Women Intellectuals of 18th Century Germany

While much of German intellectual life in the 18th century was driven by the university (and the men who held academic positions there), women contributed in a number of crucial ways to the contemporary intellectual culture. While some exercised an indirect influence through the organization of the popular literary salons, a number were able to establish themselves as important scholars, translators, and popularizers, some through drawing on their connections to prominent male relations, and still others actively sought to break down the barriers facing women in academia. Though they are largely excluded from the Enlightenment canon, and suffer from a lack of attention even in comparison with their French and British counterparts (with few of their works translated into English), the works catalogued in this database are certainly deserving of wider philosophical consideration, as indeed the history of 18th century Germany thought cannot be told without acknowledging the key roles that these women played.

I am grateful to Brian Bradley Ohlman for his work on constructing this archive, and to Falk Wunderlich for his assistance in compiling the names for the catalogue. I am also grateful to the Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen Anhalt for their assistance in digitizing texts. For suggestions, additions, or comments on this database, please contact Corey W. Dyck.

Albrecht, Sophie (1757-1840)

Source: Wikipedia

- Primary

-

- Gedichte und Schauspiele (1781)

- Das höfliche Gespenst

- Aramena, eine Syrische Geschichte ganz für unsre Zeiten umgearbeitet (1782)

- Gedichte und prosaische Aufsätze (1785)

- Graumännchen oder Die Burg Rabenbühl : Eine Geistergeschichte altteutschen Ursprungs (1799)

- Ida von Duba, das Mädchen im Walde. Eine romantische Geschichte (1805)

- Friedrich Clemens Gerke (Ed.): Anthologie aus den Poesien von Sophia Albrecht (1841)

- Secondary

-

- “Gedichte und prosaische Aufsätze von Sophie Albrecht. Zweyter Theil.” Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, 1785. Bd. 1, Nm. 59. 248. (1785)

- Review of volume 2 of Poetry and Prose Essays

- “Gedichte und prosaische Aufsätze von Sophie Albrecht. Dritter Theil.” Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, 1792. Bd. 1, Nm. 28. 220-22. (1792)

- Review of volume 3 of Poetry and Prose Essays

- Further reading

-

- Dawson, Ruth P. The Contested Quill: Literature by Women in Germany, 1770-1800. University of Delaware Press, 2002.

- "Johanne Sophie Dorothea Albrecht." In: Wilson, Katharina M. An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers. Vol. 1. Taylor & Francis, 1991. 19-20.

- Dawson, Ruth P. "Reconstructing Women's Literary Relationships: Sophie Albrecht and Female Friendship." In: In the Shadow of Olympus: German Women Writers Around 1800. Eds. Katherine Goodman and Edith Waldstein. Albany: SUNY Press, 1992. 173-188.

Baldinger, Dorothea Friedrica (1739-1786)

- Primary

-

- Schreiben an die Herausgeber des Magazins (1782)

- Magazin für Frauenzimmer, Jahrgang 1 (1782), Band 2, 825ff.

- Über das alte Schloß Pless (*), bei Göttingen. Ein Brief vin Madame *** an H. K. in C (1782)

- Magazin für Frauenzimmer, Jahrgang 2 (1782), Band 1, 179-186.

- Ermahnungen einer Mutter, an ihre Tochter. Am Confirmationstage (1783)

- Magazin für Frauenzimmer, Jahrgang 2 (1783), Band 2, 99-103.

- Lebensbeschreibung von Frederika Baldinger von ihr selbst verfaßt (Offenbach: Weiß u. Brede, 1791)

- Reprinted in: "Ich wünschte so gar gelehrt zu werden." Drei Autobiographien von Frauen des 18. Jahrhunderts. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 1994.

- Correspondence

-

- Letters to Abraham Gotthelf Kästner

- Cod. Ms. philos. 166:149. Staats- und Universitätsbibliotek, Göttingen.

- Letters to Sophie La Roche

- 31 January 1786, 16 May 1783, 23 November 1785. La Roche 56/I,4,16. Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv, Weimar.

- Letters

- Magazin für Frauenzimmer. Strassburg 1783, 1: 179-186, and 2: 99-103.

- Secondary

-

- Anon. "Kleine Schriften," Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, 1792. Bd. 1, Nm. 7. 615. (1792)

- Review of the Lebensbeschreibung

- Further reading

-

- Dawson, Ruth P. The Contested Quill: Literature by Women in Germany, 1770-1800. University of Delaware Press, 2002.

- "Baldinger, Dorothea Friedrica." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 1. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 49.

Bandemer, Susanne von (1751-1828)

Source: Neue vermischte Gedichte (Berlin, 1802)

- Primary

-

- Poetische und prosaische Versuche (1787)

- Sydney und Eduard, oder was vermag die Liebe? (1792)

- Klara von Bourg, eine wahre Geschichte aus dem letzten Zehnteil des abscheidenden Jahrhunderts (1798)

- Edmund Knapp, oder die Wiedervergeltung (Frankfurt, 1800)

- Neue vermischte Gedichte (Berlin, 1802)

- Further reading

-

- "Bandemer, Susanne von." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 1. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 50-1.

- Chlewicka, Katarzyna. 'Uns ist die Kunst nur schöner Zeitvertreib'. Leben und Schaffen Susanne von Bandemers (1751-1828). Der Andere Verlag, 2010.

Clodius, Julie (née Stölzel) (1755-1805)

Source: Wikipedia

- Primary

-

- Eduard Montrefrevil (1806)

- Translated

-

- Gedichte von Elisa Carter und Charlotte Smith (1784)

- Further reading

-

- "Christian August Clodius." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 1. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 206-7.

Cochois, Babette (1725-1780)

Portrait by Antoine Pesne, 1750.

Source: Wikipedia

- Further reading

-

- "Argens, Jean-Baptiste de Boyer." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 1. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 32-4.

Ehrmann, Marianne (1755-1795)

- Primary

-

- Müssige Stunden eines Frauenzimmers (1784)

- Anonymous

- Philosophie eines Weibs: Von einer Beobachterin (1784)

- Leichtsinn und gutes Herz oder die Folgen der Erziehung. Ein Original-Schauspiel in fünf Aufzügen (1785)

- as Maria Anna Antiona Sternheim

- Amalie and Minna (1787)

- Amalie: Eine wahre Geschichte in Briefen (1788)

- Amaliens Erholungsstunden (1788)

- Graf Bilding: Eine Geschichte aus dem mittleren Zeitalter (1788)

- Die Einsiedlerinn aus den Alpen (1790-1792)

- Amaliens Feierstunden (1796)

- Further reading

-

- Dawson, Ruth P. The Contested Quill: Literature by Women in Germany, 1770-1800. University of Delaware Press, 2002.

- "Marianne Ehrmann." In: Wilson, Katharina M. An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers. Vol. 1. Taylor & Francis, 1991. 364-5.

- Holden, Anca L. "Marianne Ehrmann's Ein Weib ein Wort -- A Platform for Moral Education." In: Challenging Separate Spheres: Female Bildung in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Germany. Noth American Studies in 19th-Century German Literature, Vol. 40. Ed. Marjanne E. Goozé. Bern: Peter Lang, 2007. 33-50.

- Kirsten, Britt-Angela. Marianne Ehrmann: Publizistin und Herausgeberin in ausgehenden 18. Jahrhundert. Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag, 1997.

- Stipa, Helga Madland. Marianne Ehrmann. Reason and Emotion in Her Life and Works. Peter Lang, 1998.

Engelhard, Philippine (née Gatterer) (1756-1831)

Source: Wikipedia

- Primary

-

- Aus der Brieftasche eines Frauenzimmers (Strasbourg, 1782)

- In: Magazin für Frauenzimmer. Neuntes Stück. Herbstmonat. 724–734.

- Gedichte. Zwote Sammlung. Mit 4 Kupfern (Göttingen, 1782)

- Neujahrs-Geschenk für liebe Kinder (Cassel, 1787)

- Neue Gedichte. Dritte Sammlung (Nürnberg, 1821)

- Translated

-

- Pierre-Jean de Béranger: Lieder. Nach dem Französischen treu übersetzt von Philippine Engelhard geborene Gatterer (Cassel, 1830)

- Correspondence

- Further reading

-

- Dawson, Ruth P. The Contested Quill: Literature by Women in Germany, 1770-1800. University of Delaware Press, 2002.

- "Philippine Engelhard." In: Wilson, Katharina M. An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers. Vol. 1. Taylor & Francis, 1991. 378-9.

Erxleben, Dorothea Christiane (née Leporin) (1715-1762)

Source: Wikipedia

- Primary

-

- Gründliche Untersuchung der Ursachen, die das weibliche Geschlecht vom Studieren abhalten (1742)

- Quod nimis cito ac iucunde curare saepius fiat caussa minus tutae curationis. Dissertation. (1754)

- Academische Abhandlung von der gar zu geschwinden und angenehmen, aber deswegen oefters unsicheren Heilung der Krankheiten (1754)

- Reprinted: Verlag Janos Stekovics, Dößel, 2004

- Further reading

-

- "Erxleben, Dorothea Christiane." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 1. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 287-9.

- O'Neill, Eileen. “Disappearing Ink: Early Modern Women Philosophers and Their Fate in History." In: Philosophy in a Feminist Voice. Ed. Janet A. Kourany. Princeton UP, 1998. 17-62.

Forkel-Liebeskind, Meta (1765-1853)

- Primary

-

- Originalbrief einer Mutter von achtzehn Jahren an eine Freundin, als diese ihr nach der Niederkunft zum erstenmal geschrieben hatte (1783)

- (Anonymous) In: Hannoversches Magazin, 101tes Stück, Freitag, den 19ten Dezember 1783, Sp. 1609-1612.

- Maria. Eine Geschichte in Briefen (Leipzig, 1784)

- (Anonymous)

Gallitzin, Amalia Fürstin von (1748-1806)

Source: Wikipedia

- Correspondence

- Further reading

-

- "Gallitzin, Amalia Fürstin" In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 1. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 369-71.

Gottsched, Luise Adelgunde Viktorie (1713-1762)

Portrait by Anton Graff, 1792

Source: Wikipedia

- Primary

- Correspondence

-

- Briefe der Frau Louise Adelgunde Victorie Gottsched geboren Kulmus (1771-76)

- Louise Gottsched − ‘mit der Feder in der Hand.’ Briefe aus den Jahren 1730–1762, ed. Inka Kording (Darmstadt, 1999)

- Further reading

-

- "Luise Adelgunde Victoria Gottsched." In: Wilson, Katharina M. An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers. Vol. 1. Taylor & Francis, 1991. 476-8.

- "Gottsched, Luise Adelgunde Viktorie." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 1. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 426.

Herbert, Maria von (1769-1803)

- Correspondence

-

- Letter 478, from Fräulein Maria von Herbert to Kant, August 1791. AA 11: 273-274.

- Letter 510, from Kant to Fräulein Maria von Herbert (draft), Spring 1792 (?). AA 11: 331-334.

- Letter 554, from Maria von Herbert to Kant, January 1793. AA 11: 400-403.

- Letter 614, from Maria von Herbert to Kant, Beginn of 1793. AA 11: 484-486.

-

Further reading

- .

- Baum, Wilhelm (ed.). Weimar – Jena – Klagenfurt: Der Herbert-Kreis und das Geistesleben Kärntens im Zeitalter der Französischen Revolution. Kärntner Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft, Klagenfurt, 1989.

- Baum, Wilhelm. "Der Klagenfurter Herbert-Kreis zwischen Aufklärung und Romantik." In Revue internationale de philosophie; Vo. 3, 1996, 483–514.

- Benjamin, Walter. "Unbekannte Anekdoten von Kant." In Gesammelte Schriften; Vol. IV, 2. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt a/M, 1972, 808–815.

- Forberg, Carl Friedrich. "Lebenslauf eines Verschollenen" (1840), reprinted in Philosophische Schriften, vol. 1 ed. Guido Naschert (forthcoming).

- George, Rolf. "Langton on duty and desolation". In: Kantian Review, Volume 14/1 (2009), S. 123-128.

- Langton, Rae. "Duty and Desolation". In: Philosophy, volume 67 (1992), pp. 481-505.

- Mahon, James Edwin. "Kant and Maria von Herbert: Reticence vs. Deception". In: Philosophy, volume 81 (2006), S. 417-44.

- Markovits, Julia. Moral Reason. Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Ortner, Max. "Kant in Kärnten." In: Carinthia I, 1924, 65–87.

- Sauer, Werner. "Der Herbert-Kreis." In Österreichische Philosophie zwischen Aufklärung und Restauration: Beiträge zur Geschichte des Frühkantianismus in der Donaumonarchie. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg; Rodopi, Amsterdam, 1982, 231–265.

Holst, Amalia (1764-1847)

- Primary

- Further reading

-

- "Holst, Amalia." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 2. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 544-6.

- Sotiropoulos, Carol Strauss. Early Feminists and the Education Debates: England, France, Germany 1760-1810. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2007.

Huber, Therese (1764-1829)

- Primary

-

- Abentheuer auf einer Reise nach Neu-Holland. "Teutschlands Töchtern geweiht" (Tübingen, 1793)

- Die Familie Seldorf. Eine Geschichte (Tübingen 1795/96)

- Luise – oder ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Konvenienz (Leipzig, 1796)

- Erzählungen (Braunschweig, 1801–02)

- L. F. Hubers sämtliche Werke seit dem Jahr 1802, nebst seiner Biographie (Tübingen, 1806–19)

- Bemerkungen über Holland - aus dem Reisejournal einer deutschen Frau (Leipzig, 1811)

- Hannah, der Herrnhuterin Doborah Findlig (Leipzig, 1821)

- Ellen Percy, oder Erziehung durch Schicksale (Leipzig, 1822)

- Johann Georg Forsters Briefwechsel. Nebst einigen Nachrichten von seinem Leben (Leipzig, 1829)

- Die Ehelosen (Leipzig, 1829)

- Die Weihe der Jungfrau bei ihrem Eintritt in die größere Welt (Leipzig, 1831)

- Erzählungen von Therese Huber (Leipzig, 1830–34)

- Further reading

-

- "Therese Huber." In: Wilson, Katharina M. An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers. Vol. 1. Taylor & Francis, 1991. 573-4.

- Blackwell, Jeannine. "Marriage by the Book: Matrimony, Divorce, and Single Life in Therese Huber's Life and Works." In: In the Shadow of Olympus: German Women Writers Around 1800. Eds. Katherine Goodman and Edith Waldstein. Albany: SUNY Press, 1992. 137-156.

La Roche, Sophie von (1730–1807)

Source: Wikipedia

- Primary

-

- Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim. Von einer Freundin derselben aus Original-Papieren und andern zuverläßigen Quellen gezogen (Leipzig, 1771)

- Der Eigensinn der Liebe und Freundschaft, eine Englische Erzählung, nebst einer kleinen deutschen Liebesgeschichte, aus dem Französischen (Zürich, 1772)

- Rosaliens Briefe an ihre Freundin Mariane von St** (Altenburg, 1780-81)

- Pomona für Teutschlands Töchter (Speier, 1783-84)

- Moralische Erzählungen: Pomona für Teutschlands Töchter (Spier, 1783/4)

- Briefe an Lina, ein Buch für junge Frauenzimmer, die ihr Herz und ihren Verstand bilden wollen (Leipzig 1788)

- Neuere moralische Erzählungen (Altenburg, 1786)

- Tagebuch einer Reise durch die Schweiz (Altenburg, 1787)

- Journal einer Reise durch Frankreich. (Altenburg, 1787)

- Tagebuch einer Reise durch Holland und England (Offenbach, 1788)

- Geschichte von Miß Lony und Der schöne Bund (Gotha, 1789)

- Briefe über Mannheim (Zürich, 1791)

- Rosalie und Cleberg auf dem Lande (Offenbach, 1791)

- Erinnerungen aus meiner dritten Schweizerreise (Offenbach, 1793)

- Briefe an Lina als Mutter (Leipzig, 1795-97)

- Erster Band

- Schönes Bild der Resignation, eine Erzählung (Leipzig, 1795-97)

- Erscheinungen am See Oneida, mit Kupfern (Leipzig, 1798)

- Moralische Erzählungen (Mannheim, 1799)

- Zweite verbesserte und vermehrte Auflage, 1799

- Mein Schreibetisch (Leipzig, 1799)

- Reise vom Offenbach nach Weimar und Schönebeck im Jahr 1799 (Leipzig, 1800)

- Fanny und Julia, oder die Freundinnen (Leipzig, 1801/2)

- Liebe-Hütten (Leipzig, 1803/4)

- Herbsttage (Halle, 1806)

- Melusinens Sommerabende (Halle, 1806)

- Further reading

-

- Milch, Werner. Sophie La Roche: Die Großmutter der Brentanos. Frankfurt: Societäts-Verlag, 1935.

- Dawson, Ruth P. The Contested Quill: Literature by Women in Germany, 1770-1800. University of Delaware Press, 2002.

- Watt, Helga Schutte. "Memories and Fantasies: Sophie La Roche's Herbsttage." In: Challenging Separate Spheres: Female Bildung in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Germany. Noth American Studies in 19th-Century German Literature, Vol. 40. Ed. Marjanne E. Goozé. Bern: Peter Lang, 2007. 51-72.

Mereau, Sophie (née Schubart) (1770-1806)

Source: Wikipedia

- Primary

-

- Das Blüthenalter der Empfindung (1794)

- Marie (1798)

- Elise (1800)

- Gedichte (Berlin, 1800-1803)

- Amanda und Eduard (1803)

- Flucht nach der Hauptstadt (1806)

- Sapho und Phaon: Ein Roman (Aschaffenburg, 1806)

- Correspondence

-

- Briefe von Friedrich Schiller an Sophie Mereau (1795-1802)

- Friedrich Schiller Archive (friedrich-schiller-archiv.de)

- Letter to Immanuel Kant from Sophie Mereau, December 1795.

- In: Kant, Immanuel. Correspondence. Trans. and ed. Arnulf Zweig, 1999. 503-4.

- Further reading

-

- Besserer Holmgren, Janet. "Sophie Mereau: 'I don't want to live only for the moment...'" In: The Women Writers in Schiller's Horen: Patrons, Petticoats, and the Promotion of Weimar Classicism. University of Delaware Press, 2007.

- Hammerstein, Katharina Von. Sophie Mereau-Brentano: Freiheit-Liebe-Weiblichkeit. Trikolore sozialer und individueller Selbstbestimmung um 1800. Winter Verlag, 1994.

- Hammerstein, Katharina Von & Katrin Horn. Sophie Mereau: Verbindungslinien in Zeit und Raum. Winter Verlag, 2008.

Reimarus, Elise (1735-1805)

- Primary

-

- Albert und Lotte Auf Dem Weg Zu Werthers Grab (1774)

- Reprinted in: Spalding, Almut. Elise Reimarus (1735-1805): The Muse of Hamburg. Königshausen & Neumann, 2005. 502ff.

- Cato (1776?)

- Undated; Reprinted in: Spalding, Almut. Elise Reimarus (1735-1805): The Muse of Hamburg. Königshausen & Neumann, 2005. 398-439.

- Bey dem Grabe des Herrn A[ugust] G[ottfried] S[chwalb], von einer Freundinn in Hamburg (1777)

- In: Hamburgischer Correspondent 28, 15. Februar 1777

- Über Gottfried Schwalbs Tod 9. Februar 1777. (1777)

- Reprinted in: Spalding, Almut. Elise Reimarus (1735-1805): The Muse of Hamburg. Königshausen & Neumann, 2005. 499-500.

- Versuch einer Erläuterung und Vereinfachung der Begriffe vom natürlichen Staatsrecht.

- Reprinted in: Spalding, Almut. Elise Reimarus (1735-1805): The Muse of Hamburg. Königshausen & Neumann, 2005. 504-13.

- An die Frau von N** in B** den 10ten April 1772. (1778)

- In: "Schreiben eines Frauenzimmers an ihre Freundinn, den Unterricht überhaupt betreffend. Nebst einer kleinen Kinderphilosophie." Pädagogische Unterhandlungen. 9. Stück (1778): 800-11 [799-824] ["die Tochter eines Weltweisen"].

- Erster Versuch einer kleinen Kinderphilosophie (1778)

- In: “Schreiben eines Frauenzimmers an ihre Freundinn, den Unterricht überhaupt betreffend. Nebst einer kleinen Kinderphilosophie." 9. Stück (1778): 812-21 [799-824] ["die Tochter eines Weltweisen"].

- Philolaus und Kriton: Ein Gespräch aus dem Griechischen (1780)

- In: Deutsches Museum. 6. Stück (Juni 1780): 547-41.

- Freiheit (Hamburg, 1791)

- Translated

-

- Jean-François Marmontel. Die Freundschaft auf der Probe (1769)

- Reprinted in: Spalding, Almut. Elise Reimarus (1735-1805): The Muse of Hamburg. Königshausen & Neumann, 2005. 367-97.

- Voltaire. Zayre. Ein Trauerspiel in fünf Aufzügen

- Reprinted in: Spalding, Almut. Elise Reimarus (1735-1805): The Muse of Hamburg. Königshausen & Neumann, 2005. 440-98.

- Correspondence

- Further reading

-

- Curtis-Wendlandt, Lisa. "Legality and Morality in the Political Thought of Elise Reimarus and Immanuel Kant." In: Political Ideas of Enlightenment Women: Virtue and Citizenship. Ashgate, 2014.

- Spalding, Almut. Elise Reimarus (1735-1805), The Muse of Hamburg: A Woman of the German Enlightenment. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2005.

- Spalding, Almut. "Elise Reimarus's 'Cato': The Canon of the Enlightenment Revisited." The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. Vol. 102, No. 3 (July 2003). 376-389

- "Women and revolution in Italy, Germany, and Holland." In: Green, Karen. A History of Women's Political Thought in Europe, 1700–1800. Cambridge: Cambrdige, 2014. 235-49.

Rodde-Schlözer, Dorothea von (1770-1825)

Source: Wikipedia

- Further reading

-

- "Schlözer, Dorothea (von Rodde)." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 3. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 1029-30.

Salomon, Adelgunde Konkordie (1726-1789)

- Primary

-

- Neue Erweiterungen der Erkenntnis und des Vergnügens (1753-62)

- Das Pfandspiel, oder artige und aufgeweckte Geschichte: Aus dem Französischen (Frankfurt and Leipzig, 1755)

- Further reading

-

- "Salomon, Adelgunde Konkordie." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 3. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 974.

Schlegel-Schelling, Caroline (1763-1809)

Source: women-in-history.eu

- Correspondence

-

- Caroline: Briefe aus der Frühromantik, ed. Erich Schmidt (Leipzig, 1913)

- Begegnung mit Caroline: Briefe von Caroline Michaelis-Böhmer-Schlegel-Schelling (Leipzig, 1979)

- Further reading

-

- "Schlegel-Schelling, Caroline." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 3. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 1017-8.

- Friedrichsmeyer, Sara. "Carloine Schlegel-Schelling: 'A Good Woman, and no Heroine.'" In: In the Shadow of Olympus: German Women Writers Around 1800. Eds. Katherine Goodman and Edith Waldstein. Albany: SUNY Press, 1992. 115-136.

- Reulecke , Martin. Caroline Schlegel-Schelling. Virtuosin der Freiheit. Eine kommentierte Bibliographie. Wurzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2010.

- Ritchie, Gisela F. Caroline Schlegel-Schelling in Wahrheit und Dichtung. Bonn: Bouvier, 1968.

- Daley, Mary Margaret. Women of Letters: A Study of Self and Genre in the Personal Writing of Caroline Schlegel-Schelling, Rahel Levin Varnhagen, and Bettina von Arnim. Camden House, 1998.

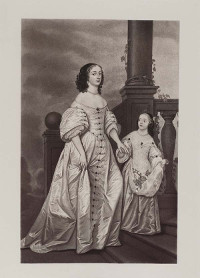

Sophia of Hanover (1630-1714)

Sophia with daughter Sophia Charlotte

Source: Wikipedia

- Correspondence

-

- Strickland, Lloyd (Ed. & trans.). Leibniz and the Two Sophies: Philosophical Correspondence. Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2011.

- Further reading

-

- Zedler, Beatrice H. "The Three Princesses." Hypatia, Vol. 4, No. 1, The History of Women in Philosophy (Spring, 1989). 28-63.

- Strickland, Lloyd. "The Philosophy of Sophie, Electress of Hanover." Hypatia, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Spring, 2009). 186-204.

- Sophie (Sophia) (1630-1714)

Sophia Charlotte of Hanover (1668-1705)

Source: Wikipedia

- Correspondence

-

- Strickland, Lloyd (Ed. & trans.). Leibniz and the Two Sophies: Philosophical Correspondence. Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2011.

- Further reading

-

- Zedler, Beatrice H. "The Three Princesses." Hypatia, Vol. 4, No. 1, The History of Women in Philosophy (Spring, 1989). 28-63.

- "From Hanover and Leipzig to Russia." In: Green, Karen. A History of Women's Political Thought in Europe, 1700–1800. Cambridge: Cambrdige, 2014. 102-130.

- Sophie (Sophia) Charlotte (1668-1705)

- Sophie Charlotte Königin in Preußen

Unzer, Johanna Charlotte (1724-1782)

Source: Wikipedia

- Primary

- Correspondence

-

- Briefe von Dorothea Schlegel an Friedrich Schleiermacher (Berlin, 1913)

- Caroline und Dorothea Schlegel in Briefen, ed. Ernst Wienecke (Weimar, 1914)

- Briefe von und an Friedrich und Dorothea Schlegel, Kritische Friedrich Schlegel-Ausgabe, ed. Ernst Behler, vol. 23 (Paderborn, 1987)

- Further reading

-

- "Unzer, Johanna Charlotte." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 3. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 1210-1.

Veit-Schlegel, Dorothea (1765-1839)

Source: Wikipedia

- Primary

-

- Florentin: ein Roman (1801)

- Geschichte des Zauberers Merlin (1804)

- Further reading

-

- "Veit-Schlegel, Dorothea." In: The Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Vol. 3. Eds. Heiner F. Klemme and Manfred Kuehn. Continuum, 2010. 1214-5.