postmodern trends:

This essay will be divided into three parts. First we will look at the way that major comic book characters have been recycled as action heros in major Hollywood films. Secondly, we'll turn up the virtual heat a few degrees by looking at how computer games have morphed into multi-faceted cultural phenomena, amongst other things being turned into semi-serious cinematic narratives. Finally, we'll show how comic book and video game culture is celebrated in the German film Run Lola Run, an important landmark in the coming of age of postmodern popular culture. So up, up and away!

2. Comics into Film

2. Comics into Film

A. The DC Superheros: Superman and Batman

The most famous superhero is probably DC Comics' Superman, who made his first appearance in Action Comics in 1938, getting his own book a year later. The Man of Steel, a refugee of the planet Krypton, is almost invincible: he can only be defeated by the element kryptonite, a fragment of his home world. He can fly, lift huge weights, deflect bullets from his chest, and jump tall buildings with a single bound.

Superman crossed over from the comic book page to film and television soon after his first appearance in 1938 in Action Comics, and has had an almost continuous existence outside these pages. George Reeves starred as Superman in Adventures of Superman, a TV series based on the comic-book character broadcast from 1952-1957. Several other series concerning Superman have aired, including Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman (1993-1997), which made Teri Hatcher a minor celebrity for playing the role of Lois Lane, and Smallville, on the air since 2001, about the young Clark Kent. The characters on this show take themselves rather seriously - it's part superhero story, part teen drama. There have also been a number of cartoon versions going back to the package of seventeen shorts created by Max and Dave Fleischer in 1941. The definitive movie versions of the Superman story are the four films starring Christopher Reeve as the Man of Steel. They appeared in 1978, 1980, 1983, 1987, and were as big an element of 80s pop culture as were the Batman movies in the 90s.

Superman is comparatively stiff compared to most of the other superheros, a do-gooder without emotional depth. He doesn't have the personal problems of the Marvel superheros, other than protecting his secret identity from nosey reporters. In a lot of ways he's more like the heroes of 1930s serials than later comic book characters - he's not a model for real people and doesn't care about social problems.(2) In fact, he's not even human, but a refugee from the planet Krypton. He harkens back to an earlier age of science fiction and comic books, when the heroes were lily white, and the villains dark and nefarious. The films certainly illustrate the way that Hollywood has recycled other pop cultural forms into a cinematic form. Yet the Man of Steel is no fan of a Lyotardian decline of meta-narratives, preferring instead Truth, Justice and the American Way.

Batman also goes back to the innocence of the pre-WWII period in American comics, making his first appearance in Detective

Comics in 1939, and in his own book in 1940. His adventures were turned into a set of serial shorts in 1943 (Superman had to

wait until 1948 for a serial adaptation). Batman became part of kitschy pop culture in the 1960s with the tongue-in-cheek TV

version of the comic book starring Adam West as the main character. Batman dresses in a bat costume made of tights and

boots, rides around in his batmobile, and uses his brains and all sorts of neat gadgets to defeat enemies like the Penguin, the

Riddler, and Catwoman. In the TV series he is shown with his partner Robin (Burt Ward) the Boy Wonder in place right from

the start. The fights are corny, adorned with cartoon bubbles with "zowee" and "kaboom". The best written episodes,

especially those by Lorenzo Semple Jr., are full of sly humour and visual puns. This incarnation of Batman never took itself

too seriously - in its own way it was part of the pop art movement lead by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein.

Batman also goes back to the innocence of the pre-WWII period in American comics, making his first appearance in Detective

Comics in 1939, and in his own book in 1940. His adventures were turned into a set of serial shorts in 1943 (Superman had to

wait until 1948 for a serial adaptation). Batman became part of kitschy pop culture in the 1960s with the tongue-in-cheek TV

version of the comic book starring Adam West as the main character. Batman dresses in a bat costume made of tights and

boots, rides around in his batmobile, and uses his brains and all sorts of neat gadgets to defeat enemies like the Penguin, the

Riddler, and Catwoman. In the TV series he is shown with his partner Robin (Burt Ward) the Boy Wonder in place right from

the start. The fights are corny, adorned with cartoon bubbles with "zowee" and "kaboom". The best written episodes,

especially those by Lorenzo Semple Jr., are full of sly humour and visual puns. This incarnation of Batman never took itself

too seriously - in its own way it was part of the pop art movement lead by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein.

The polar opposite of the campy 1960s TV series was Tim Burton's evocation of the later, much grittier version of Batman based on the "Dark Knight Returns" series of DC comics drawn by Frank Miller, the graphic novel compilation appearing in 1986. Burton's 1989 Batman movie starred Michael Keaton as the Dark Knight, with Robin nowhere in sight. Gotham City is portrayed as a sort of art deco monstrosity, with monumental statues and dark alleyways. His enemy is the Joker (Jack Nicholson), who killed his parents years earlier while a small-time hood. The Joker has been disfigured by a chemical spill, and has become a homicidal maniac.

The first sequel was Batman Returns (1992), with Burton still at the helm. In this film Batman battles the Penguin (Danny De Vito) and Catwoman, played as a sort of vengeful feminist heroine by Michelle Pfeiffer. Christopher Walken does his usual menacing thing as the crooked businessman Max Shreck. In both the Burton films, Batman's enemies are vicious criminals who deserve their fate. The next two sequels were less successful artistically speaking. Batman Forever (1995) sees Burton gone and Joel Schumacher as the new director, with Val Kilmer as Batman. A petulant Robin (Chris O'Donnell) becomes his partner in crime fighting. Their enemies are Tommy Lee Jones as Two-Face and a typically over-the-top Jim Carrey as the Riddler. In Batman and Robin (1997), George Clooney takes over the title role. Batman is teamed once again with Robin, while Alicia Silverstone pops up as Batgirl. The tremendous trio fight Arnold Schwartzenegger as Mr. Freeze and Uma Thurman as Poison Ivy. A return to the camp humour of the sixties' series seems just around the corner.

Obviously, the Batman franchise is a powerful example of TV and film recycling comic book culture. We can also see it as an example of the breakdown of high art and the penetration of pop culture into mass consciousness - more people know and take seriously Batman than characters from the novels of Dickens, Dostoevsky or Jane Austen. He's as famous as any poet or composer, his image and story instantly recognizable by most people under the influence of American mass culture. Yet there is a shadow of the old good-versus-evil meta-narrative in the Batman stories, even if the Dark Knight's motives for fighting crime have more to do with revenge for the death of his parents than any high-minded concern with truth and justice. This is certainly ambiguous, with one bat foot in modernism, and the other in the postmodern. To be continued.

B. The Marvel Superheros: The X-Men, Spiderman and Daredevil

B. The Marvel Superheros: The X-Men, Spiderman and Daredevil

X-Men (2000), which stars the distinguished British actors Patrick Stewart as Dr. Xavier and Ian McKellan as the villain Magneto, is the movie version of the Marvel comic book series The Uncanny X-Men, which dates back to 1963. The X-Men are mutants, human beings who have been given special powers due to genetic mutations. They share some of the characteristics of all Marvel superheros: they have ordinary lives when not being superheros, are misunderstood by the masses, and have the same personal problems as everyone else, magnified times ten due to the heavy burdens of super-herodom.

The X-Men include Cyclops, who shoots a powerful ray from his eyes (he is thus stuck wearing sunglasses when not in his crime-fighting gear), Storm, who can control the weather, and Jean Grey, who has telekinetic powers. They are lead by Dr. X, played by Patrick Stewart, who is crippled but has tremendous mental powers. A late addition to the group is the popular character Wolverine (Hugh Jackman), a Canadian who sprouts claws from his hands and has a bad attitude toward authority. The interesting thing about the film is that there are also "bad" mutants who don't trust ordinary humans. Yet this is for good reason - some politicians are seen trying to pass a law to imprison or banish all mutants. In a flashback at the start of the film we see the leader of the bad mutants Magneto as a young boy in a Nazi concentration camp, driving home the supposed central theme of the movie: the wrongness of discrimination against groups of people based on biological difference.(3) However, this theme is so old hat in Hollywood, being played out time and time again from the anti-Nazi films of the 1940s from the Warner Brothers and other American filmmakers to Spielberg's Schindler's List (1993) and Amistad (1997), that it is in danger of becoming hackneyed. Yet this old-fashioned liberal homily is played against the backdrop of a virtual world populated by refugees from pulp story-telling originally aimed at teenagers. In addition, the mutants evoke the postmodern trope of pastiche: they are half human, half something else, in some cases part animal (like Toad), in other cases part super-human.

We see impressive special effects in the film: the evil mutant Mystique (Rebecca Romijn-Stamos) changes her physical appearance several times; her boss Magneto levitates through the air and lifts police cars, guns, and other metal objects with the power of his mind; while Storm (Halle Berry) conjures up veritable tempests to brush aside her enemies. The sequel, X2, released in May 2003, replays many of the same themes as the original.

Spiderman is one of the most famous of the Marvel superheros. He is in the Marvel mould of being an ordinary guy thrust into

the role of being a hero by a freak accident - he was bitten by a radioactive spider, and gained extraordinary strength, the ability

to climb walls, and a sixth sense that is aware of danger before it happens. He develops a device that shoots sticky webs from

his hand across large distances, hence his nickname "the webslinger". His motives are suspected by J. Jonah Jameson, the

publisher of a tabloid newspaper that ironically Peter Parker, the real man behind the mask, works for as a freelance

photographer. The spectacularly drawn special editions of The Amazing Spiderman comic book drawn by Todd McFarlane in

the late 1980s and early 1990s helped to revive the character. There was also a crudely drawn cartoon TV series dating from

1967-1970 directed by Ralph Bakshi that spawned the theme song for Spiderman: "Spiderman, Spiderman, Does whatever a

spider can...," of which the Ramones recorded a delightful cover.

Spiderman is one of the most famous of the Marvel superheros. He is in the Marvel mould of being an ordinary guy thrust into

the role of being a hero by a freak accident - he was bitten by a radioactive spider, and gained extraordinary strength, the ability

to climb walls, and a sixth sense that is aware of danger before it happens. He develops a device that shoots sticky webs from

his hand across large distances, hence his nickname "the webslinger". His motives are suspected by J. Jonah Jameson, the

publisher of a tabloid newspaper that ironically Peter Parker, the real man behind the mask, works for as a freelance

photographer. The spectacularly drawn special editions of The Amazing Spiderman comic book drawn by Todd McFarlane in

the late 1980s and early 1990s helped to revive the character. There was also a crudely drawn cartoon TV series dating from

1967-1970 directed by Ralph Bakshi that spawned the theme song for Spiderman: "Spiderman, Spiderman, Does whatever a

spider can...," of which the Ramones recorded a delightful cover.

The film version from 2002 uses spectacular special effects of an all-virtual CGI Spiderman swinging from building to building as he does in the comic books, which would have been technically impossible a couple of decades ago. It's directed by Sam Raimi. His foe is the Green Goblin, played with verve by Willem Dafoe, a millionaire deranged by his own experimental nerve gas experiment. In it we are given a glance of insight into Peter Parker's teenage angst - just enough to make the film true to the spirit of the comics.

Lastly, Daredevil is a blind lawyer who fights crime mainly with his radiation-enhanced strength and extrasensory awareness that's a bit like radar, a sort of poor man's Spiderman. Certainly the vulnerability of a blind man to enemies is a far cry from Superman's near invincibility, another indicator of Marvel Comics' unique narrative strategy. He's played in the 2003 movie version by Ben Affleck in a dark red rubbery suit, armed only with a multi-purpose nightstick. The problem associated with both these films is whether the characters survive under the special effects and fight sequences, which tend to have the greatest appeal to most of the films' viewers, especially kids.(4)

Yet in all cases they evoke some of the central elements of postmodern popular culture: recycling characters and stories from less serious to more serious cultural forms, the emphasis on style over substance, the breakdown of high art, and the decline of grand narratives (except insofar as themes like the struggle against racism can add a bit of spice to the techno-virtual stew of films like the X-Men). Comic book culture was once largely the innocent preserve of excited young boys handing over their precious dimes and quarters to convenience store clerks for the latest number of Batman, Spiderman, or The X-Men. Now it has washed over adult cultural industries as a veritable pop entertainment tsunami, its narratives shifting from the good-versus-evil simplicities of pulp fiction to the deeper, darker characters and stories found in the later Marvel and Dark Horse Comics series.(5) A return to simpler hyper-realities for these excitable boys required a new technology, the home computer revolution of the last three decades.

A. Video Games: Lara Croft and Tomb Raider

From late 1970s on, home computers offered kids an alternative to the fantasy worlds presented in comic books in the form of the computer game. At first crude tests of one's reflexes (e.g. Pong and Space Invaders), by the mid-1990s games for home computers offered rich simulated environments in fantasy role-playing adventures, strategy games, and good old-fashioned arcade-like shoot-em-ups.

Tomb Raider is a series of a half dozen role-playing computer games plus a number of expansion kits going back to 1996,

created by the British company Core Design and marketed by Eidos Interactive. The heroine of the game is Lara Croft, the

athletic and educated daughter of an aristocratic English family. She explores ruins and tombs in exotic locales, discovering

relics in them that often have magical powers. In the game the player controls Lara's character, making it a role-playing

adventure game. She can run, swim, jump over obstacles, climb ropes, and blast bad guys and vicious beasts with a pair of

9mm pistols. She grunts, sighs and makes other noises when straining herself or injured, speaking occasionally to other

characters in the game.

Tomb Raider is a series of a half dozen role-playing computer games plus a number of expansion kits going back to 1996,

created by the British company Core Design and marketed by Eidos Interactive. The heroine of the game is Lara Croft, the

athletic and educated daughter of an aristocratic English family. She explores ruins and tombs in exotic locales, discovering

relics in them that often have magical powers. In the game the player controls Lara's character, making it a role-playing

adventure game. She can run, swim, jump over obstacles, climb ropes, and blast bad guys and vicious beasts with a pair of

9mm pistols. She grunts, sighs and makes other noises when straining herself or injured, speaking occasionally to other

characters in the game.

She is athletic, intelligent, active, and strong, and has the sort of body that exists only in the minds of excitable young male computer geeks who spend too much time in their bedrooms. She is an ambiguous heroine for feminists. Most of them have criticized the character as having a hyper-exaggerated body (with measurements of 34D-24-35 according to her virtual CV on the Tomb Raider website) and female sexuality designed for men's pleasure, and thus as perpetuating the beauty myth. They argue that her body proportions are grossly unnatural, setting an impossible standard of physical perfection for women. Also, they argue that Lara Croft acts as an unhealthy role model for young girls, sexualizing them at an early age with images provided by male fantasy. Birgit Pretzsch, the author of a thesis and web page on Lara, argues that her body can be critiqued on three specific levels: (a) as a Foucauldian docile body that symbolizes how images of female beauty compel women to "improve" and subjugate their bodies, (b) as an idealised "commodity woman" saturated with capitalist discourse, and (c) for reinforcing biological difference with its hypersexualization.(6) Certainly, most feminists would agree that she is a pure commodity, her body a virtual sexual object to be consumed by the game's mostly male players. She represents a disposable virtual fantasy for teenaged boys. Like most other commodities, she can be used at any time - just pop the game CD into your drive and there she is!

Yet on the other hand, she doesn't quite fit the typical roles for women in video games, that of damsels in distress waiting to be rescued by hyper-masculine male characters like Duke Nukem, or of easy sexual conquests waiting around for the hero of the game to defeat the bad guys and claim as their due reward. In fact, some women, usually not radical feminists, have suggested that despite her curvaceous proportions, Lara Croft is a positive role model for young women - after all, she's smart, independent, adventuresome, athletic, and kicks butt without the help of men. So is Lara Croft just an exaggerated male fantasy? Or is she a Third Wave feminist role model who can take care of herself? Most likely a bit of both.

Be that as it may, Lara Croft illustrates a number of elements of postmodern culture. We can see in her:

First of all, the game has been promoted by a series of actresses and models who dress up like Lara and appear at computer fairs and conventions. They try to match, though can never live up to, Lara's hyperreal body. They wear sunglasses and her trademark costume (aqua top, skimpy shorts, exaggerated gun belt), and use other props such as toy guns and a motorcycle to impress their audience.

In addition, Lara Croft has become a virtual icon on a number of web pages dedicated to her. She is featured on the official Tomb Raider page, on the Core Design and Eidos pages, and on at least another dozen fan pages that flesh out her identity with biographical details, stories, screenshots from the various games, and fan art.

Her image or persona has also been commercialized in a number of subsidiary ways: in magazine and television ads for non-Tomb Raider products, in music videos by a German punk band and by U2, in a line of comic books where she teams up with Witchblade, an alluring private detective, and in Lara Croft Magazine, a sort of virtual Playboy. These commercializations of her virtual persona are hardly surprising given the success of the game series, yet taken together probably have less impact than Lara as game character, virtual icon, or film heroine.(7)

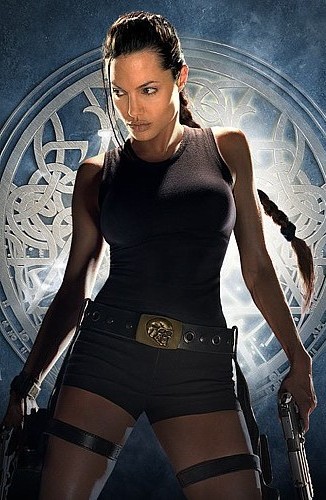

The fourth major simulation of the original game character can be seen in the film version Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001),

which stars Angelina Jolie as Lara Croft. It features a quest for a magical relic, an evil opponent, obstacles both natural and

supernatural, athletic stunts, exotic palaces and ruins, and lots of gunplay from Lara. In the film she's looking for a legendary

artifact called the Triangle of Light, which can alter time and space when the planets of the solar system align. Hot on her

heels are the Illuminati, a secret society which, in the words of the video box cover, are bent on world domination. In a key

scene in the film we see Lara arriving at the ruined temple akin to Ankor Wat in Cambodia (the real temple was used in

external shots) in search of a relic, complete with creeping vines, massive trees with sinewy roots, mouldy statues of ancient

gods, and bemused locals. The temple ruins themselves uncannily echo the backdrop of a typical Tomb Raider game,

specifically, Tomb Raider III. Jolie wears Lara's pigtails, backpack and pistols, and uses a glow stick to replace the game

character's flares. She climbs vines, explores various levels of the ruined temple, and blasts the bad guys (in this case ancient

statues which come to life) just like the virtual Lara Croft.

The fourth major simulation of the original game character can be seen in the film version Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001),

which stars Angelina Jolie as Lara Croft. It features a quest for a magical relic, an evil opponent, obstacles both natural and

supernatural, athletic stunts, exotic palaces and ruins, and lots of gunplay from Lara. In the film she's looking for a legendary

artifact called the Triangle of Light, which can alter time and space when the planets of the solar system align. Hot on her

heels are the Illuminati, a secret society which, in the words of the video box cover, are bent on world domination. In a key

scene in the film we see Lara arriving at the ruined temple akin to Ankor Wat in Cambodia (the real temple was used in

external shots) in search of a relic, complete with creeping vines, massive trees with sinewy roots, mouldy statues of ancient

gods, and bemused locals. The temple ruins themselves uncannily echo the backdrop of a typical Tomb Raider game,

specifically, Tomb Raider III. Jolie wears Lara's pigtails, backpack and pistols, and uses a glow stick to replace the game

character's flares. She climbs vines, explores various levels of the ruined temple, and blasts the bad guys (in this case ancient

statues which come to life) just like the virtual Lara Croft.

Lastly, the character and game have been simulated in the Canadian TV show Relic Hunter (1999-now), which stars Tia Carrere as a Lara Croft-style archaeologist/relic hunter. It's filmed around Toronto. In the show Carrere plays Sydney Fox, an "Ancient Studies" professor who skips most of her classes to jet to distant lands in search of relics. In each episode there is some nefarious enemy to fight, a number of obstacles or traps in the tomb or ruin being investigated, and sometimes a love interest for Sydney. She is accompanied by her teaching assistant Nigel Bailey (Christian Anholt), who provides comic relief. Contrary to feminist perceptions of gender in the video game genre, Nigel is portrayed as physically weak, having to be rescued by Sydney whenever they get into a sticky situation. Several other adventure-type television shows are now on the air where at least one of the main characters is a swashbuckling woman in search of a relic or treasure, or on some sort of quest.

So there are a multiplicity of Lara Crofts: the virtual character in the game, the models that portray her at conventions and photo shoots, the Internet icon, the commercial icon, the film character, and TV copies of the character. The Tomb Raider series is certainly the center of a copious amount of cultural recycling. Yet Lara's virtual character preceded all other portrayals of her, as Jean Baudrillard says of images in postmodern culture in general. She is what Baudrillard calls a Third Order "Simulacrum" of reality, a simulation of something that doesn't exist. He argues in his important 1984 essay "The Precession of Simulacra" that in our media-obsessed age, simulations of reality precede actual events, unlike in the past, when simulations were of already existing real things, e.g. a fake copy of a famous painting. In our Third Age of Simulacra, movies about nuclear accidents and wars precede the real accident or war, virtual characters in films and on TV are copied by real people, and computer simulations help to guide real actions in politics and war. Lara Croft is most definitely a simulacrum in Baudrillard's sense, an avatar of postmodernity. Her character has spun off from its humble video game center a spiral of simulations that show no sign of congealing into a coherent unchanging real subject anytime soon.

B. Virtual Movies: Final Fantasy

B. Virtual Movies: Final Fantasy

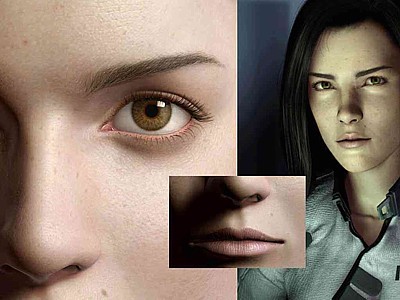

My second, briefer case study of the postmodern impulse provided by video game culture is the film Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001). It's based on a series of Japanese fantasy role-playing video games dating back to 1990.

The film has been created entirely by CGI computer software, except for the voices. It's the first effective virtual action film. In it we see a quality of simulation of human figures and machines not previously seen in films. The characters are not cartoons, but virtual actors. Not surprisingly, the film also features some fairly spectacular visual effects, as we can see in a dream sequence at the very beginning of the film that starts with a closeup of the heroine's eye followed by shots of a striking alien landscape.

The plot is a typical one for sci-fi video games: it's the year 2065, and the Earth has been invaded by wraith-like aliens. The last human beings have holed up in protective domes, original cities like New York having been reduced to wastelands where the aliens roam free. The heroine of the film is multi-ethnic Aki Ross, a combination action hero and scientist. Aki and her friends have to find a way to defeat the aliens. The troops she serves with are typical video game characters: muscular, tough, and brave. The characters' facial expressions and bodily motions are a bit stiff at times, but not cartoon-like. Voices are provided by established actors like Donald Sutherland, Steve Buscemi and Alec Baldwin. The film has a number of postmodern elements:

Some Hollywood insiders expressed concern after it came out that some day computer software would put real actors out of a job, replacing them with more manageable virtual actors. Final Fantasy puts this question front-and-center: if film makers could make films with convincing virtual actors, would people go to see them? Would they care whether or not actors, newscasters, and other media personalities were real, or just whether they "looked" real? The perfect simulation of the already simulated characters played by actors in films and television would certainly bring us fully into Baudrillard's Third Order of Simulcra, where the real is swallowed up by the hyperreal, with Max Headroom, Aki Ross and Ana Nova leading the way.

The moral of this section is that computer games have started to penetrate into the general popular culture, adding another element to the symbiotic relationship between comic books, video, film, television, and pulp fiction. Out of this pulsing ball of pop cultural energy came a slightly more serious cinematic work of art, Tom Tykwer's Run Lola Run, to which I now turn.

4. The Film as Video Game: Run Lola Run

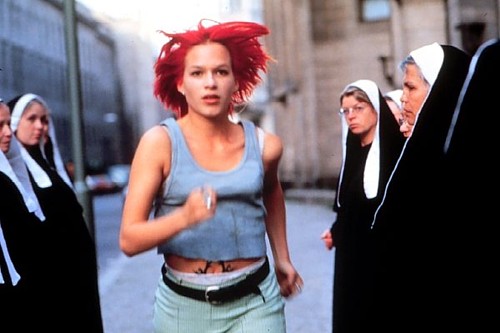

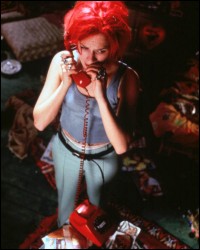

Run Lola Run, a German film from 1998 directed by Tom Tykwer, is an excellent example how comic book and video culture brings postmodern cultural elements into film. All the main elements are there:

Run Lola Run is a cinematic tour de force, with a very structured screenplay that shows that the director left nothing to chance (chance or fate is one of the main themes of the film by the way). There are no wasted shots in this 81-minute film. Its style is fast and kinetic, driven except in one short scene by a pounding techno soundtrack giving it a real energy, surging mercilessly forward toward two tentative and one final resolution. Commentators have linked its structure and style to films by Wim Wenders and Krzysztof Kieslowski, though I believe that it stands on its own two aesthetic legs, requiring no inter-textual cinematic propping up.

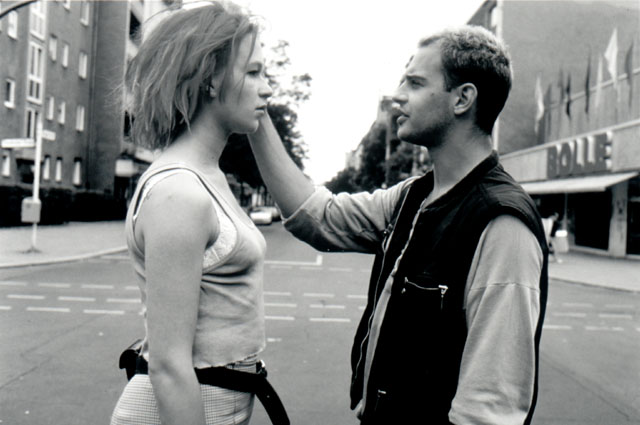

The two main characters are Lola, played by Franka Potente, and her boyfriend Manni, played by Moritz Bleibtreu. Even their real names are unintentional puns - Lola is indeed "potent" (from the Italian), while Manni tries to "stay true" to his woman.

The film is divided into three main segments divided by two red-filtered scenes of Lola and Manni in bed, fronted by a prologue that clearly defines the postmodern intentions of the film's author Tykwer. In each of the segments Lola has twenty minutes to find 100,000 marks to replace an equivalent amount of money that Manni has foolishly left sitting in a plastic bag in a subway car. He needs the money to pay off vicious gangsters he works for to avoid being "rubbed out" by them. The twenty-minute deadline is imposed by the promise Manni makes from a phone booth at the start of the film to rob a Bolle supermarket at gunpoint to get the money himself if Lola can't figure out how to raise it. In the first two segments, Lola and Manni fail catastrophically, causing one of them to die. But each time the dying character hits the reset button and plays the game again. Thus the film self-consciously echoes the structure of a video game - if Lara Croft or Aki Ross die, just hit "replay" to bring them back to life for another attempt to achieve their quest.

One obviously postmodern technique (given my definition of the elements of postmodern culture) is Tom Tykwer's mixing of

conventional colour film, short black and white segments, and video tape filmed with a hand-held camera. This is an appeal to

pastiche. The jarring contrast between the film and video tape segments highlights a shift in the emotional mood of the film:

when Lola runs in present time, she's always on colour film; but when we see her father arguing with his illicit lover Jutta

Hansen, it shifts to grainier, more subdued (at least in terms of colour) video tape. In fact, video tape is used whenever we see

just the secondary characters, and neither Lola nor Manni are on screen. The short black-and-white segments always picture

events remembered or recounted by Lola or Manni, the past pictured in the medium of the early cinema.

One obviously postmodern technique (given my definition of the elements of postmodern culture) is Tom Tykwer's mixing of

conventional colour film, short black and white segments, and video tape filmed with a hand-held camera. This is an appeal to

pastiche. The jarring contrast between the film and video tape segments highlights a shift in the emotional mood of the film:

when Lola runs in present time, she's always on colour film; but when we see her father arguing with his illicit lover Jutta

Hansen, it shifts to grainier, more subdued (at least in terms of colour) video tape. In fact, video tape is used whenever we see

just the secondary characters, and neither Lola nor Manni are on screen. The short black-and-white segments always picture

events remembered or recounted by Lola or Manni, the past pictured in the medium of the early cinema.

Tykwer plays with colour throughout the film. Red is the dominant colour, perhaps suggesting blood, death or fate. Lola's dyed hair is an extravagantly bright red; the telephone she gets Manni's plea for help at the start of the film is red; there is also a red ambulance containing a paramedic in a red coverall, a red bag full of money stolen from a grocery store, a bicycle thief wearing a red soccer shirt with "Gott" written in Gothic letters on the front, along with assorted red signs (notably the Bolle market sign), cars, and other objects. Red is the colour of decision and fate, of the gods of the film, of life and death.

In addition, black and white are constantly contrasted in the film, in the clothes of a group of nuns, in a pair of cars that crash into each other in each segment, in the dress of the employees at Lola father's bank, and even in the row of parked cars in the final scenes of each of the three games. The gangster's car at the end of the film is black, as their white car (the only one clearly seen in the film) has been smashed up in an accident. Perhaps Tykwer is playing with the old distinction between good and evil as symbolized by a chromatic dialectic between white and black. Yet it is far more likely that he is neutral on the moral content of this dialectic. The many contrasts of black and white are more likely to symbolize the clash of obstacles to Lola's progress in each of the three games, as seen most strikingly in each of the three car crashes in the film. These are always black on white - even the moped driver who piles into the back of the crashed cars in Game 3 is wearing a black helmet and a white coverall. This distinction is more like black and white in a game of chess, serving merely to distinguish adversaries.

Despite her red hair, Lola's home colours are green and white. She wears checked green pants, a sleeveless aqua shirt (just like Lara Croft), and we can see her white undergarments showing constantly. Green is the colour of nature, the body, and growth. We see lots of green trees, green vegetables in the Bolle market, green-covered walls, a clock in Lola's room with green numbers glued on it, a green garbage bag full of money Lola steals from her father's bank in Game 2, a large white tanker truck with the green letters "L" and "E" on the fender that Lola is almost run over by before entering the casino in Game 3 (perhaps her initials?), green velvet on the roulette wheel table, a pile of green and white casino chips that Lola cashes in after her victories in roulette, and a green and white ring with "GO" written on it on Lola's finger (Lola's fistful of rings makes one think of Tolkien). In the scene in Game 1 when Manni starts to rob the Bolle market and Lola arrives too late to dissuade him, Tykwer's camera frames Lola against the background of a green and white building, while Manni is framed by gold and red structures and objects behind him in the market. Lola is a force of nature and growth, with her churning green legs, whereas Manni is trapped in the worlds of a dire fate and an unhealthy need for Geld, gold, cold cash.

Gold is the fifth colour Tykwer applies liberally from his stylistic pallette. It symbolizes wealth, and perhaps blind materialism. Manni's telephone booth, from which he pleads for money from friends, is gold; the Spirale sign behind him and the door frames and checkout stalls of the Bolle market, a potential source of ill-gotten gain, are also gold; the sign over the door and many of the metal fittings in the bank are also gold. The workmen carrying a large pane of glass across the street, a precious cargo, wear gold jumpers; the rail cars Lola runs past are gold (remember: at the beginning of the film Manni left his bag of money on a subway car); the handles and main plate of the roulette wheel in Game 3 are a shimmering gold, as are the numbers on the casino betting table and the bag full of legally won money Lola carries away at the end, a treasure for her future. Tykwer's playing with colour illustrates both the film's complicated stylistic structure, but also the melding of high and popular art: we know the role of things through the way they are colour coded, just like objects and characters in a computer game.

Tykwer also emphasizes the role of time and fate in our lives. The first sound we hear other than music is the sound of a ticking clock. The opening of the film shows a gothic-looking clock ticking away its demonic second hand, another demon on its main face. The film opens when the camera plunges into the mouth of the demon on the face of the clock, warning us that the characters within it will be swallowed up by time.

We see many clocks in the film: an old clock with green numbers stuck on it in Lola's house at the start of the movie (probably

a postmodern clock!), a streamlined modern clock with a minimum of ornamentation in her father's office that Lola shatters

with her trademark scream, a tiny watch with Roman numerals on an old lady Lola asks for the time as she passes her in the

street, while a huge clock, again with Roman numerals, in the casino in the third segment announces that Lola is quickly

running out of time once again. But the mother of all clocks is the nondescript one without numbers on the wall of the Bolle

market across the street from Manni - this is the game clock, the official timepiece. It counts down the twenty minutes in each

round, just as a digital clock counts time in computer games, determining either the player's success or failure, or their score in

the game. This clock is black and white with a fateful-looking red second hand.

We see many clocks in the film: an old clock with green numbers stuck on it in Lola's house at the start of the movie (probably

a postmodern clock!), a streamlined modern clock with a minimum of ornamentation in her father's office that Lola shatters

with her trademark scream, a tiny watch with Roman numerals on an old lady Lola asks for the time as she passes her in the

street, while a huge clock, again with Roman numerals, in the casino in the third segment announces that Lola is quickly

running out of time once again. But the mother of all clocks is the nondescript one without numbers on the wall of the Bolle

market across the street from Manni - this is the game clock, the official timepiece. It counts down the twenty minutes in each

round, just as a digital clock counts time in computer games, determining either the player's success or failure, or their score in

the game. This clock is black and white with a fateful-looking red second hand.

Not only is time always ticking for Lola, just as it is for any hero of a role-playing video game, but her actions at one time affect the future fate of those she interacts with, not to mention her success at later stages of the same game. So it's very much a movie about causality, a point driven home at the start of the first segment when we see on Lola's mother's television a long row of dominoes striking each other, causing a seemingly endless series of tumbles.

On a deeper level, the movie is about karma. As Lola runs into each of her human obstacles, she changes their future, usually

without having any such intention. Even her own decisions are crucial. In the first interlude Lola tells Manni that she must

make a decision about the future of their relationship, echoing the general power of our decisions not only to change our lives,

but those of others too. In each replay of Lola's run, she encounters a standard series of obstacles, but handles them in different

ways. There are an even dozen major obstacles along Lola's path: after leaving her boozy astrology-fixated mother sitting in

their living room, Lola encounters (1) a snarling dog and a smart-assed kid on the stairway outside their apartment, (2) then a

hot-tempered, down-and-out mother named Doris pushing a baby carriage, (3) a black car driven by her father's associate Herr

Meyer, (4) a crowd of nuns, (5) Mike the bicycle thief, (6) the bum who took Manni's bag, (7) the bank guard Schuster, (8)

Lola's father and his secret lover Jutta, (9) Frau Jäger, a dark-haired woman at the bank, (10) an old woman outside the bank

of whom Lola asks the time, (11) a red ambulance speeding away with its siren blaring, and finally (12) workmen crossing

the street with a large pane of glass, just before meeting Manni at the fateful intersection. As she encounters each of these

human obstacles/potential helpers in each game her actions affect them in some way, and vice versa. Tykwer makes clear the

effect that Lola has on the lives of three of these characters with a fast series of snapshots, accompanied by the sound of a

camera shutter clicking, into that character's possible future following their encounter. Doris, Mike and Frau Jäger are given

this treatment, an odd choice given the very limited verbal interaction Lola has with them. But perhaps not so odd at all:

Tykwer may be suggesting that karmic forces are always at work. Almost trivial interventions into the lives of others can have

monumental consequences. I'll return to these "possible futures" in my synopsis of the film.

On a deeper level, the movie is about karma. As Lola runs into each of her human obstacles, she changes their future, usually

without having any such intention. Even her own decisions are crucial. In the first interlude Lola tells Manni that she must

make a decision about the future of their relationship, echoing the general power of our decisions not only to change our lives,

but those of others too. In each replay of Lola's run, she encounters a standard series of obstacles, but handles them in different

ways. There are an even dozen major obstacles along Lola's path: after leaving her boozy astrology-fixated mother sitting in

their living room, Lola encounters (1) a snarling dog and a smart-assed kid on the stairway outside their apartment, (2) then a

hot-tempered, down-and-out mother named Doris pushing a baby carriage, (3) a black car driven by her father's associate Herr

Meyer, (4) a crowd of nuns, (5) Mike the bicycle thief, (6) the bum who took Manni's bag, (7) the bank guard Schuster, (8)

Lola's father and his secret lover Jutta, (9) Frau Jäger, a dark-haired woman at the bank, (10) an old woman outside the bank

of whom Lola asks the time, (11) a red ambulance speeding away with its siren blaring, and finally (12) workmen crossing

the street with a large pane of glass, just before meeting Manni at the fateful intersection. As she encounters each of these

human obstacles/potential helpers in each game her actions affect them in some way, and vice versa. Tykwer makes clear the

effect that Lola has on the lives of three of these characters with a fast series of snapshots, accompanied by the sound of a

camera shutter clicking, into that character's possible future following their encounter. Doris, Mike and Frau Jäger are given

this treatment, an odd choice given the very limited verbal interaction Lola has with them. But perhaps not so odd at all:

Tykwer may be suggesting that karmic forces are always at work. Almost trivial interventions into the lives of others can have

monumental consequences. I'll return to these "possible futures" in my synopsis of the film.

The relevance of these encounters is twofold as I see it: Tykwer is appealing to the high cultural theme of causality or karma as driving the events of the film forward, yet at the same time recycling popular culture by making Lola into a computer game character like Lara Croft. As we play each round of a role-playing game like Tomb Raider, we encounter the same obstacles at the same places: a savage warrior behind a given rock, a snarling dog around a specific corner, a hungry shark in the same pool of water. As we hit the replay button each time, we begin to learn when and where each obstacle will appear, and how best to deal with it. Our character may die in Game 1, but in Games 2 and 3 and so on we begin the slow arc toward the goal or center of the game, moving on a spiral learning curve. Tykwer symbolizes this learning process by planting several visual references to spirals in the film: Manni's phone booth is across the street from Spirale bar, with its spinning black and white spiral sign; in the two red interludes we see small spiral patterns on the pillows in Lola and Manni's bed; in several scenes (notably when Lola and Manni are cornered by the police in Game 1), the camera itself spirals into a closeup on the main characters; and finally, the ball on the roulette wheel in Game 3 spirals into the winning number. Again, the spiral symbolizes both a high cultural theme, how we learn to control our fate, while at the same time recycling a pop cultural structure, that of computer games.

Tykwer mixes high and popular culture in his overall aesthetic: his film is structured not only by philosophical motifs like time, causality and fate, but also by colour, by shapes, and by the way the film's soundtrack resonates with the action. It recycles other pop cultural forms both in its overall structure and in its specific images and the way the characters interact with each other, most strongly the computer game and the music video. Let's have a look at the specifics of Tykwer's postmodern pop cultural strategy by means of a synopsis of the film, broken down into the short but important prologue and the three rounds of Lola's karmic game.

Prologue

The brief prologue to the film is absolutely crucial heuristically. In it Tykwer lays his philosophical cards on the table, wasting no time showing us pleasant landscapes or some trivial details of urban life to pass the time as the credits roll. We start with two quotes. The first, from T. S. Eliot's "Little Gidding", tells us that despite all our ceaseless exploring, we'll wind up back where we started, and "know the place for the first time." This evocation of life as a great cycle represents the world-weary modernist version of the game (or perhaps even the ancient Vedic idea of the cycle of birth, death and reincarnation), where all action is a futile exploration of a wasteland that never ends. The second quote, by the German soccer coach S. Herberger, simply says "After the game is before the game." This is clearly the postmodern angst-free reading of life, an invocation to put the ball into play without further adieu even if the game will be repeated time and time again.

The gargoyle clock then ticks away some time, and the scene shifts to a hazy crowd of strangers milling about. The camera picks out the film's secondary characters one by one - they briefly become clear, going from a greyish haze to living colour. Over these images we hear the sonorous voice of the narrator Hans Paetsch describe man as a mysterious species looking for answers to questions like "who are we?", "Where do we come from?", "Where are we going?", "Why do we believe anything at all?" These are all questions driven by modernist angst.

The narrator, clearly a postmodernist, says that even if we could answer one of these questions it will just lead to a new one. It all comes down to a simple conclusion, one that dispenses with all those annoying meta-narratives. As the referee/bank guard announces when his form is made clear to the camera:

No need for big stories here - let's just get the game going, let's play out our own little story. The crowd of strangers, now seen from overhead, then forms the title of the film: "Lola Rennt."The ball is round. The game lasts 90 minutes. That's a fact. Everything else is theory... Here we go! [He kicks a soccer ball into the air]

A cartoon version of a running Lola introduces the people who worked on the film. As each name appears, the cartoon Lola smashes it like a fragile crystal. She also encounters a snarling dog, three clocks, and a spiral. Then comes an entirely different sequence introducing the characters and actors: we hear a camera clicking and see mug shots of the actors from multiple angles flip around with their real and film names listed below, clearly echoing the title screen of a computer game introducing the main characters in a role-playing game. Then we zoom into a satellite photo of Berlin then into Lola's apartment. The game is on.

Game 1 - The Store Robbery

Game 1 - The Store Robbery

In the first game, Lola takes a phone call from Manni about his dilemma. He's a courier for drug runners, who have given him 100,000 marks to deliver to Ronnie, their leader. Lola is late to pick him up because her moped has been stolen, so he takes the subway back. But when he sees some police, he flees the subway car, leaving the bag aboard. A bum steals it and escapes; Manni imagines him vacationing in such exotic locales as Bermuda, Hong Kong and Canada, the screen showing snapshots of postcard-like photos of these places.

Lola and Manni argue on the phone. Manni sees a Bolle grocery market across the road: he'll rob it in 20 minutes unless Lola somehow gets the money to save him. So the game's rules are clear: twenty minutes to find 100,000 marks. As Lola screams in frustration and shatters several bottles, we see a series of visual jokes in her room: a Polaroid of her and Manni embracing, a row of daintily dressed Barbie dolls at odds with Lola's rough-and-tumble physical presence, and a turtle slowly walking across the room, perhaps referring to Zeno's paradox of Achilles and the tortoise.(8)

The camera pans around Lola's head as she asks herself, "Wer? Wer? Wer?" (Who? Who? Who?), trying to figure out from whom she can raise the cash. Again, the camera work echoes video game kinetics. Her musings are ended when a cartoon version of the casino croupier we meet in Game 3 pops up from the bottom of the screen and says "rien ne va plus," no more bets, forcing Lola to put the ball into play.(9) Papa! Is her first answer. Off she goes down the stairs, by the barking dog and smart-assed kid, her first obstacle. She hits Doris the down-and-out mother, who swears at her. This brings us the first of Tykwer's fast collage of snapshots of a minor character's possible future: Doris argues with her husband, becomes an alcoholic, has her baby taken away by social workers, steals a baby from a stroller in the park, and is last seen running away from her pursuers.

At Papa's office, Lola's father is speaking with his mistress Jutta, who wants him to decide between her and his wife. Lola runs through a crowd of nuns, then rejects Mike the bicycle thief's offer of his newly stolen bike for 50 marks. We see one of his possible futures: he's beaten by thugs, winds up in a hospital, and marries a cafeteria cashier he meets there. Mike's role may be yet another cinematic joke, perhaps an ironic reference to Vittorio De Sica's The Bicycle Thief (1948), a central foundation stone in the edifice of post-war Italian neo-realist cinema. Certainly Tykwer is no realist, preferring the hyperreality of the video game to a retelling of dreary tales of unemployment of poverty.

Meanwhile, Lola runs in front of the black car, which then crashes into the white car containing Ronnie and his gangster colleagues. Every action brings forth some sort of reaction - Lola's decisions spin a karmic web that ensnares all those she encounters. She also passes by the bum who took Manni's bag on the subway, oblivious to his role in the drama. In the office, Jutta reveals that she's pregnant. The gatekeeper to her father's office at the bank is the bank guard, also the game's referee. In the first two segments he offers sarcastic remarks upon Lola's arrival, referring to her as "our little princess," while in Game 2 he rebukes her haste by noting that "courtesy and composure are the queen's jewels," ironically comparing Lola's plight with fairy tales of troubled princes and princesses.

Once by the gatekeeper, she runs down the office corridor, encountering a tall woman with dark hair, Ms. Jäger. We see one of her possible futures: a car accident which cripples her, an arduous recuperation, then her suicide by the slitting of her wrist. Lola arrives at her Papa's office and pleads with him for the 100,000 marks. Her father thinks she's crazy: he reveals that he's leaving their family, and that Lola is a "cuckoo's egg," not his natural child. He throws her out. The guard remarks "Well, we all have our bad days," a prescient comment on the fact that Game 1 will fail.

Interspersed with the preceding and following events, we catch glimpses of Manni in a phone booth begging for money from friends, and then preparing to rob the grocery store. Lola runs towards their rendez-vous, passing a red ambulance which slams on the breaks just in front of workmen carrying a large sheet of glass across the street, perhaps symbolic of the fragile nature of life. The glass episode might also be a reference to cartoons: in each segment, we wonder whether the van will hit the glass, shattering it (it happens once, by the way), like the Coyote splattered on the wall of a phoney painted tunnel entrance in a Roadrunner cartoon. Yet whether or not the ambulance hits the glass is clearly connected to previous events in Lola's game, specifically, with Lola's interaction with the driver.

Lola passes a red and white wall sign that looks a bit like a roulette wheel, asking under her breath for Manni to wait for her,

to have faith in her. But he pulls out his pistol and starts the robbery. "Where were you?" he asks as she arrives too late. At this

point we see Lola framed by green and white, Manni by gold and red. Lola shows her commitment to Manni by

clobbering a security guard (who has pulled a gun) with a bag full of bottles. They collect the money from the cash registers in

a red bag, a dangerous colour, and escape to the slow jazzy tune "What a Difference a Day Makes," the only song which is out

of step with the largely techno-rock soundtrack. But they're cornered by the police in the street. Manni throws the bag in the

air, and we see it flip over and over in slow motion, perhaps a reference to the monkey man's bone club in the opening scene of

Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. An inattentive cop shoots Lola by accident in the chest, bringing forth a splattering of blood

and killing her (or so we think).

Lola passes a red and white wall sign that looks a bit like a roulette wheel, asking under her breath for Manni to wait for her,

to have faith in her. But he pulls out his pistol and starts the robbery. "Where were you?" he asks as she arrives too late. At this

point we see Lola framed by green and white, Manni by gold and red. Lola shows her commitment to Manni by

clobbering a security guard (who has pulled a gun) with a bag full of bottles. They collect the money from the cash registers in

a red bag, a dangerous colour, and escape to the slow jazzy tune "What a Difference a Day Makes," the only song which is out

of step with the largely techno-rock soundtrack. But they're cornered by the police in the street. Manni throws the bag in the

air, and we see it flip over and over in slow motion, perhaps a reference to the monkey man's bone club in the opening scene of

Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. An inattentive cop shoots Lola by accident in the chest, bringing forth a splattering of blood

and killing her (or so we think).

In the first of two "red interludes", we see Lola and Manni in bed, filmed though through a red filter lense. Lola wants to know if he loves her. He tells her that he does because she's the best woman in the world. How does he know that? He just feels it, in his heart. Does she want to leave him? She's not sure: she has to decide. This first interlude is about knowledge, faith, and emotional commitment. How do we know we are committed to someone? Does faith have any basis in the world, or just in our feelings, our heart? The question stands unresolved.

Game 2 - The Bank Job

Game 2 - The Bank Job

But the game isn't over yet. Lola doesn't want to leave - she says "stop", and returns to the scene when she tosses her red telephone away. We see her running down the stairs as a cartoon once again, and being tripped by the smart-assed kid. Then we see her in the flesh on her belly at the bottom of the stairs, her cartoon pain having become real. She limps out to a techno song with the lyric "wanna do the right thing," hitting Doris, causing an entirely different future for her - she buys a winning lottery ticket, which brings her a fabulous big white house and happiness: we see her in the final snapshot relaxing in her front yard with her husband and child, a drink in her hand.

Lola's sprained ankle slows her down this time. She passes the nuns, who part into two columns to allow her passage. To add to the oddity of the scene, one of them is wearing sunglasses. Then comes the bicycle thief. Lola rejects his offer with the prescient remark that it's stolen. How does she know? Tykwer might be suggesting that Lola and other characters can somehow learn from past playings of the game. Mike's second possible future sees him going through a slow decline, winding up as a drug addict lying comatose on a washroom floor. Lola runs over the front hood of Meyer's black car, which once again hits the white gangsters' car, this time broadside. Lola then slams into the bum carrying Manni's bag of money, who flees.

In the office, the discussion between Lola's father and his lover Jutta is less pleasant than in Game 1. Jutta confesses that the unborn child may not be his, so they argue over her infidelity. Lola brushes the bank guard aside, entering her father's office at this inconvenient moment. Papa and Jutta resent Lola's interruption: her father tells her to get a job if she wants money, but doesn't mention that she's illegitimate. Lola cries, insults Jutta, then trashes the office, storming out. The guard once again informs her that it's just not her day, perhaps hinting that her karma in Game 2 is on the wane.

This game she tries a new strategy: she grabs the guard's gun and returns to her father's office, taking him hostage (after firing a warning shot). She drags him out of the office to a teller's cage in the front of the bank to demand the 100,000 marks, passing Frau Jäger again in the corridor. We see her second possible future: dinner with the bank teller, some sado-masochistic sex with leathers and a whip, then the two of them as a happy couple walking through a park.

Even though her father warns her that the cops will come soon, Lola perseveres. She waits for the teller to go downstairs to pick up enough cash to make the 100,000. He carefully places the money in a green garbage bag with a gold tie-string. Out the front door she goes, tossing the gun aside - but the police are lined up behind a defensive wall of cars across the street! Surprisingly, they assume she's not the robber and wave her away, a SWAT team cop dressed in black dragging her to safety. Her renunciation of violence and punkish appearance have perhaps saved her.

Lola runs to the intersection where she is to meet Manni while he waits near the phone booth once again. She asks for a ride from the ambulance driver, which distracts him long enough so that he hits the pane of glass being carried across the road by the golden workmen, shattering it dramatically. Manni starts to cross the street, his pistol tucked in his belt, just as a fateful red car passes by him. Lola runs by a wall with a large red arrow on an aqua background (which match her hair and shirt) pointing her way, begging in her mind for Manni to wait for her. Yet in this game she gets there on time - Manni smiles and waves in relief when he sees her. But just then the ambulance arrives, running him over. He lies in the street bleeding, dying. Lola drops the green bag full of the bank's money, shocked.

The second red interlude in bed focuses appropriately on Manni's fear of death. What would Lola do if he were fatally ill? She jokes she'd throw him in the ocean as shock therapy. But seriously? Manni fears she would mourn for a few weeks, then a nice sensitive guy with green eyes (Lola's special colour) would come along and sweep her off her feet with sympathetic words, obliterating any feelings she ever had for Manni. Lola replies "Manni, you haven't died yet," resetting the game once again.

Game 3 - The Casino

Game 3 - The Casino

The third game begins more or less the same way: the money bag and phone fall down in slow motion, Lola runs out the door (in each segment her mother asks her to buy some shampoo), but this time she leaps over the dog and avoids the kid, barking back at them. We hear a techno song playing with the lyric "I wish I were a hunter." Lola seems more self-assured and confident this time, perhaps having learned from her mistakes.

She avoids disgruntled Doris and her baby carriage totally this time, helping to establish an improved karmic atmosphere. In her third possible future, Doris gets religion and becomes a born-again Christian, selling Awake! on the street corner - one might note that the Buddha too wants us to awake, to become enlightened. She runs around the nuns, but hits Mike the bicycle thief, who in his third possible future (seen on videotape) goes to a open-air restaurant, buys some food, and meets the bum with the money bag. "Life's crazy" says the now-wealthy bum, who buys the stolen bike from Mike. Lola flips onto the hood of Meyer's car, pausing there - Meyer recognizes her in this strange encounter, asking her "Is everything OK?" This delay creates a set of domino tumbles distinct from those in Games 1 and 2: it prevents the initial car accident of the previous two games, allows Meyer to arrive at the bank on time for his rendez-vous with Papa, who leave together before Lola gets there, forcing her to rethink her game strategy. Once again, an iron law of causality governs events.

At her father's office, things are also going swimmingly for Papa and Jutta - they're in love, and he agrees to have a baby with her. Yet just before Jutta is going to announce her infidelity, Papa receives a phone call that Meyer has arrived, an arrival made possible by the whole series of events that has happened in Game 3 so far. He leaves the bank jauntily to meet his colleague Meyer, missing Lola entirely. When she finally arrives, the bank guard Schuster says cryptically "You've come at last" in one of the truly uncanny moments in the film. They stare at each other meaningfully, Lola glaring, seeming to exercise something like a magical "wammy"power akin to that given to fantasy game wizards by computer game creators. Schuster's heart starts to pound, hinting at the heart attack to come.

Karmic forces are working better for Lola and Manni this time. As Manni exits the phone booth, he returns a borrowed phone card to a blind woman outside the booth (she was seen in the previous two games, but didn't seem to have any effect on events). This selfless act seems to improve Manni's karma. This time she asks Manni to wait a few seconds, which allows him to catch sight of the bum on his newly bought bike, riding away with Manni's sack of money. It also prevents his being hit by the ambulance, which we see pass by Manni later on. He chases the bum, causing Meyer's black car to swerve away and crash into Ronnie's white car, with Meyer and Papa injured or killed. Right behind them a man on Lola's stolen red moped wearing a white coverall and a black helmet hits the back of the white car, his body flipping over it onto Meyer's car. Once again, the film gives us some good old fashioned Newtonian cause-and-effect collisions, appropriately colour coded according to a dialectic opposition of black and white, with some red death mixed in. One might add that the moped thief is paid back, karmically speaking, for his thievery.

As Lola runs, she asks "What can I do? Help me! I'm waiting," appealing to some sort of inner voice, the gods, or the universe. She's stopped in her tracks by a huge white tanker truck with a green license plate and letters on the fender (Lola's colours). Lola glances across the street to see her salvation: a casino, whose sign consists of huge white letters. She runs inside up a red carpet to a booth where chips can be bought for use in the casino. She only has 99 marks and change, but needs a 100-mark chip - the teller gives it to her, another indicator of positive karma. Once in the main hall of the casino, Lola bets on 20 Black in a roll of the roulette wheel, an obvious reference to the 20-minute time limit of each of the three games. She wins 3,500 marks. In one brief shot we see all the main colours on Tykwer's cinematic palette: the red and black of the wheel's numbers, its gold handles, the green velvet betting table, and green and white chips.

The roulette wheel is no doubt a metaphor for the wheel of fortune, which can bring great success or dismal failure. Its ball spirals into the center of the game, into victory or defeat for the player. Lola lets her money ride on 20 Black again. A well dressed security man tries to evict her, but she asks for "just one more game," another multi-level remark on her fate in the film as a whole. She uses the same "wammy" power she used with the bank guard to cow him into awestruck submission. Lola emits her trademark ear-piercing scream that causes the casino's patrons to cover their ears, their wine glasses smashing. Sure enough, Lola wins again, leaving the casino with the loot she has won with the aid of her fantastic powers, just as a character in a fantasy game uses a magic crystal or a spell to overcome an obstacle. The amazed crowd looks on as she leaves, the camera panning up to a huge clock which shows four minutes to high noon.

Meanwhile, Manni runs after the bum on the bike, threatening him with his gun to stop him. He retrieves his money bag,

giving the bum his gun. The ambulance stops before hitting the glass, and Lola climbs in the back to see a medic frantically

pumping the heart of a man dying from a heart attack: it's the bank guard. The heart monitor is a luminescent green. Lola

holds his hand, giving him hope and faith - his heartbeat becomes regular, amazing the medic. Her green power of nature

triumphs over the red of blood and death.

Meanwhile, Manni runs after the bum on the bike, threatening him with his gun to stop him. He retrieves his money bag,

giving the bum his gun. The ambulance stops before hitting the glass, and Lola climbs in the back to see a medic frantically

pumping the heart of a man dying from a heart attack: it's the bank guard. The heart monitor is a luminescent green. Lola

holds his hand, giving him hope and faith - his heartbeat becomes regular, amazing the medic. Her green power of nature

triumphs over the red of blood and death.

She gets out at the intersection across from the Bolle market, but Manni isn't there. The cars parked along the street are all black and white, except for one red one, another of Tywer's chromatic jokes. Up pulls Ronnie's car. Manni gets out, seemingly once again in Ronnie's good books. He casually announces that everything's OK, asking a surprised-looking Lola if she ran there. She carries a gold bag with her winnings from the casino - a treasure for an uncertain future. The last line in the film is a bemused Manni asking Lola, "what's in the bag?" Then the white credits roll from the bottom of the black screen up as a large red word "ENDE" snakes from right to left over the screen.(10)

Conclusion

Run Lola Run, as we've seen, is a fine piece of postmodern film making. It uses a fast-paced editing style, a techno soundtrack, and a variety of cinematic techniques such as the colour associations mentioned above to place it in a cultural no man's land between computer games, music videos, and traditional action films. On the more superficial level, the film emphasizes style over substance, even though the screenplay gives us a highly structured narrative. We get caught up in the hunt, mesmerized by the film's pace and frenetic style. It also uses pastiche and cultural recycling of non-cinematic forms, notably computer role-playing games like Tomb Raider and Final Fantasy.

Philosophically, the film rejects moral or metaphysical meta-narratives, as the prologue makes clear. As a species, we don't know where we come from or where we're going. Yet we do know one thing: the ball is round, and the game lasts 90 minutes (81 minutes in the film's case). The rest is theory, as the referee announces. In other words, we have a single life to live, and it’s up to us as players to play the game as well as we can.

Yet the core of the film is its hyperreal or virtual aesthetic. Lola is able to replay the fateful twenty minutes of her quest for the treasure that will save Manni's life three times. She appears to learn from mistakes made in previous games, just as a player of a role-playing video game learns where the various traps and obstacles are located in a tomb or ruin they're exploring. This learning process also involves her improving as a person, definitely behaving more altruistically in the third game. Both she and Manni are resurrected once from the dead, not in religious or supernatural terms, but like video game characters - by hitting the reset button.

This idea of repetition can also be linked to not so postmodern ideas, the Buddhist concepts of the great Wheel of Becoming

and of karma.(11) The wheel symbolizes how samsara, sense experience, is forever in flux, and how our failure to escape from

desire, ignorance, and grasping chains us to dukkha, or suffering. Positive actions bring about good karma, while actions which

increase suffering pay us back with bad karma. Yet it's up to us how we spin the wheel of becoming, how we choose a given

set of actions that will have a specific effect on others. And it's clear that Lola's more enlightened decisions in Game 3 help to

improve her karma and thereby allow her to escape from the cycle of death and rebirth, of replaying the same game over and

over again, seen in Games 1 and 2.

This idea of repetition can also be linked to not so postmodern ideas, the Buddhist concepts of the great Wheel of Becoming

and of karma.(11) The wheel symbolizes how samsara, sense experience, is forever in flux, and how our failure to escape from

desire, ignorance, and grasping chains us to dukkha, or suffering. Positive actions bring about good karma, while actions which

increase suffering pay us back with bad karma. Yet it's up to us how we spin the wheel of becoming, how we choose a given

set of actions that will have a specific effect on others. And it's clear that Lola's more enlightened decisions in Game 3 help to

improve her karma and thereby allow her to escape from the cycle of death and rebirth, of replaying the same game over and

over again, seen in Games 1 and 2.

In the film Lola is caught up in a great wheel of fate, as symbolized by the roulette wheel in Game 3. This is foreshadowed by the scenes in Game 1 when the camera spins around her head as she runs through in her mind people she can ask for the money, and later when she runs by a large red-and-white poster on a wall that looks like either a circle of triangles on a roulette wheel or the Imperial Japanese war ensign. Her actions change each time, influencing those she encounters, even if it's only fleetingly. And sometimes the changes she brings about are dramatic: Mike the bicycle thief goes from marriage to hopeless drug addiction between Games 1 and 2, while Doris shifts from an alcoholic stupor to a big lottery win in the same transition. Life's crazy, as Norbert von Au, the comically named bum, tells us. In the end she wins her karmic video game, carrying away her bag of gold in one hand, holding Manni's hand with the other. Just as she fantastically beats the roulette game twice, in the end she earns a double victory, gaining both wealth and love. Run Lola Run is thus the first combination computer game/music video/karmic action film, surely something worth taking note of.

Bibliography - Films, Videos and Computer Games

Superman. Directed by Richard Donner. Characters created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster. Written by Mario Puzo, David Newman, Leslie Newman and Robert Benton. 1978.

Batman. Directed by Tim Burton. Characters created by Bob Kane. Story by Sam Hamm. Screenplay by Sam Hamm and Warren Skaaren. 1989.

Batman Returns. Directed by Tim Burton. Characters created by Bob Kane. Story by Daniel Waters and Sam Hamm. Screenplay by Daniel Waters. 1992.

Batman Forever. Directed by Joel Schumacher. Characters created by Bob Kane. Story by Lee Batchler and Janet Scott Batchler. Screenplay by Lee Batchler, Janet Scott Batchler and Akiva Goldsman. 1995.

Batman and Robin. Directed by Joel Schumacher. Characters created by Bob Kane. Written by Akiva Goldsman. 1997.

X-Men. Directed by Bryan Singer. Story by Tom DeSanto and Bryan Singer. Screenplay by David Hayter. 2000.

X2. Directed by Bryan Singer. Story by Bryan Singer, David Hayter and Zak Penn. Screenplay by Michael Dougherty and Daniel P. Harris. 2003.

Spider-Man. Directed by Sam Raimi. Comic book by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko. Written by David Koepp. 2002.

Daredevil. Written and Directed by Mark Steven Johnson. 2003.

Hulk. Directed by Ang Lee. Comic book by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Written by John Turman, Michael France and James Schamus. 2003.

Lara Croft: Tomb Raider. Directed by Simon West. Story by Sara B. Cooper, Mike Werb and Michael P. Colleary. Adaptation by Simon West. Screeplay by Patrick Massett and John Zinman. 2001.

Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within. Directed by Hironobu Sakaguchi and Moto Sakakibira. Story by Hironobu Sakaguchi. Written by Al Reinert and Jeff Vintar. 2001.

Run Lola Run. Written and directed by Tom Tykwer, 1998.

Adventures of Superman. TV series starring George Reeves as Superman, 1952-1957.

Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman. TV series, 1993-1997.

Smallville. TV series on the life of young Clark Kent, 2001-now.

Spider-Man. Animated TV series. Written by Ralph Bakshi. Directed by Ralph Bakshi and various others.1967-1970.

Game Over! Gender, Race & Violence in Video Games (instructional video). Produced and Directed by Nina Huntemann. Northampton, Mass.: Media Education Foundation, 2000.

Tomb Raider III: Adventures of Lara Croft (computer game). Core Design/Eidos Interactive, 1998.

Tomb Raider IV: The Last Revelation (computer game). Core Design/Eidos Interactive, 1999.

Bibliography - Print Sources and Websites

Baudrillard, Jean. "The Precession of the Simulacra." Simulacra and Simulation. Trans. Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Koller, John M. and Patricia Joyce Koller. Asian Philosophies. 3rd Edition. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall, 1998.

Overstreet, Robert M. Official Comic Book Price Guide. 21st edition. New York: The House of Collectibles, 1991.

Strinati, Dominic. An Introduction to Theories of Popular Culture. London: Routledge, 1995.

Whelan, Tom. "Run Lola Run." Film Quarterly 53.3 (Spring 2000): 33-40.

Wright, Bradford. Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Comic Books (most of these series have spin-offs)

Action Comics/Superman (DC Comics, 1938/1939 and on)

Detective Comics/Batman (DC Comics, 1939/1940 and on)

The Amazing Spiderman (Marvel Comics Group, 1963 and on)

Daredevil (Marvel Comics Group, 1964 and on)

The X-Men (Marvel Comics Group, 1963 and on)

Websites on Lara Croft

Official game site (loaded with graphics): http://www.tombraider.com/

Eidos Interactive site (features descriptions of all the games in the Tomb Raider series, which as of the summer of 2003 includes six major titles and a few add-ons): http://www.eidosinteractive.com/home.html

Core Design site: http://www.core-design.com

"Lara Croft," Croft 2000 website: http://croft-2000.freeservers.com/lara.html

Birgit Pretzsch, "Lara Croft and Feminism," based on her Master's thesis "A Postmodern Analysis of Lara Croft: Body, Identity, Reality": http://www.frauenuni.de/students/gendering/lara/home.html

1. Dominic Strinati, in his An Introduction to Theories of Popular Culture (London: Routledge, 1995), argues that there has been relatively little said about postmodernism as an empirical or historical phenomenon (p. 222). Strinati outlines five distinctive qualities of postmodern popular culture: 1. The breakdown of the distinction between culture and society (which I have re-titled the coming of a hyperreal media culture), 2. The breakdown of the distinction between art and popular culture, 3. An emphasis on style over substance, 4. Confusions over time and space (to which I would add the eclipse of history), and 5. The decline of meta-narratives. I agree with his typology, but would add two more elements: 6. The eclipse of the new (parody, pastiche, self-referencing and recycling as dominant narrative tropes), and 7. The death of the author and the fragmenting of the self. Qualities 4 and 7 will not be dealt with in this paper.