Introduction to Apoptosis

& Efferocytosis

Apoptosis,

the controlled demolition of old, unneeded, infected or damaged cells,

is fundamental to homeostasis and immunity. Each day billions of cells

in our body undergo apoptosis, wherein the cellular contents of dying

cells are degraded and packaged into membrane bound vesicles termed

apoptotic bodies. Apoptotic bodies serve a dual purpose: they prevent

the spillage of cellular contents into the extracellular milieu, while

simultaneously packaging cell contents into particles small enough to

be internalized by professional phagocytes.

The clearance of apoptotic bodies by

phagocytes – termed efferocytosis

– is required for tissue homeostasis, with failure to clear these

particles leading to inflammation, autoimmunity and neurodegenerative

diseases. If not cleared promptly, apoptotic bodies rupture and release

their contents in a process termed secondary necrosis. Because these

intracellular contents include pro-inflammatory substances such as

nucleotides (ATP, UTP), secondary necrosis promotes inflammation.

Indeed, the defective removal of apoptotic cells is an initiating event

in inflammatory disorders such as atherosclerosis.

While it is unclear if secondary necrosis drives autoimmunity,

it is well established that the presentation of antigens derived from

apoptotic cells plays a central role in maintaining self-tolerance,

with failures in this system leading to autoimmunity. The regulation of

apoptosis and the subsequent clearance of apoptotic cells also

contributes to immunity against infectious agents such as viruses and

intracellular bacteria. Efferocytosis of apoptotic bodies released by

infected cells allows for the processing and presentation of

intracellular pathogen-derived antigens by professional phagocytes.

These phagocytes then transport these normally sequestered antigens to

lymphatic tissues, where the antigens are the presented on MHC II, thus

driving the formation of adaptive immunity.

Despite the obvious importance of efferocytosis, little is known about the process itself. Efferocytosis is a three step process, consisting of an initial recognition of the apoptotic body, internalization of the apoptotic body by a phagocyte, and finally, destruction of the apoptotic body. Research in the Heit lab focuses on the signalling which regulates these processes, with a focus on the receptors that bind apoptotic bodies and the signalling these receptors induce.

Efferocytosis

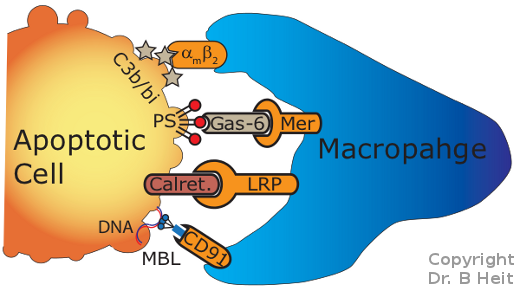

Efferocytosis occurs when receptors on

phagocytes

such as macrophages recognize "eat me" signals displayed by

dying (apoptotic) cells (Figure 1). These

eat-me signals are recognized by specialized receptors on the

macrophage. When engaged, these receptors induce a signaling

pathway which controls the consumption of the apoptotic cell by the

phagocyte.

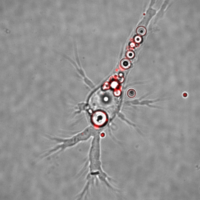

Following the uptake of the apoptotic

body, it must be degraded by the phagocyte (Figure 2).

It is thought that this process occurs through the same phagocytic

mechanism used by phagocytes to destroy bacteria and other

pathogens. However, evidence developed in our lab suggests that

this is not the case, and instead, a unique degradative pathway appears

to be involved.

Failures in the efferocytic process appears to underly many human diseases. Inappropriate processing of apoptotic cells may cause the phagocyte to display antigens derived form the apoptotic cell to the immune system. This inappropriate presentation of self-antigens leads to autoimmune diseases such as lupus, multiple sclerosis and type I diabetes. By understanding the normal processing verses abnormal processing of apoptotic-cell derived antigens, we hope to find new therapies to reverse or prevent autoimmune diseases.

Efferocytic

failures also appear to occur during

atherosclerosis,

which leads to heart

attacks and stroke.

It is normal for the cells in our hearts to take up "bad"

cholesterol. This stresses the cells, leading them to die via

apoptosis. Normally these dead cells are cleared by

efferocytosis, but in some individuals these apoptotic cells are not

removed, leading to the accumulation of dead and dying cells beneath

the blood vessels of the heart. This accumulation is termed an

atheroma

or atherosclerotic plaque, and if this atheroma grows too large it

can rupture, leading to blood clots. If these clots lodge in

the heart or brain, the patient will respectively experience an

ischemic stroke or heart attack. By determining why the

efferocytic process fails in atherosclerotic patients we may be able

to find ways to reverse or prevent atherosclerosis.

Phagocyte Membrane Biology

The plasma membrane

is the sole barrier separating the cellular machinery from the

extracellular environment. This imbues the plasma membrane with

critical roles in modulating signal transduction, transport and

secretion. In efferocytois, the plasma membrane acts as both the

surface that contains the efferocytic receptors, and is the surface of

the apoptotic cell recognized by these receptors. Its long been

thought that the plasma membrane was comprised of a "sea" of lipids in

which proteins floated freely. Recent evidence has shattered

these assumptions, demonstrating that cellular membranes are segmented

such that most proteins in the membrane are confined to small regions

(80-200 nm) of the membrane termed corrals. Furthermore, the liquid

portion of the plasma membrane is divided into numerous microdomains –

small (<100 nm) "islands" in which specific membrane lipids and

proteins are concentrated.

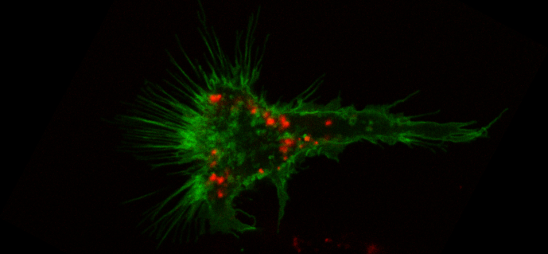

Microdomain "Islands": The number, type and size of microdomain "islands" is unknown, but at a minimum four types exist - lipid rafts, tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs), protein-stabilized microdomains (PSMs) and glycosphingolipid- enriched microdomains (GEMs). The role of these microdomains is unknown, but we hypothesize

that these islands act to assemble the receptors which recognize

apoptotic cells into preformed complexes along with their signaling

molceules and co-receptors. This enhances the function of

efferocytic receptors by ensuring they remain associated with the

machinery which allows them to work, while at the same time preventing

accidental triggering of the receptors by segregating them into

complexes which are too small on their own to signal. Upon

engaging an apoptotic cell these domains would cluster, activating the

receptors.

Corrals: Further complicating the substructure of the plasma membrane are corrals – “fences” of an unknown composition that partitions the plasma membrane into numerous sub-regions. Within corrals membrane proteins diffuse freely, but escape from corrals is limited. It is not clear what forms these corrals, but it is thought that areas of low cytoskeleton density below the membrane may create these corrals, with the barriers between corrals comprised of higher density cytoskeleton. We believe these corrals serve two very important purposes - firstly, we hypothesize that corrals act to prevent spontaneous signaling through phagocytic receptors by limiting the ability of membrane proteins to spontaneously coalesce. Secondly, we hypothesize that interactions between these corrals and membrane proteins are required for phagocytes to generate forces, such as those required to internalize an apoptotic cell.

Research in the Heit lab addresses these three hypotheses, using phagocytes and apoptotic cells as a model system. Importantly, clinically relevant factors such as hypercholesterolemia

can alter the structure and formation of microdomains and corrals,

suggesting that atherosclerosis-associated efferocytic defects may stem

directly from membrane defects caused by excess cholesterol.

Also from this web page: