Meeting 3: Michael Francis

Back to seminar page

More on group von Neumann algebras

Let $\Gamma$ be a discrete group. Let $\lambda$ and $\rho$ be the left and right regular representations of $\Gamma$ on $\ell^2(\Gamma)$ determined on the standard basis $(e_g)_{g \in \Gamma}$ by

$$\begin{array}{cccc} \lambda_g e_h= e_{gh} &&& \rho_g e_h = e_{hg^{-1}} \end{array}.$$

The von Neumann double-commutant theorem tells that, given a $*$-closed set $S \subseteq \mathbb{B}(H)$, there are two equivalent ways to describe the von Neumann algebra generated by $S$: the weak (or strong, or ultraweak, or ultrastrong) closure of the $*$-algebra generated by $S$, or the double commutant $S''$. Accordingly, we have two equivalent ways of defining the left group von Neumann algebra $vN_\lambda(\Gamma)$ or right group von Neumann algebra $vN_\rho(\Gamma)$.

Description 1:

- $vN_\lambda(\Gamma)$ is the wot-closure of all finite $\mathbb{C}$-linear combinations $\sum_{i=1}^n c_{g_i} \lambda_{g_i}$.

- $vN_\rho(\Gamma)$ is the wot-closure of all finite $\mathbb{C}$-linear combinations $\sum_{i=1}^n c_{g_i}\rho_{g_i}$.

Description 2:

- $vN_\lambda(\Gamma) = \lambda(\Gamma)''$

- $vN_\rho(\Gamma) = \rho(\Gamma)''$

Since the left and right regular representations commute, we have the von Neumann algebra containments

$$\begin{array}{cccc}

vN_\lambda(\Gamma) \subseteq \rho(\Gamma)' = vN_\rho(\Gamma)'&&& vN_\rho(\Gamma) \subseteq \lambda(\Gamma)' = vN_\lambda(\Gamma)' \end{array}$$

One naturally suspects these containments to be equalities, and indeed they are.

Theorem 3.1: $vN_\lambda(\Gamma)$ and $vN_\rho(\Gamma)$ are commutants of each other.

Interestingly, if we attempt to use Description 1 to prove this, things become rather problematic. On the other hand, if we use Description 2, this turns out to be rather easy. Thus, the above the theorem is a very nice demonstration of the power of the von Neumann double-commutant theorem. Starting from Description 2, one sees (after a little thought) that the thing to prove is precisely the following claim:

Claim: The von Neumann algebras $\rho(\Gamma)'$ and $\lambda(\Gamma)'$ commute with one another.

Let's describe the algebras in the claim a bit better. To say $T \in \mathbb{B}(\ell^2(\Gamma))$ belongs to $\rho(\Gamma)'$ is to say that

$$ \langle T e_{h_1}, e_{h_2} \rangle = \langle \lambda_g T {\lambda_g}^* e_{h_1},e_{h_2} \rangle = \langle T e_{h_1g},e_{h_2g}\rangle$$

for all $g,h_1,h_2 \in \Gamma$, which amounts to saying that

the matrix of $T$, viewed as a function $\Gamma \times \Gamma \to \mathbb{C}$, is constant along each part of the partition $\bigsqcup_{h \in \Gamma} \{ (hg,g) : g \in \Gamma \}$ of $\Gamma \times \Gamma$ into "diagonals". Note, however, that the matrix of $\lambda_h$ is precisely equal to the characteristic function of the "diagonal" $\{ (hg,g) : g \in \Gamma \}$, and so an operator $T \in \mathbb{B}(\ell^2(\Gamma))$ belongs to $\rho(\Gamma)'$ if and only if it can be expressed as a formal sum

$$ T = \sum_{g \in \Gamma} c_g \lambda_g$$

where the summation should only be interpreted as a formula for the matrix of $\mathbf{T}$. The point is just that a function which is constant on every part of a partition can, formally, be encoded by infinite linear combination of characteristic functions of the parts.

By a similar discussion, the $S \in \lambda(\Gamma)'$ are precisely the bounded operators on $\ell^2(\Gamma)$ whose matrix can be expressed as a formal sum $S = \sum_{g \in \Gamma} c_g \rho_g$. Now we return to the

Proof of the claim: Let $S = \sum_{g \in \Gamma} a_g \rho_g \in \lambda(\Gamma)'$ and $T = \sum_{g \in \Gamma} b_g \lambda_g \in \rho(\Gamma)'$ be given (sums are formal). We want to show that $ST=TS$, which will follow from

$$\langle ST e_{h_1},e_{h_2}\rangle = \langle TS e_{h_1},e_{h_2} \rangle$$

for all $h_1,h_2 \in \Gamma$. By writing $T = \lambda_{h_2} T_0\lambda_{{h_1}^{-1}}$ where $T_0 \in \rho(\Gamma)'$ too, we may reduce to establishing this in the case $h_1=h_2=1$. So, the thing to prove is just

$$ \langle T e_1, S^* e_1 \rangle = \langle S e_1 ,T^* e_1 \rangle $$

where, from knowledge of the matrices,

$$\begin{array}{cccc}

Se_1 =\sum_{g \in \Gamma} a_g e_g &&& S^* e_1 = \sum_{g \in \Gamma} \overline{a_{g^{-1}}} e_g \\ Te_1 = \sum_{g \in \Gamma} b_g e_g &&& T^*e_1=\sum_{g\in\Gamma} \overline{b_{g^{-1}}} e_g \end{array}$$

and so

$$\langle T e_1, S^* e_1 \rangle= \sum_{g\in\Gamma} b_g a_{g^{-1}} = \sum_{g \in \Gamma} a_g b_{g^{-1}} = \langle S e_1 ,T^* e_1 \rangle$$

as desired. $\square$

Now we are in a rather unusual predicament.

- We have shown that $vN_\lambda(\Gamma)$ equals all the bounded operators $T$ which can be expressed as formal sums $T = \sum_{g \in \Gamma} c_g \lambda_g$.

- On the other hand, according to Description 1, $vN_\lambda(\Gamma)$ equals all bounded operators which can be expressed as wot-limits of finite sums $\sum_{i=1}^n c_{g_i} \lambda_{g_i}$.

Based on these two points, it is very reasonable to believe that a bounded operator which is defined by a formal sum $\sum_{g \in \Gamma} c_g T_g$ should be equal to the wot-limit of finite partial sums $\sum_{g \in F} c_g T_g$ as $F$ ranges over finite subsets of $\Gamma$. In principal, $T$ is the limit of some net of finite sums, so surely its net of finite partial sums should do the job? Unfortunately, this is generally false and is, apparently, a commonly occurring mistake in the literature, even appearing such standard tomes as C*-Algebras and their Automorphism Groups by Pedersen and Theory of Operator Algebras: I by Takesaki.

An in-depth discussion of this misconception can be found in the paper Convergence of Fourier Series in Discrete Crossed Products of von Neumann Algebras by Mercer. As the title of the article would suggest, the basic reason why this type of convergence fails has to do with Fourier series. So, to see what goes wrong, we should consider $\Gamma=\mathbb{Z}$. Under the Fourier transform $\ell^2(\mathbb{Z}) \to L^2(\mathbb{T})$, the group von Neumann algebra $vN(\mathbb{Z})$ is sent to $L^\infty(\mathbb{T})$, represented as multiplication operators. The convergence question amounts to "does the Fourier series $\sum_{n \in \mathbb{Z}} \widehat f(n) z^n$ of a function $f \in L^\infty(\mathbb{T})$ converge to $f$ in the weak operator topology?" It is quite easy to see that the weak operator topology on $L^\infty(\mathbb{T}) \subseteq \mathbb{B}(L^2(\mathbb{T}))$ coincides with the weak-star topology coming from the identification $L^\infty(\mathbb{T})=(L^1(\mathbb{T}))^\text{dual}$. Weak-star topologies have the rather nice feature that a necessary condition for convergence of a net is boundedness of the net. The latter is a consequence of the uniform boundedness principal: if a net of functionals is unbounded, it blows up at some point, hence cannot converge weak-star. So, all we need to do to get a counterexample is find an $f \in L^\infty(\mathbb{T})$ the partial sums of whose Fourier series $\sum_{n \in \mathbb{Z}} \widehat f (n) z^n$ are not bounded in the $\infty$-norm. It is well-known that such things can happen. Indeed, there exist continuous functions $f \in C(\mathbb{T})$ whose Fourier series blow up on a dense $\mathscr{G}_\delta$ set of a points.

Comparison theory for projections

Let $e$ and $f$ be projections in a C*-algebra $A$. We say write $e \leq f$ and say $e$ is a subprojection of $f$ if $ef=e$. When we are represented on a Hilbert space, this just means the subspace associated to $e$ is contained in the subspace associated to $f$. We write $e \sim_{MvN} f$ and say that $e$ is Murray-von Neumann equivalent to $f$ in $A$ if there exists a parital isometry $w \in A$ such that $w^*w=e$ and $ww^* = f$. It's easily checked that this is an equivalence relation. When we are represented on a Hilbert space, this just means that the algebra $A$ contains a partial isometry mapping the subspace associated to $e$ isometrically onto the subspace associated to $f$. We write $e \preceq f$ and say that $e$ is subequivalent to $f$ if $e' \leq f$ for some $e'$ Murray von Neumann equivalent to $e$. It's easily checked that $\preceq$ is reflexive and transitive.

It is worth keeping in mind that comparison of projections is very much analogous to comparing cardinalities of sets. We say that $|X| = |Y|$ when there is a bijection between two sets $X$ and $Y$. We say that $|X| \leq |Y|$ when there is a bijection from $X$ onto a subset of $Y$.

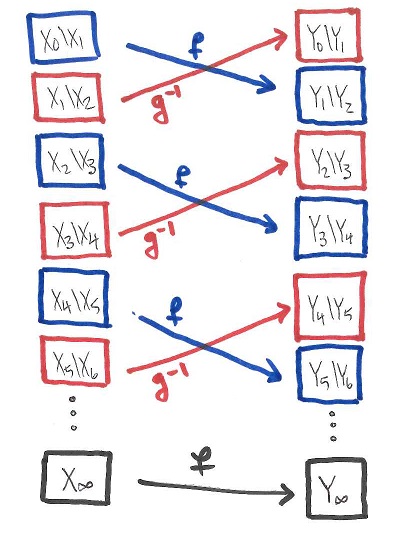

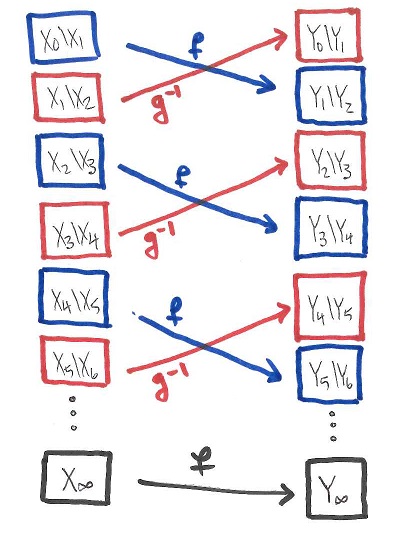

The usefulness of cardinal arithmetic depends on (among other things) the fact that, if $|X| \leq |Y|$ and $|Y| \leq |X|$, then $|X|=|Y|$. That is, if there are is a bijection $f$ from $X$ onto a subset $Y_1$ of $Y$ and also a bijection $g$ of $Y$ onto a subset $X_1$ of $X$, then there is a bijection $\Phi : X \to Y$. This fact goes by the name of the Schroeder-Bernstein Theorem. It does not depend on the axiom of choice; the bijection $\Phi$ can be be obtained by an explicit back-and-forth construction. Define sequences of nested subsets $X \supseteq X_1 \supseteq X_2 \supseteq \ldots \supseteq X_\infty$ and $Y \supseteq Y_1 \supseteq Y_2 \supseteq \ldots \supseteq Y_\infty$ as follows:

$$\begin{array}{llll}

X_{i+1} = g(Y_i) &&& Y_{i+1} = f(X_i) & i \geq 1\\

&&&&\\

X_\infty = \bigcap_{i=0}^\infty X_i &&& Y_\infty = \bigcap_{i=0}^\infty &

\end{array}$$

With these definitions, one observes

- $f$ maps $X_i$ bijectively onto $Y_{i+1}$

- $g$ maps $Y_i$ bijectively onto $X_{i+1}$

- $f$ maps $X_\infty$ bijectively onto $Y_\infty$

and then defines a bijection $X \to Y$ as indicated in the following diagram.

Comparing projections is worthwhile the von Neumann algebra context because we have a kind of Schroeder-Bernstein theorem:

Theorem 3.2: If $e$ and $f$ are projections in a von Neumann algebra $M$ and $e \preceq f$ and $f \preceq e$, then $e \sim_{MvN} f$.

This theorem is proved by exactly following the template of the set-theoretic Schroeder-Bernstein theorem to produce a whole bunch of partial isometries between a whole bunch of mutually orthogonal subprojections of $e$ and $f$, and then adding them all together (using weak closedness!!) to get partial isometry between the total projections. Theorem 3.2 says that the Murray-von Neumann equivalence classes of projections a von Neumann algebra $M$ are partially ordered by subequivalence. If $M$ is a factor, then the analogy with set theory becomes even closer: the law of trichotomy holds.

Theorem 3.3: Let $e$ and $f$ be projections in a von Neumann algebra $M$. If $M$ is a factor, then either $e \preceq f$ or $f \preceq e$ holds.

This is proved exactly along the lines of the corresponding statement in set theory. To show that, given two sets $X$ and $Y$, there is either a bijection from $X$ to $Y$, or a bijection from $Y$ to $X$, we partially order all "partial bijections" from a subset of $X$ to a subset of $Y$ by the relation "extends", and then use Zorn's lemma to produce a maximal one $\Phi$. If $\Phi$ does not have either $\mathrm{dom}(\Phi)=X$ or $\mathrm{ran}(\Phi)=Y$, we will be able to extend it further.

We can basically apply exactly this strategy to a pair of projections $e$ and $f$. We consider all partial isomeries going from subprojections of $e$ to subprojections of $f$, and partially order them in the obvious way. We then use Zorn's lemma to extract a maximal such partial isometry $w$ (this uses weak closedness to take a supremum). In the event that neither $w^*w=e$ nor $ww^*=f$ holds, we need to be sure that we can extend a little bit further by adding on a nonzero partial isometry between the leftover subprojections of $e-w^*w$ and $f-ww^*$. This is the point where the assumption that $M$ is a factor becomes important. The key thing is the following "Ergodic lemma", which tells that, up to Murray-von Neumann equivalence, any two nonzero projections overlap on a nonzero projection.

Lemma 3.4: If $e$ and $f$ are any two nonzero projections in a factor $M$, then there exist nonzero subprojections $e' \leq e$ and $f' \leq f$ such that $e' \sim_\text{MvN} f'$.

Proof: If $ef \neq 0$, this is easy. The point is that $x=ef$ is supported on $f$ and has range contained in $e$ so, when we write $x=w|x|$ (polar decomposition) the partial isometry $w$ from $\mathrm{supp}(x)$ to $\overline{\mathrm{ran}}(x)$ implements a Murray-von Neumann equivalence from a subprojection of $f$ to a subprojection of $e$. Here it is important that $M$ is a von Neumann algebra, in order to be sure that $w \in M$ (in the C*-algebra context, the partial isometry in a polar decomposition can fall outside of the algebra).

If $ef=0$, we need to use that $M$ is a factor. We claim that $ueu^* f \neq 0$ for some unitary $u \in M$. Once $u$ is found, we are done because we can replace $e$ by the Murray-von Neumann equivalent projection $ueu^*$ and use the argument of the first paragraph. Such a unitary must exist. If this were not the case, then the supremum $\overline e = \bigvee_{v \in \mathcal{U}(M)} v e v^*$ would be a nonzero (because it contains $e$), central (because it commutes with every unitary) and proper (because it is orthogonal to $f$) projection, contradicting the assumption that $Z(M) =\mathbb{C}$. $\square$

The conclusion is that, associated to any factor $M$, one has a canonical totally ordered set---Namely, the Murray-von Neumman equivalence classes of projections in $M$, totally ordered by subequivalence. We state what is this total order in two examples.

- If $M=\mathbb{B}(H)$, for $H$ a separable infinite dimensional Hilbert space, we get $\{0,1,2,3,\ldots,\infty\}$, since two projections are Murray von Neumann equivalent if and only if they have the same dimension.

- If $M = vN(F_2)$, the von Neumann algebra of the free group $F_2$ on two generators, then the total order obtained is isomorphic to $[0,1]$. The way to see this is to calculate the trace on projections (Example 3.3.10 in Vaughan Jones's notes). Note that two Murray-von Neumann equivalent projections necessarily have the same trace. Also, the trace is faithful so that, if $e$ is a proper subprojection of $f$, then $\tau(e) < \tau(f)$.

Back to seminar page